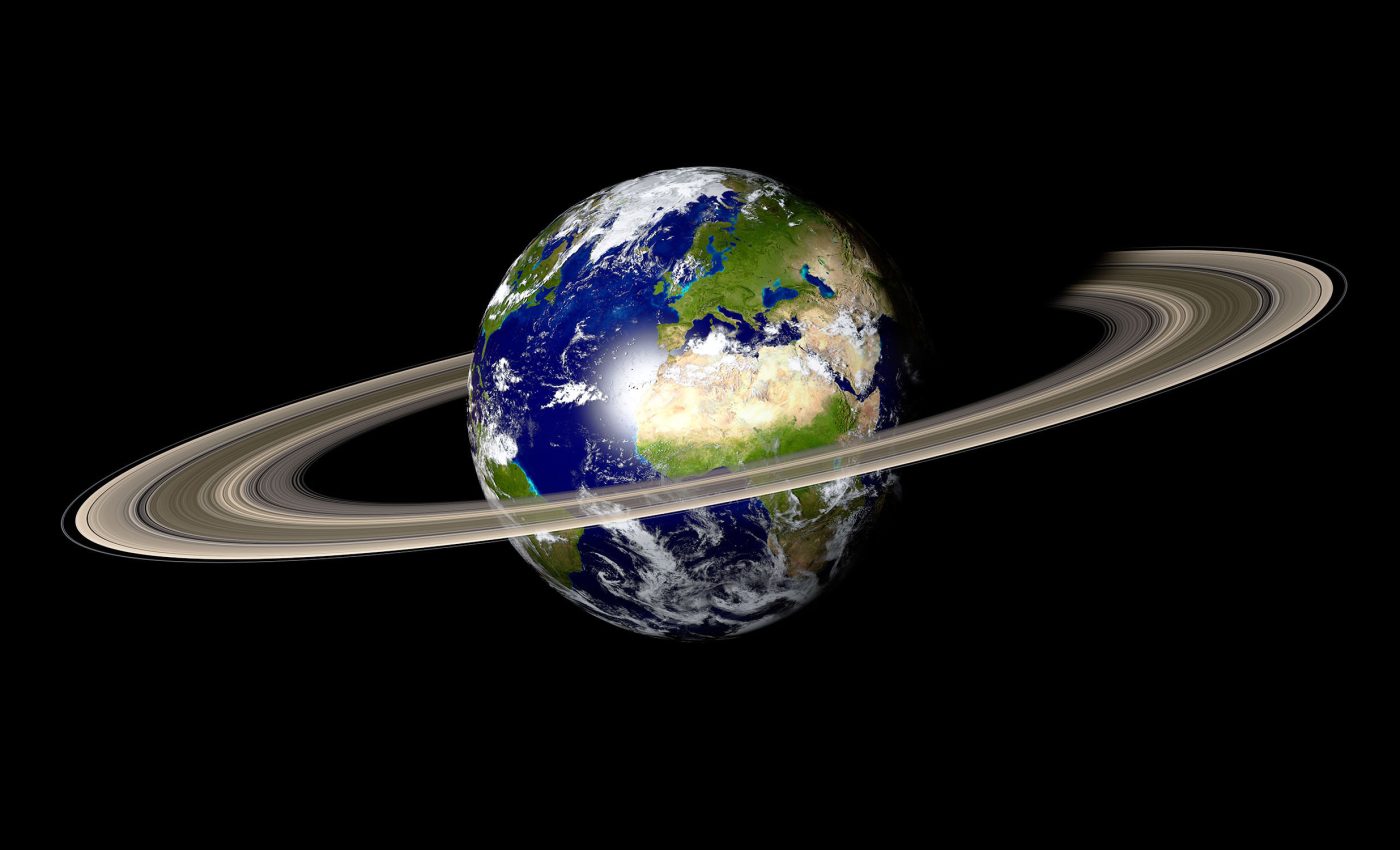

Earth had a ring system like Saturn roughly 466 million years ago

Earth may once have had a vast ring system circling the planet, very similar to Saturn’s rings, according to a recent study.

These rings seem to have formed around 466 million years ago, during a tumultuous era marked by intense meteorite bombardment known as the Ordovician impact spike.

This period was characterized by significant environmental changes, and the existence of rings may provide insight into our planet’s dynamics at that time and its interactions with cosmic forces.

