How Many Satellites in Space Do We Know About?

If you look up at the sky on any clear night, you are sure to spot a man-made satellite. These devices crisscross the part of earth’s atmosphere called low-earth orbit (LEO). They provide essential services for GPS, telecommunications, images of Earth’s surface, and much more. Seeing all these makes you wonder, how many satellites are there in space that we know about? The Union of Concerned Scientists tracks all available information about satellites in space. They currently list 2,062 satellites orbiting the earth.

A Brief History of Satellites

What Is a Satellite?

Though this may seem like a silly question, the answer may surprise you. Though we generally think of satellites as only the pieces of man-made technology that enable us to access Dish TV and use Google Maps, ‘satellite’ is actually a far more general term. Any object orbiting a planet or a star is technically a satellite. In this article, we will be focusing on artificial satellites.

The First Artificial Satellites

A Replica of Sputnik

Sputnik made history on October 4, 1957, as the first artificial satellite to orbit the earth. Launched by the Soviet Union, this beachball sized hunk of metal ignited the space race. This technological arms race between the USA and the USSR lasted for decades. Though it was the result of the political tensions of the cold war, it resulted in the creation of many technologies that have become essential to daily life.

Satellites do Everything

The ability to launch artificial satellites into space has allowed humanity to do many amazing things. From viewing high-resolution imagery of the entire surface of our planet, to pinpointing your location from a handheld device, we use satellites constantly.

Satellites are used for many things. Beyond the many consumer applications of satellites, governments also rely on these devices. Military communications, intelligence collection and much more is enabled by satellites. These classified satellites are shrouded in secrecy. Some adventurous amateur astronomers track and monitor these secret satellites. There are hundreds of these secret satellites orbiting our planet.

Conservation efforts also benefit greatly from satellite data. Satellites are used to monitor bird migrations, track forest fires, stop illegal fishing and much more. Satellites are also essential to track global warming through sea level data, temperature trends, and carbon storage.

More Satellites Than Ever

Many companies and governments deploy satellites. As tech improves, satellites are getting cheaper and cheaper. Tiny “CubeSats” can be built for as little as $25,000. Though launching these satellites still costs millions, the barrier to getting an object into space is continually dropping. This means that more satellites than ever are going into space.

With so many satellites in space, crashes with space junk and other satellites are a growing problem. The “Kessler Syndrome” is a prediction about the eventual consequences of all these objects. As more satellites become junk, their risk of colliding and creating more junk increases. This could eventually lead to a domino effect, making low-earth-orbit too congested for satellites. Read more about this phenomenon in our article about the Kessler Syndrome.

The Who’s Who of Satellites

The thousands of satellites in orbit around our planet come from many different sources. Both governments and companies own and operate satellites. As the space industry begins to move further towards private industry, so do the satellites in space. These satellites are constantly growing in number. The Union of Concerned Scientists has taken it upon themselves to do the important work of cataloging all of the satellites in space.

Understanding the origins, paths, and eventual fates of the thousands of satellites in space is important. Though satellites generally enter the atmosphere and burn up, as the number of satellites grows, so do the risks. More companies and governments than ever are launching satellites. Though the USA has the most satellites by far, many small countries have satellites.

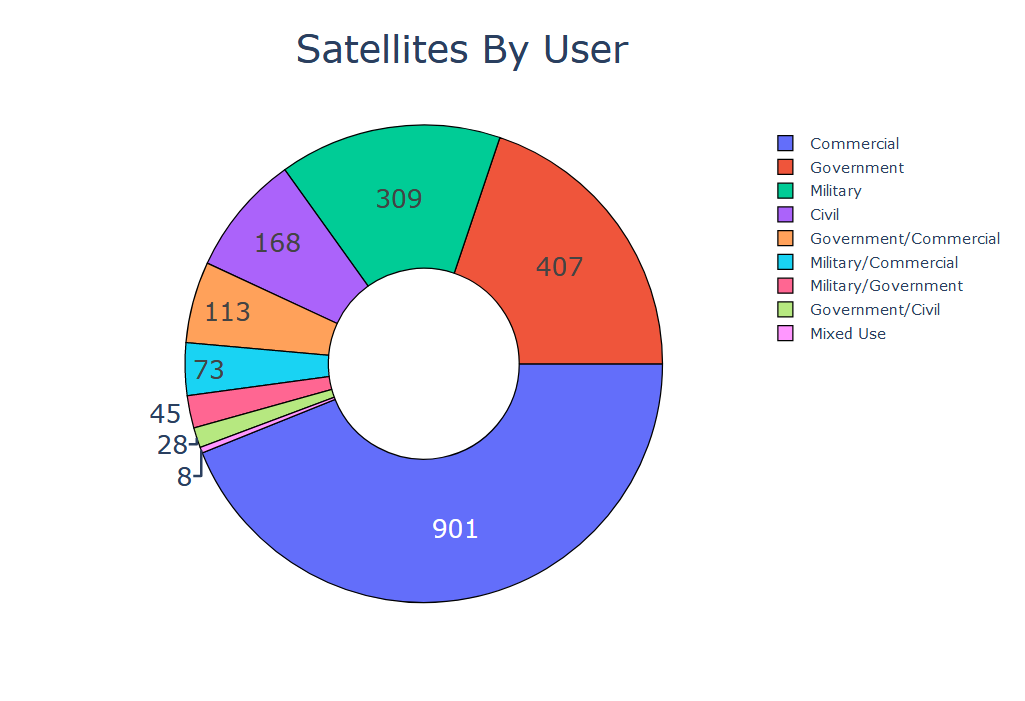

Take a look at these charts for more information about the satellites in space. They were created from the Union of Concerned Scientist’s dataset using Python Pandas and Plotly. Click on the images for an interactive version.

Countries with More Than 10 Satellites

Satellites By Purpose

Satellites By User