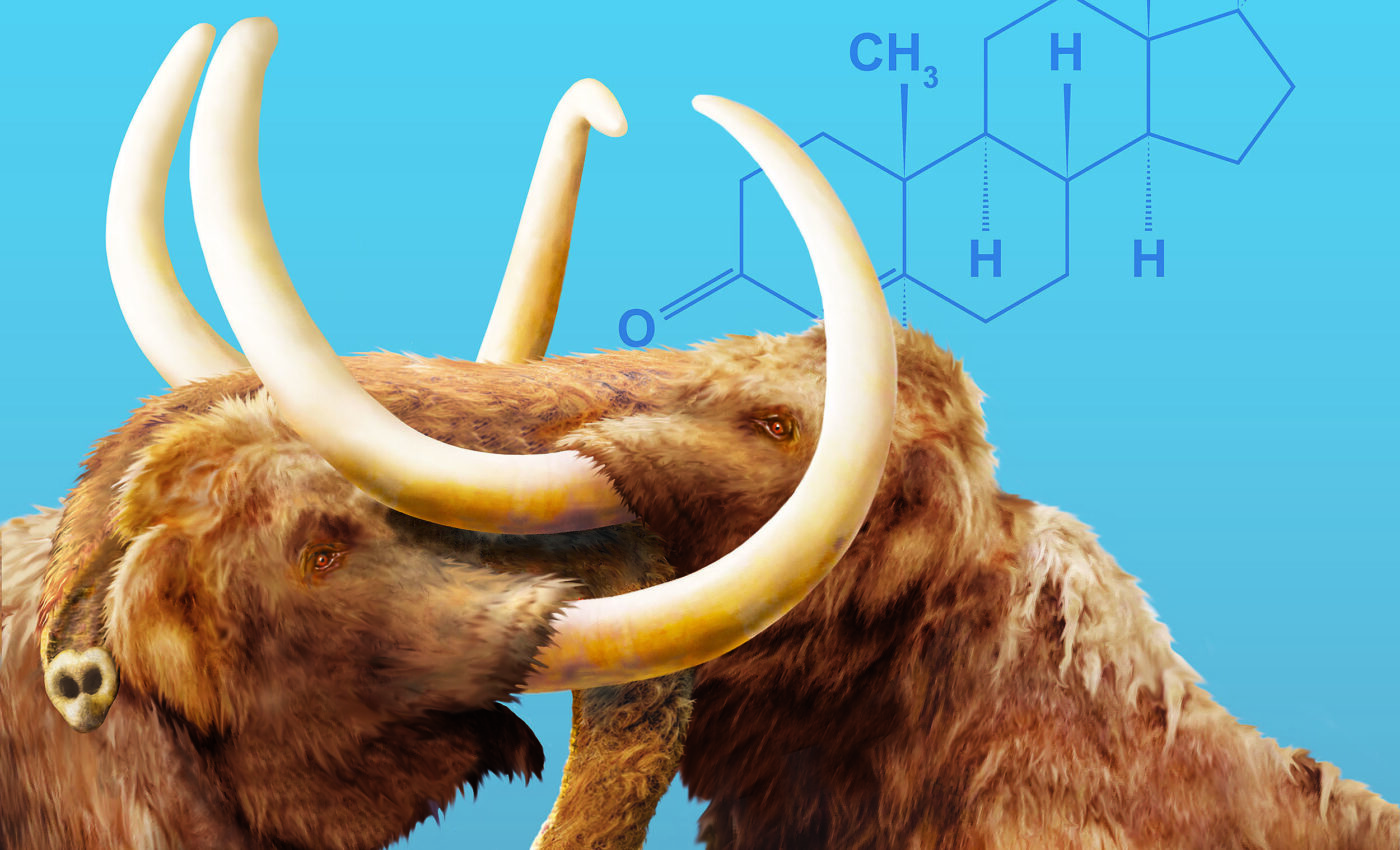

Woolly mammoths had testosterone-driven aggression during mating season

Scientists at the University of Michigan have discovered the first direct evidence of musth, a testosterone-driven episode of heightened aggression against rival males, in adult male woolly mammoths.

The findings, based on traces of sex hormones extracted from a woolly mammoth’s tusk, reveal that the extinct species experienced musth in a manner similar to modern elephants.

While elevated testosterone levels during musth in male elephants had previously been detected through blood and urine tests, musth battles in extinct relatives of modern elephants were only inferred from indirect evidence such as skeletal injuries and broken tusk tips.

However, this new study, published online in the journal Nature, is the first to demonstrate that testosterone levels are recorded in the growth layers of both mammoth and elephant tusks.

What the scientists learned

The researchers, in collaboration with their international colleagues, reported annually recurring testosterone surges up to ten times higher than baseline levels within a permafrost-preserved woolly mammoth tusk from Siberia.

The adult male mammoth in question lived more than 33,000 years ago. The study authors also found that the testosterone surges seen in the mammoth tusk are consistent with musth-related testosterone peaks observed in an African bull elephant tusk.

“Temporal patterns of testosterone preserved in fossil tusks show that, like modern elephants, mature bull mammoths experienced musth,” said study lead author Michael Cherney, a research affiliate at the U-M Museum of Paleontology and a research fellow at the U-M Medical School.

The research establishes that both modern and ancient tusks hold traces of testosterone and other steroid hormones. These compounds are incorporated into dentin, the mineralized tissue that constitutes the interior portion of all teeth. Tusks are, in fact, elongated upper incisor teeth.

“This study establishes dentin as a useful repository for some hormones and sets the stage for further advances in the developing field of paleoendocrinology,” Cherney said. “In addition to broad applications in zoology and paleontology, tooth-hormone records could support medical, forensic, and archaeological studies.”

