What Exactly is Iron Ore?

The industrial era and the power of steel have vastly shaped our societies today. Iron ore is a big part of that. Maybe you’re learning about the history of the region where you live. Perhaps you come from a family of miners.

It’s possible that you only know “iron ore” from a Settlers of Catan playing card (a great winter-time board game). But what the heck even is iron ore? That’s a fair thing to be curious about. Keep reading and find out.

So What The Heck Is Iron Ore?

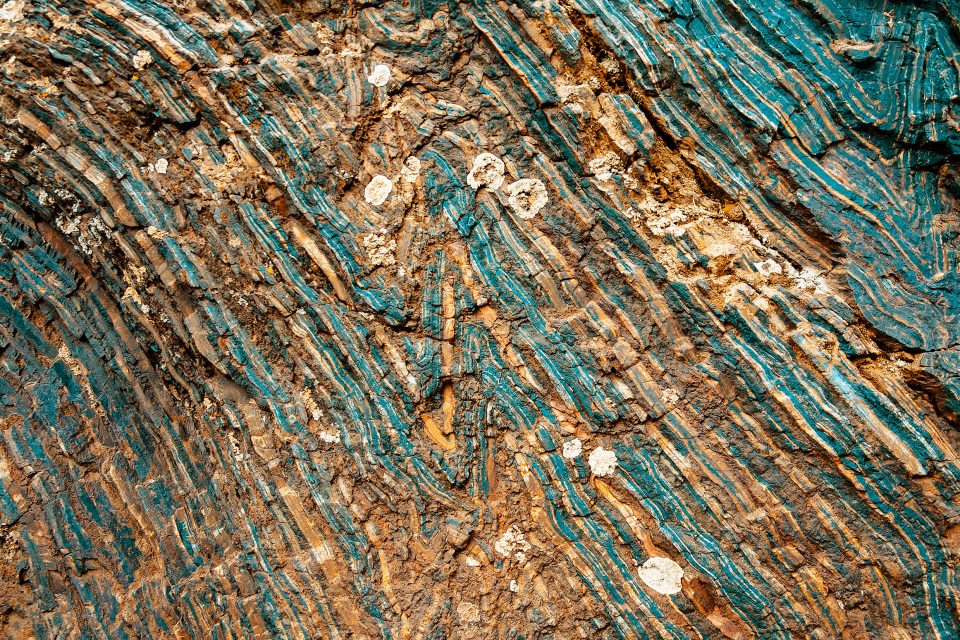

Iron ore, or iron ores, are types of rock and minerals from which we can extract metallic iron. These rocks and minerals vary in color, ranging from rusty red, deep purple, a striking yellow, and dark grey.

Iron itself is one of the most abundant elements in the universe that we know of. It’s a mineral that our bodies need for growth and development. It is also responsible for the red color we can often witness in the world around us.

It is especially obvious to see in the landscape in areas of the red rock deserts of Utah and the deep red sands of Western Australia.

There are four main types of iron ore deposits:

Massive hematite

Hematite (Fe2O3) itself is a very common mineral. It can form as a sedimentary precipitate. It forms as other iron-rich minerals weather and through time, space, and oxidization.

Magnetite

As the name implies, this is a magnetic mineral. Made up of iron oxide, we have found it in igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rock. The imperial formula is Fe3O4. We historically called this mineral ferrous–ferric oxide and triiron tetraoxide.

Titanomagnetite

This is a mineral containing titanium and iron. The mineral sometimes forms as “iron sands”. There are extensive deposits of this along the west coast and North Island of New Zealand.

Pisolitic ironstone

Pisolitic ironstone is another mineral, made up of hematite, chamosite (silica or silicates), siderite, magnetite, and goethite or limonite. In the middle Niger Valley of Nigeria, for example, two principal levels of this ironstone are separated by a bed of argillaceous sediment.

Where The Heck Is It?

We’ve touched on iron ore’s presence in New Zealand and Nigeria already, but Iron ore makes up 5% of the Earth’s crust and is distributed all around the planet.

For instance, a mining and resource extraction company called BHP boasts 5 mines in the Pilbara region of Western Australia, though Rio Tinto is the largest mining company in this region. Australian exports make up half of the world’s iron ore.

