Sunspot sketches from 1607 unlock secrets of solar activity

In the world of astronomy, the 17th century was marked by significant and groundbreaking discoveries, particularly in the realm of solar activity.

One intriguing contribution was Johannes Kepler’s sketches of sunspots in 1607, a record that laid the foundation for a fresh understanding of solar phenomena.

Observations in sunspot sketches

Johannes Kepler, celebrated for his monumental contributions to astronomy and mathematics, is known to have made one of the earliest instrumental records of solar activity during the early 17th century.

He ingeniously employed a “camera obscura,” an apparatus that projected the sun’s image onto paper, to sketch visible features on the Sun’s surface.

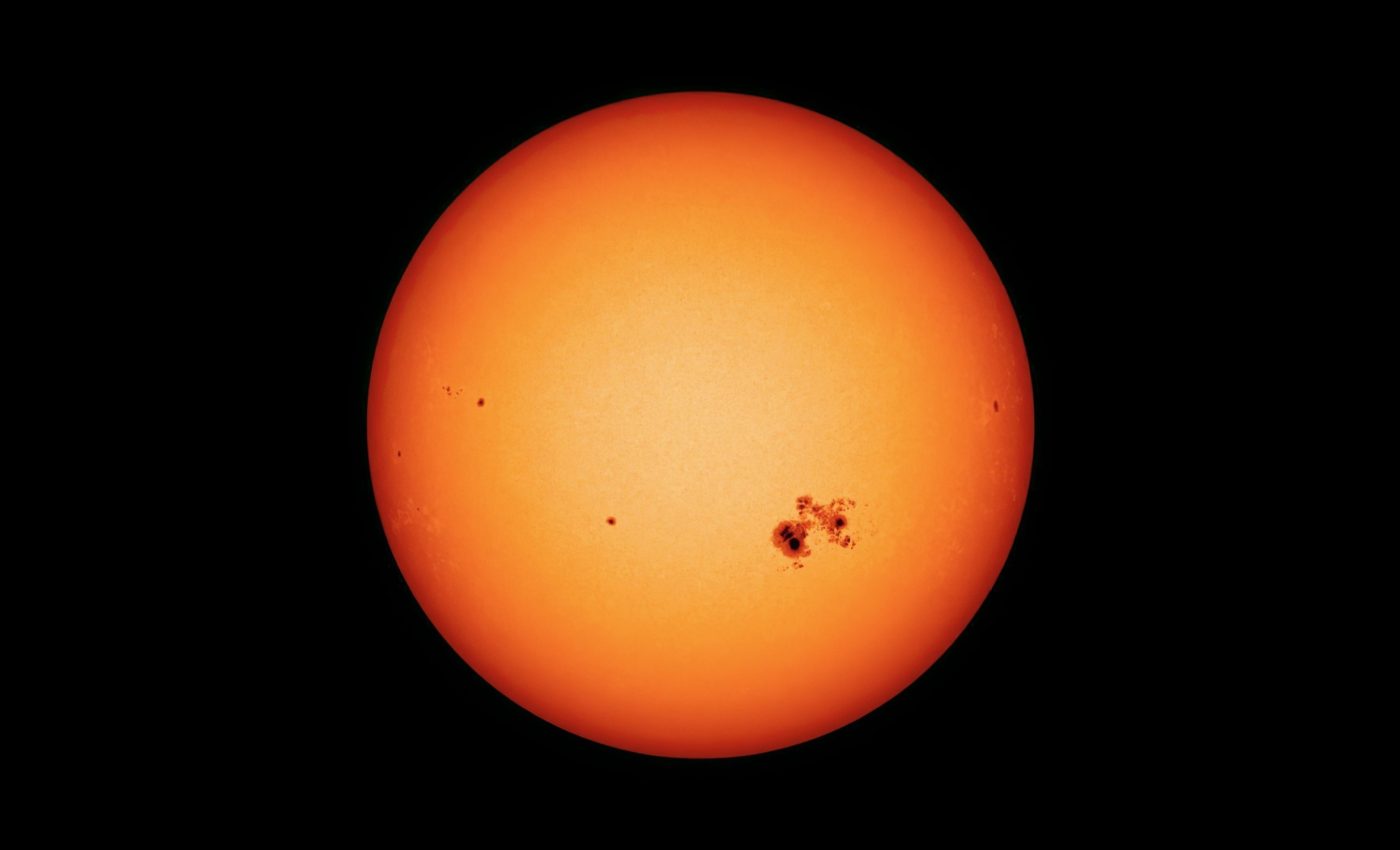

In May of 1607, Kepler documented what he initially misinterpreted as a transit of Mercury across the Sun, later identified as a collection of sunspots. These are darker areas on the sun’s surface that develop due to intense magnetic activity within the sun’s interior.

Sunspots play a key role in solar radiation and space weather. Their occurrence, frequency, and latitudinal distributions appear in cycles, paving the gateway to fresh revelations about solar activity.

Revisiting Kepler’s observations

Led by a collaborative group from Nagoya University in Japan, an international team of researchers revisited Kepler’s eclipsed sunspot sketches with the help of modern techniques.

Using Spörer’s law, they reconstructed the position of Kepler’s sunspot group, situating it at the end of the solar cycle prior to the one observed by notable early telescopic pioneers like Thomas Harriot and Galileo Galilei.

These observations are extremely significant as they shed light on the solar cycles at the start of the 17th century. The cycles during this time mark the transition from regular solar cycles to the grand solar minimum known as the Maunder Minimum (1645–1715).

The grand solar minimum, characterized by an unusually prolonged period of low sunspot activity, holds great importance for researchers to understand solar activity and its effect on the Earth.

Sunspot sketches reveal new insights

By examining Kepler’s records and matching them with contemporary data, alongside modern statistics, the researchers made four pivotal discoveries.