Examining ancient hormones from tusk samples

Hormones, which are signaling molecules that help regulate physiology and behavior, have previously been analyzed in human and animal hair, nails, bones, and teeth in both modern and ancient contexts. However, the significance and value of such hormone records have been subject to ongoing scrutiny and debate.

The authors of the new Nature study believe that their findings should help change this perception by demonstrating that steroid records in teeth can provide meaningful biological information that sometimes persists for thousands of years.

“Tusks hold particular promise for reconstructing aspects of mammoth life history because they preserve a record of growth in layers of dentin that form throughout an individual’s life,” explained study co-author Daniel Fisher, a curator at the U-M Museum of Paleontology and professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences.

“Because musth is associated with dramatically elevated testosterone in modern elephants, it provides a starting point for assessing the feasibility of using hormones preserved in tusk growth records to investigate temporal changes in endocrine physiology,” added Fisher.

How the study was done

The research team developed innovative methods to extract steroids from tusk dentin, which has enabled them to investigate the hormone levels of adult African bull elephants and two adult woolly mammoths from Siberia—one male and one female. The samples were obtained in accordance with relevant laws and appropriate permits.

This groundbreaking research not only offers valuable insights into the hormone levels of these ancient animals but also has potential applications in various fields, including reproductive ecology, life history, population dynamics, disease, and behavior in both modern and prehistoric contexts.

The researchers used CT scans to identify annual growth increments within the tusks. A tiny drill bit, operated under a microscope and moved across a block of dentin using computer-actuated stepper motors, was employed to grind contiguous half-millimeter-wide samples representing approximately monthly intervals of dentin growth. The powder produced during the milling process was collected and chemically analyzed.

Measuring the hormone levels

To measure the steroids in tusk dentin with a mass spectrometer, U-M endocrinologist and study co-author Professor Rich Auchus developed new methods.

“We had developed steroid mass spectrometry methods for human blood and saliva samples, and we have used them extensively for clinical research studies. But never in a million years did I imagine that we would be using these techniques to explore ‘paleoendocrinology,'” said Professor Auchus.

“We did have to modify the method some, because those tusk powders were the dirtiest samples we ever analyzed. When Mike (Cherney) showed me the data from the elephant tusks, I was flabbergasted. Then we saw the same patterns in the mammoth – wow!”

Radiocarbon dating revealed that the male woolly mammoth lived 33,291 to 38,866 years ago, while the female woolly mammoth’s tusk was carbon-dated to between 5,597 and 5,885 years before present.

The researchers found that, as expected, the female woolly mammoth’s tusk showed little variation in testosterone levels over time, and the average testosterone level was lower than the lowest values in the male mammoth’s tusk records.

“With reliable results for some steroids from samples as small as 5 mg of dentin, these methods could be used to investigate records of organisms with smaller teeth, including humans and other hominids,” wrote the study authors.

“This is one of the reasons we come to work every morning at the University of Michigan: to make discoveries that empower us to see the world in new ways,” said study co-author Perrin Selcer of the U-M Department of History. He also emphasized the importance of collaboration across schools and the university’s instrumentation infrastructure.

More about Woolly mammoths

Woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) were large, prehistoric mammals closely related to modern-day elephants. They roamed the Earth during the last ice age, around 400,000 to 4,000 years ago, and were most commonly found in the northern parts of North America, Europe, and Asia.

Physical characteristics

Woolly mammoths were well-adapted to the cold, harsh environments they inhabited. They stood around 9 to 11 feet tall at the shoulder and weighed between 4.5 to 6.8 metric tons. Their most distinctive features were their long, curved tusks, which could grow up to 16 feet in length. These tusks were used for fighting, digging for food, and clearing snow.

Woolly mammoths were covered in a thick, shaggy coat of hair that could be up to 3 feet long, providing insulation against the cold. Underneath the hair was a layer of fat up to 4 inches thick, which helped to conserve heat and store energy. Their large, flat, and furry ears were smaller than those of modern elephants, which helped to reduce heat loss.

Diet

Woolly mammoths were herbivores, primarily feeding on grasses, shrubs, and other vegetation. Due to the cold climate and frozen ground, they used their tusks and trunk to dig through snow and ice to reach plants. The low nutritional value of their diet meant that they had to consume large quantities of food daily.

Social behavior

Woolly mammoths are believed to have lived in social groups, similar to modern elephants. These groups were likely led by a dominant female, or matriarch, and consisted of related females and their offspring. Adult males usually lived apart from the group, either alone or in smaller, loosely associated bachelor groups. Males would join female groups during mating season, engaging in competitive behavior to establish dominance and win mating rights.

Extinction

The exact cause of the woolly mammoth’s extinction remains a subject of debate among scientists. It is widely believed that a combination of factors, including climate change, habitat loss, and overhunting by humans, led to their decline and eventual disappearance. As the Earth warmed at the end of the last ice age, the mammoths’ cold-adapted habitats shrank, and they faced increased competition for resources from other species. Additionally, human populations expanded, and it is thought that overhunting further contributed to the woolly mammoth’s extinction.

Recent discoveries

Thanks to the preserved remains of woolly mammoths found in the permafrost of Siberia and other Arctic regions, scientists have been able to study their DNA and learn more about their biology, behavior, and extinction. These discoveries have also fueled discussions about the possibility of using genetic engineering to “resurrect” the species through de-extinction efforts. However, the ethical and ecological implications of such endeavors remain the subject of ongoing debate.

image Credit: University of Michigan

—-

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.