Brazil is another heavy hitter, exporting about 23% of the world’s iron ore. As is no surprise to anyone paying attention, mining can be an excessively detrimental activity in ecosystems. This is very true in the case of the Amazon forest. Indigenous activists and global environmentalists are working to mitigate and interrupt this destruction – though the global appetite for steel shows no signs of slowing down.

And while these two countries are the largest producers and control the largest iron ore resource reserves, the whole globe is truly in on the action.

Russia, China, and Ukraine follow Australia and Brazil to total reserves and industry output. Other countries like South Africa and the United States do maintain iron ore reserves.

And while it is a smaller percentage of the global scale, the mining industries play big roles in governmental policy and public opinion campaigns.

How In The Heck Is Iron Ore Used?

So how in the heck is iron ore used after humans extract it from these places? The vast and diverse forms it takes in our lives can be a bewildering reality to ponder.

We use steel (made from iron ore) more than 20 times the amount of any other metals combined. It takes around 1.6 tons of iron ore to produce one ton of steel.

Once iron ore is mined and extracted from the Earth’s crust, we smelt it into steel – then import it or export it to buyers. These buyers (private companies and nation-states alike) then use it to make a wide variety of products that we use every day.

For example, iron ore is used in major construction projects for buildings and bridges. It is used in household appliances such as toasters, refrigerators, and ovens. It is a major component of most of our modes of transport: planes, trains, trucks, buses. It’s in the space ships we send to the moon and in the rockets we launch across borders.

Iron ore is also an important aspect of renewable energy enterprises – making up wind turbines and electricity pylons. It is a strange iron-y (get it?) that our most touted methods of sustainable energy depend on resource extraction and emission-heavy industries. This is surely one of the great challenges of our global community, yet to be decided for the future to come.

How The Heck Does Iron Ore Become Steel?

Noticing steel all around you can certainly lead to ever-expanding and existentialist abstract thoughts – but let’s narrow our focus back down to the actual process at hand.

How the heck do raw materials – iron-infused sediment in the earth’s crust – become the backbone of our city skyscrapers? What are the processes behind steel and steelmaking?

Here’s the gist: iron ore is mined, then transported to specific facilities. People (with the help of machines, made of steel of course) then mix the iron ore with “coke” in a blast furnace. The coke comes from super-heated metallurgical coal.

Heated air blasts into the furnace and creates a 2,000 temperature flame. The heat converts the ore into molten “pig iron” and slag – a refining step in the process but not the final product.

People (and their machines) then remove impurities from the pig iron and slag, while other alloying elements are added. This is the part of the process where steel emerges. We then cast, cool, and roll the steel for use in future projects.

This process of heating, melting, and extracting metal from ore is called smelting. And while it is a highly industrialized business today, smelting is also an artform burned into legends and folklore around the globe.

Blacksmiths and alchemists overlap throughout our history in a delightful play between efficiency-focused technology, and the fantastical, whimsical endeavors to create magic and brew gold. Some of the western world’s most revered scientists – Newton, Galileo, and others, were believers in this combined power of iron ore, working and experimenting in both the practical and mystical realms.

What The Heck Is Going On With Iron Ore Today?

Today, China dominates steel production and the steel industry – mining, processing, importing, and transporting over 43% of the world’s pig iron production and 35% of global production. That’s one heck of a lot of iron ore exports – and China certainly has the emissions to back it up.

But there are plenty of countries – and big mining companies – playing a role in the destruction of biodiversity and critical ecosystems in the name of extract iron ore from the ground. The company Vale, in Brazil, has an annual revenue of $32 billion – and that is just one company sitting on a 3,000 square mile tract of forest.

Companies such as Vale have tentatively begun to collaborate with conservationists – but only after deadly mining disasters, explosive exposes, and global condemnation and divestment.

The iron ore price is at record highs as of June 2021, raising up to $233.10 USD per metric ton. And countries are buying tonnes and tonnes as they inject resources and infrastructure plans into their economies as a way to bounce back after the global pandemic.

Conclusion

In understanding a bit about iron ore, we are aware of how the industry impacts us. We can see how it determines aspects of life on earth. People can demand that community leaders, national representatives, and global coalitions protect the planet from detrimental mining practices.

We can also protect and preserve the rights and human dignity of iron ore miners. Iron ore production isn’t going anywhere anytime soon from the looks of it. This is why we have to figure out how to regulate and minimize the destruction of the current process.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.