This thought-provoking theory stems from a recent study led by Professor Andy Tomkins of Monash University, who has dedicated years to investigating geological evidence and astronomical data.

This revelation could transform our understanding of Earth’s geological evolution and its role within the solar system.

Earth rings could explain impact craters

The research team based their hypothesis on the intriguing positions of 21 asteroid impact craters, all located within 30 degrees of the equator. This is a peculiar finding because, typically, impact craters are randomly distributed across the globe.

However, in this case, more than 70% of Earth’s landmass was outside this equatorial region during the Ordovician period, making the clustered craters an anomaly that standard geological theories cannot easily explain.

The team’s idea is that this unusual pattern of impacts might be the result of a large asteroid having a close encounter with Earth.

As it neared the planet, the asteroid would have crossed Earth’s Roche limit — a point where tidal forces become so strong that they can tear a celestial body apart.

This would have led to the formation of a debris ring around Earth, similar to the rings that we see around gas giants like Saturn today.

“Over millions of years, material from this ring gradually fell to Earth, creating the spike in meteorite impacts observed in the geological record,” Tomkins explained.

“We also see that layers in sedimentary rocks from this period contain extraordinary amounts of meteorite debris.”

Understanding the Ordovician period

The Ordovician period happened about 485 to 444 million years ago. It was a time when a lot changed on Earth. Many new types of sea life evolved during this time, including the first fish.

There were also lots of animals without backbones, like trilobites and early shellfish.

Consequently, the oceans were teeming with life, and coral reefs started to form, creating homes for many different sea creatures.

The Earth itself changed a lot during the Ordovician period.

At first, it was warm, like the tropics, but by the end of this time, there was a big ice age, which made sea levels drop significantly, resulting in widespread extinctions.

Despite these challenges, the Ordovician period set the stage for future evolutionary developments, leaving a lasting impact on the history of life on Earth.

Connection to a global cooling event

But the implications of this discovery go beyond mere geology. The researchers speculate that this ring system might have had significant climate impacts, particularly contributing to a global cooling event known as the “Hirnantian Icehouse.”

This period, occurring near the end of the Ordovician, is recognized as one of the coldest times in the last 500 million years.

The idea is that the ring system could have cast a shadow over Earth, blocking sunlight and causing temperatures to drop.

“The idea that a ring system could have influenced global temperatures adds a new layer of complexity to our understanding of how extra-terrestrial events may have shaped Earth’s climate,” Professor Tomkins explained.

How the study was conducted

To reach these conclusions, the team employed a Geographic Information System (GIS) to analyze the distribution of the Ordovician impact craters.

They focused on stable, undisturbed cratons — ancient, stable parts of the continental crust — that were geologically capable of preserving craters from that era.

By excluding areas that were buried under sediment, ice, or affected by tectonic activity, the researchers identified regions like Western Australia, Africa, the North American Craton, and parts of Europe as the most likely places to find these ancient craters.

Despite only 30% of the suitable land area being close to the equator, all the identified craters from this period were found in this region.

The chances of this happening are like tossing a three-sided coin and getting the same side 21 times. This highly improbable distribution is what led the researchers to consider the possibility of an Earth ring system in the first place.

Earth rings: Why does it matter?

This discovery doesn’t just rewrite a chapter of Earth’s history — it opens an entirely new book.

The idea that Earth may have had a Saturn-like ring system raises fascinating questions about how such features might have influenced not just our planet’s climate but also the development of life itself.

Could other ancient ring systems have existed at different points in Earth’s history? How might they have shaped the environment in ways we are only beginning to understand?

While the notion of Earth with rings might sound like science fiction, it’s rooted in meticulous research and a willingness to question established theories.

This study, published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters, provides a fresh perspective on the dynamic interactions between our planet and the wider cosmos.

What happens next?

The implications of this study extend well beyond the Ordovician period, urging us to reevaluate the broader influence of celestial events on Earth’s evolutionary trajectory.

As scientists continue to explore this new theory, they may uncover a past that is far more intricate and intertwined with cosmic phenomena than we previously thought.

Could similar rings have emerged during other pivotal moments in Earth’s history, potentially influencing everything from climate patterns to the distribution of life? Only time, and science, will tell.

The full study was published in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–