White dwarf star system is producing mysterious radio signals

Radio astronomers have discovered an unusual phenomenon in recent years. They detected radio pulses from the Milky Way that last from seconds to minutes. These pulses differ from those produced by known radio-emitting neutron stars or pulsars, which typically last only milliseconds.

Unlike conventional radio pulsars, these so-called long-period transients (LPTs) are periodic at timescales of tens of minutes to hours.

Scientists have proposed several theories for the origins of these signals. However, until recently, no solid evidence existed to explain them.

Now, astronomers from the Netherlands and the UK have made a discovery that provides critical insights into these mysterious bursts.

Mysterious star signals in space

In 2022, researchers detected a series of periodic radio signals in space. To investigate the signals, a team of astronomers used an advanced imaging technique with the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR), a powerful international radio telescope.

The research was led by Dr. Iris de Ruiter from The University of Sydney and Dr. Kaustubh Rajwade from University of Oxford.

LOFAR operates like a massive radio camera, capturing detailed images of the sky at low radio frequencies. This telescope allowed the team to pinpoint the exact location of the mysterious radio pulses, which appeared to come from an object about 1,600 light-years away.

To learn more, the scientists conducted follow-up observations using two optical telescopes: the Multiple Mirror Telescope in Arizona and the Hobby-Eberly Telescope in Texas. These observations revealed an unexpected finding.

The signals were not coming from a single star, as initially thought, but from a binary system – two stars orbiting each other. This discovery opened up new possibilities for understanding the source of these unusual radio emissions.

Orbiting stars and strange radio pulses

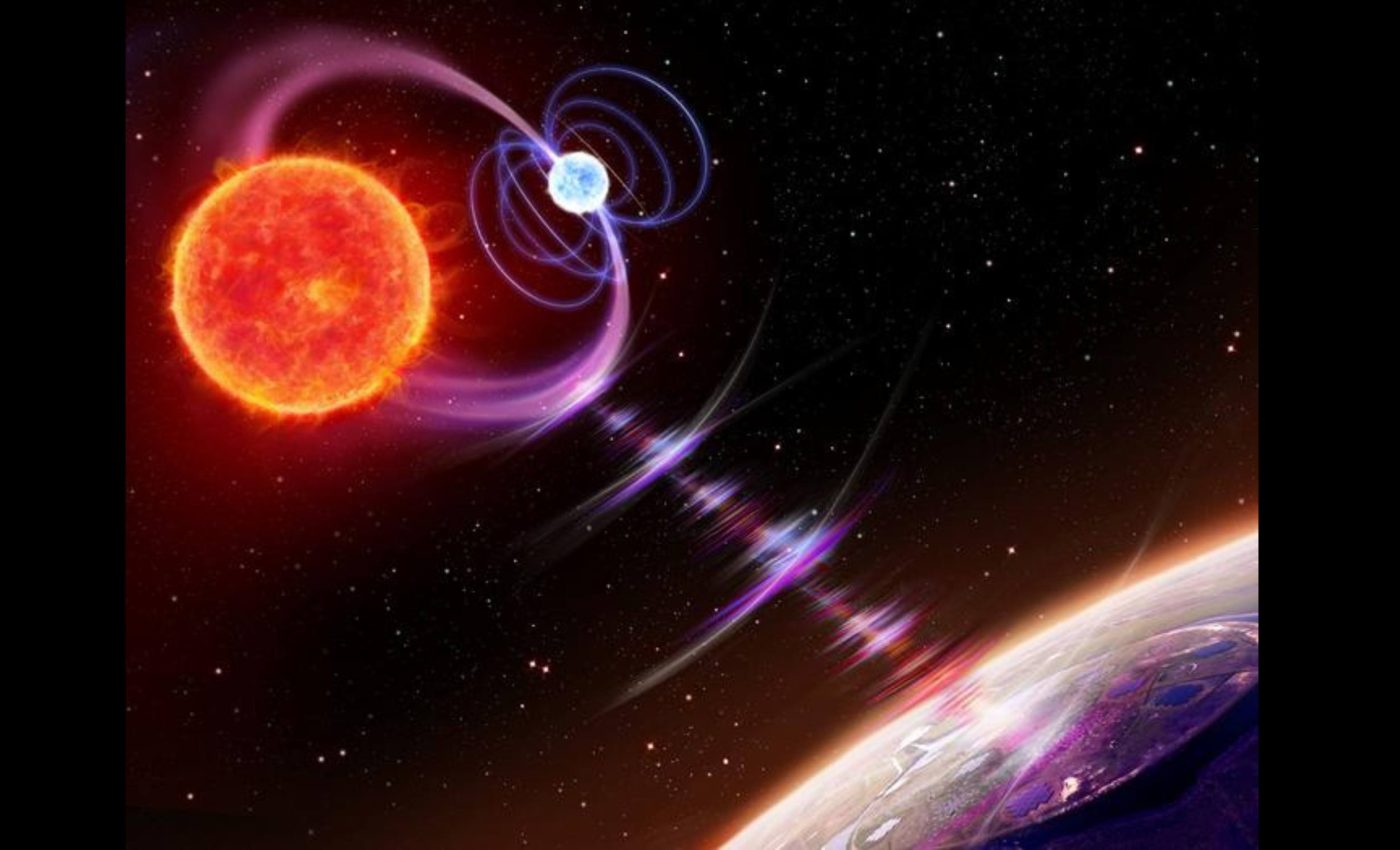

The system consists of two stars orbiting a common center of gravity every 125 minutes.

One is a white dwarf, the remnant core of a Sun-like star that has lost its outer layers. The other is a red dwarf, a small and relatively cool star. This star system lies in the direction of the constellation Ursa Major.

Scientists believe there are two possible explanations for how these stars generate long-lasting radio pulses. The bursts might originate from the intense magnetic field of the white dwarf.

Alternatively, the interaction between the magnetic fields of both stars could be responsible. Additional observations are necessary to determine the exact cause.

Expanding the search for LPTs

“Thanks to this discovery, we now know that compact objects other than neutron stars are capable of producing bright radio emission,” said Dr. Rajwade, who leads the LOFAR-based search for LPTs and helped identify the periodic pattern in these pulses.

“We worked with experts from all kinds of astronomical disciplines,” noted Dr. de Ruiter. “With different techniques and observations, we got a little closer to the solution step by step.”

This discovery is not an isolated case. Over the past few years, astronomers have found about ten similar radio-emitting systems.

However, none of these studies have been able to confirm whether these signals come from a white dwarf or a neutron star. The latest findings bring scientists closer to solving this puzzle.

Searching for more star radio signals

Dr. Rajwade continues to analyze LOFAR data in search of more LPTs.

“This finding is very exciting! We are starting to find a few of these LPTs in our radio data. Each discovery is telling us something new about the extreme astrophysical objects that can create the radio emission we see,” said Dr. Rajwade.

“For instance, the unexpected observation of coherent radio emission from the white dwarf in this study could help probe the evolution of magnetic fields in this type of star.”

As scientists gather more data, they hope to uncover more of these mysterious signals and identify their sources. The study of long-period transients is still in its early stages, but each new discovery adds another piece to the cosmic puzzle.

The findings could lead to a deeper understanding of how stars evolve, how magnetic fields shape the universe, and what other surprises are still waiting to be discovered.

The study is published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Image Credit: Daniëlle Futselaar/artsource.nl

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–