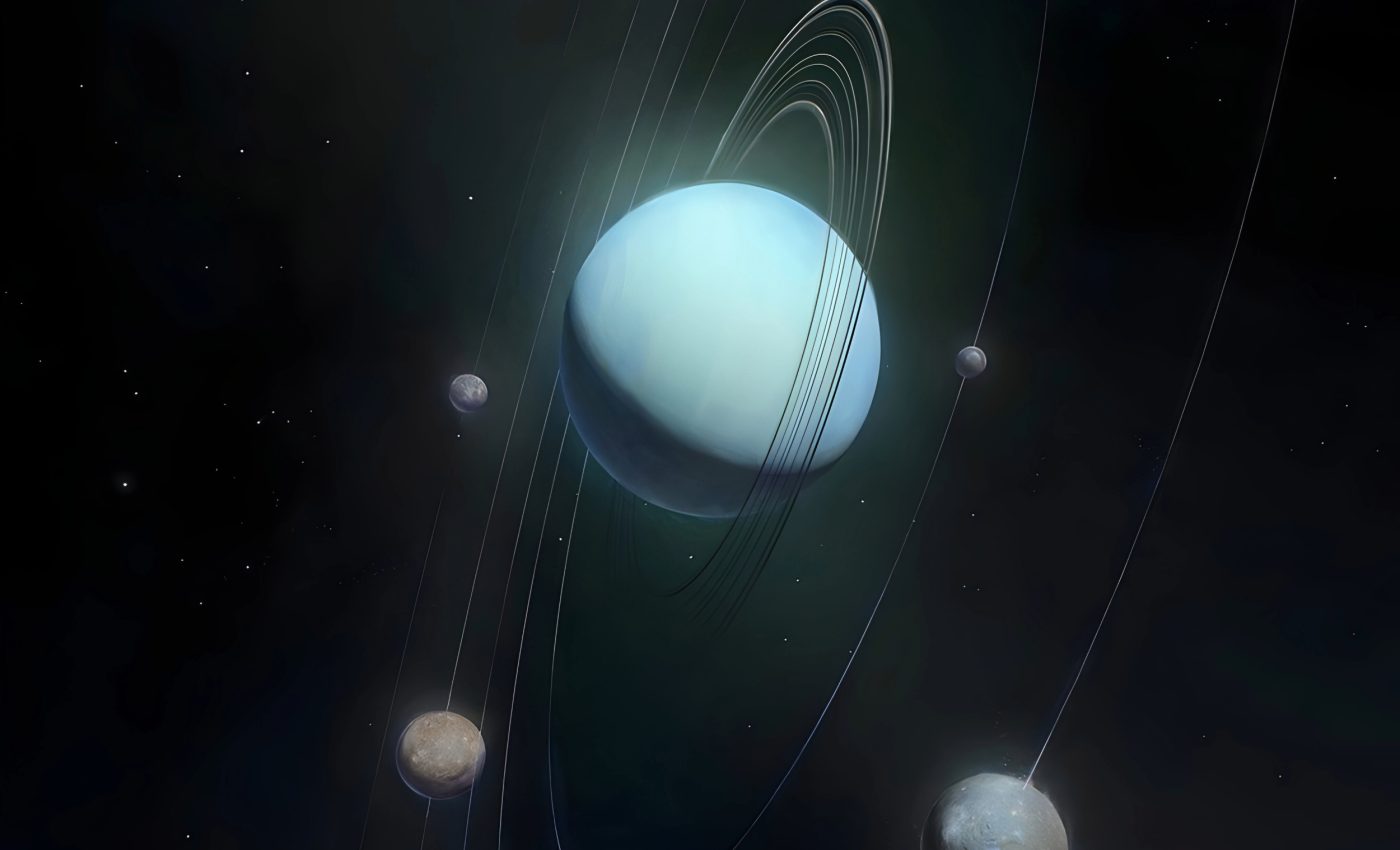

Uranus and its icy moons: Broadening the search for alien life

In 1986, the buzz of NASA’s Voyager 2 enthralled many as it swept past Uranus, capturing images of gargantuan moons blanketed with ice.

As we approach 40 years since that momentous event, NASA is planning to revisit Uranus – this time with an upgraded mission.

Exploring the icy moons

The new mission aims to uncover the secrets beneath the icy cloaks of at least some of the 28 Uranian moons. Scientists also want to establish whether any of the moon’s contain liquid oceans that could potentially support life.

To prepare for this, experts at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG) are crafting a new kind of computer model that will work with the spacecraft’s camera to detect hidden oceans under the moons’ frozen exteriors.

Moons of Uranus: Oscillations and water

The magic lies in the smallest details. Focusing on minuscule oscillations in a moon’s spin as it dances around Uranus, the model can estimate the composition of each moon’s interior – determining whether it contains rock, ice, or water.

Less wobble points towards a solid core of rock or ice, while a pronounced wobble indicates an icy surface floating on an ocean of liquid water.

Paired with gravity data, the model can even calculate the depth of each ocean and the thickness of the ice shrouding it.

Life beyond Earth?

Understanding the watery interiors of the Uranian moons may change how we perceive life as we know it.

“Discovering liquid water oceans inside the moons of Uranus would transform our thinking about the range of possibilities for where life could exist,” explained Doug Hemingway, the UTIG planetary scientist who developed the model.

This pioneering research opens a new avenue for detecting oceans in our external space trips. The findings, published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, promise to enhance the chances of discovery on future missions.

Oscillations and tidal locks

Most of the large moons in our solar system, including those belonging to Uranus, are “tidally locked.” They are gravitationally bound such that the same side always faces the parent planet while in orbit.

But this does not completely restrict the moons; they still sway back and forth as they move around. Understanding the extent of these wobbles will reveal whether Uranus’s moons harbor oceans and their potential sizes.

Detecting oceans on Uranus’s moons

Moons hiding a water ocean within them will oscillate more than those that are rigid all the way through. Take Saturn’s moon, Enceladus, for example. It has an interior global ocean that was confirmed by detecting its slight wobble as it orbits.

The new model developed by Hemingway makes it possible to apply this technique to the moons of Uranus.

If Uranus’s moon Ariel, for instance, wobbles 300 feet, this may suggest the presence of a 100-mile-deep ocean enveloped by a 20-mile-thick shell of ice.

Icy exteriors of distant moons

Determining the presence of oceans in this way requires a spacecraft with powerful cameras. It’s a tricky but potentially rewarding challenge.

However, as Professor Krista Soderlund noted, the new model provides a “slide rule” to understand what will work.

The next step is to augment this model with measurements from other instruments, to enrich our understanding of the moons’ interiors.

Perhaps, in the not too distant a future, we might discover the existence of life beyond our planet, lurking beneath the icy exteriors of distant moons.

Uranus and the search for habitable worlds

The exploration of Uranus and its moons is not just about uncovering their secrets – it’s part of a larger effort to understand habitability in the outer solar system.

The discovery of subsurface oceans on Uranus’s moons could expand the definition of what makes a world potentially habitable.

Unlike rocky planets (such as Earth), these icy moons rely on tidal heating and internal activity rather than solar energy to sustain liquid water.

Such findings would complement discoveries on moons like Europa and Enceladus, potentially suggesting that life could thrive in environments far from a star.

By exploring Uranus’s moons, scientists aim to refine the tools and models necessary to search for life in similarly extreme conditions on exoplanets and their satellites – potentially broadening humanity’s search for extraterrestrial life.

The UTIG research was published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Image Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Mike Yakovlev

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–