After methodically reinterpreting the sunspot sketches, they located Kepler’s sunspot group at a low heliographic latitude. This pointed to an inconsistency between Kepler’s original text and the two camera obscura images, which display the sunspot towards the upper left of the solar disk.

Using Spörer’s law and modern sunspot statistics, the researchers determined that the sunspot group was positioned at the end of solar cycle -13 instead of the beginning of solar cycle -14.

This finding contradicted with later telescopic observations that showed sunspots at higher latitudes, indicating a typical progression from the preceding solar cycle to the following one in accordance with Spörer’s law.

The researchers also succeeded in estimating the transition between the previous solar cycle (-14) and the next solar cycle (-13) between 1607 and 1610. Kepler’s records proposed a regular duration for solar cycle-13, contesting alternate reconstructions that proposed an extremely long cycle during this period.

The legacy of Kepler

Kepler’s contribution extends beyond observational expertise. His findings provide valuable context that helps to clarify changes in solar behavior during a critical period when solar cycles transitioned to the grand solar minimum.

Kepler’s records, which predate the existing telescopic sunspot records from 1610 by several years, stand as a testament to his scientific prowess. They continue to serve the scientific community today, extending the reach of his legacy into the present.

The future of solar research

As we continue to advance in solar research, the lessons learned from Kepler’s pioneering work are more relevant than ever.

Modern technology, including satellite observations and advanced computational models, allow us to analyze solar activity with unprecedented precision.

However, historical data like Kepler’s sunspot sketches provides a critical context for understanding long-term solar cycles and their impact on Earth’s climate.

Kepler’s observations not only enrich our understanding of the sun’s past behavior but also illuminate pathways for future inquiry.

By honoring his legacy and applying modern techniques to historical data, we can unlock new insights into the intricate relationship between solar activity and life on Earth, ensuring that the mysteries of our star continue to inspire and inform generations to come.

Image Credit: NASA’s Solar Dynamic Observatory

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–