Turtle embryos have an ability to avoid extreme temperatures inside the egg

Turtle embryos have an ability to avoid extreme temperatures inside the egg. For some turtle species, the gender of the offspring is largely determined by the temperature of the egg. In a new study, however, experts have discovered that the turtle embryos can move around inside the egg to avoid extreme temperatures. The team set out to investigate how this may benefit the turtles in the face of climate change.

“We previously demonstrated that reptile embryos could move around within their egg for thermoregulation, so we were curious about whether this could affect their sex determination,” said study co-author Professor Wei-Guo Du at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. “We wanted to know if and how this behavior could help buffer the impact of global warming on offspring sex ratios in these species.”

The research team incubated turtle eggs under a range of temperatures in the lab and in outdoor ponds. They found that a single embryo could experience a temperature rise of up of 4.7°C within the egg. This is significant because any shift larger than 2°C can massively change the offspring sex ratio of many turtle species, according to Professor Du.

In half of the eggs, the team applied a chemical that blocked temperature sensors called capsazepine to prevent behavioral thermoregulation.

When the eggs hatched, the researchers found that the embryos without behavioral thermoregulation were either dominantly male or dominantly female, depending on the incubation temperature. Among the embryos that reacted to nest temperatures by moving around inside their eggs, however, about half developed as males and the other half as females.

“The most exciting thing is that a tiny embryo can influence its own sex by moving within the egg,” said Professor Du. By seeking out ideal temperatures, the embryos can shield against extreme thermal conditions and produce a relatively balanced sex ratio.

“This could explain how reptile species with temperature-dependent sex determination have managed to survive previous periods in Earth history when temperatures were far hotter than at present,” said Professor Du.

“The embryo’s control over its own sex may not be enough to protect it from the much more rapid climate change currently being caused by human activities, which is predicted to cause severe female-biased populations. However, the discovery of this surprising level of control in such a tiny organism suggests that in at least some cases, evolution has conferred an ability to deal with such challenges.”

The study is published in the journal Current Biology.

—

By Chrissy Sexton, Earth.com Staff Writer

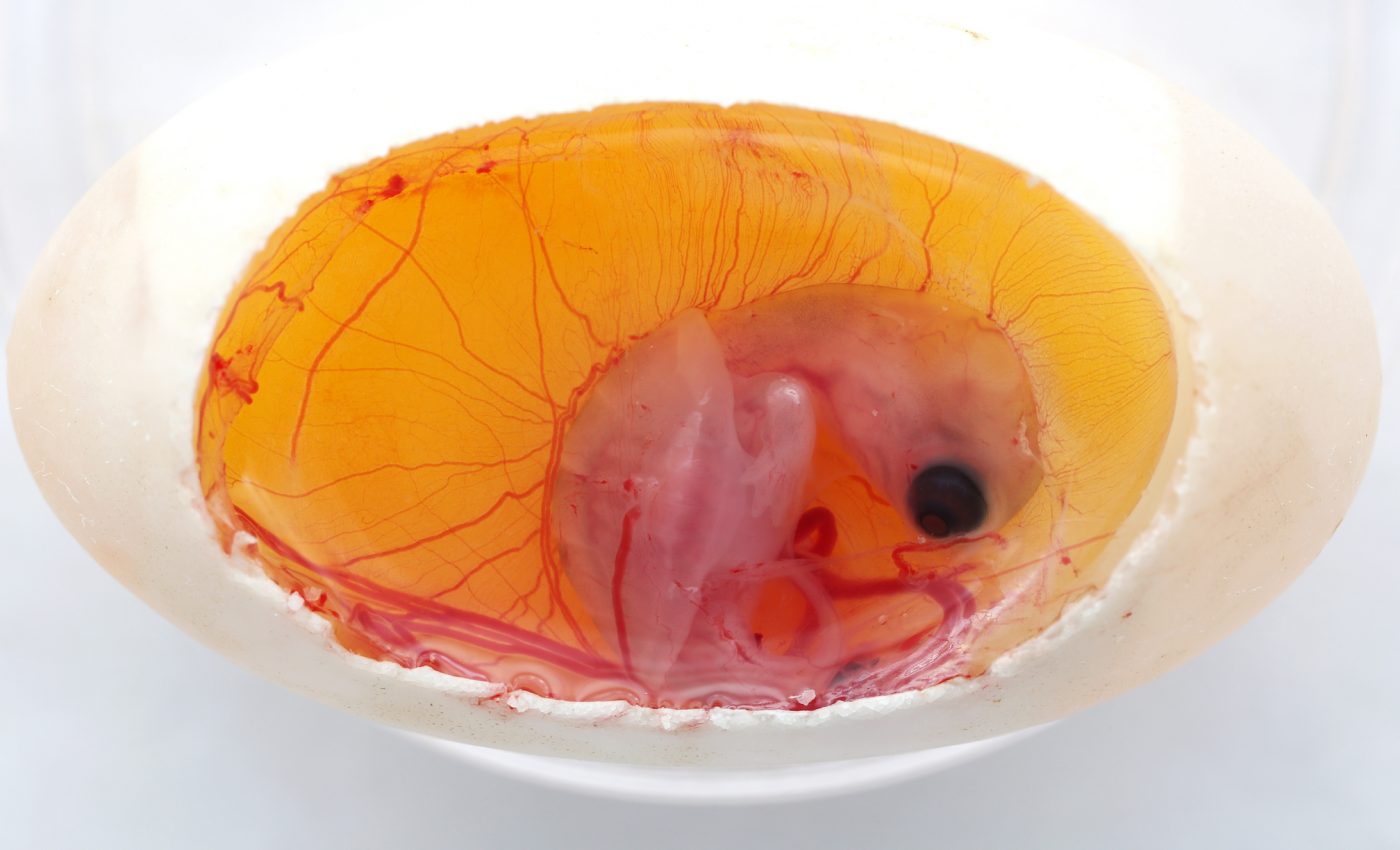

Image Credit: Ye et. al / Current Biology