Scorpion and spider ancestor located in 500-million-year-old fossil site

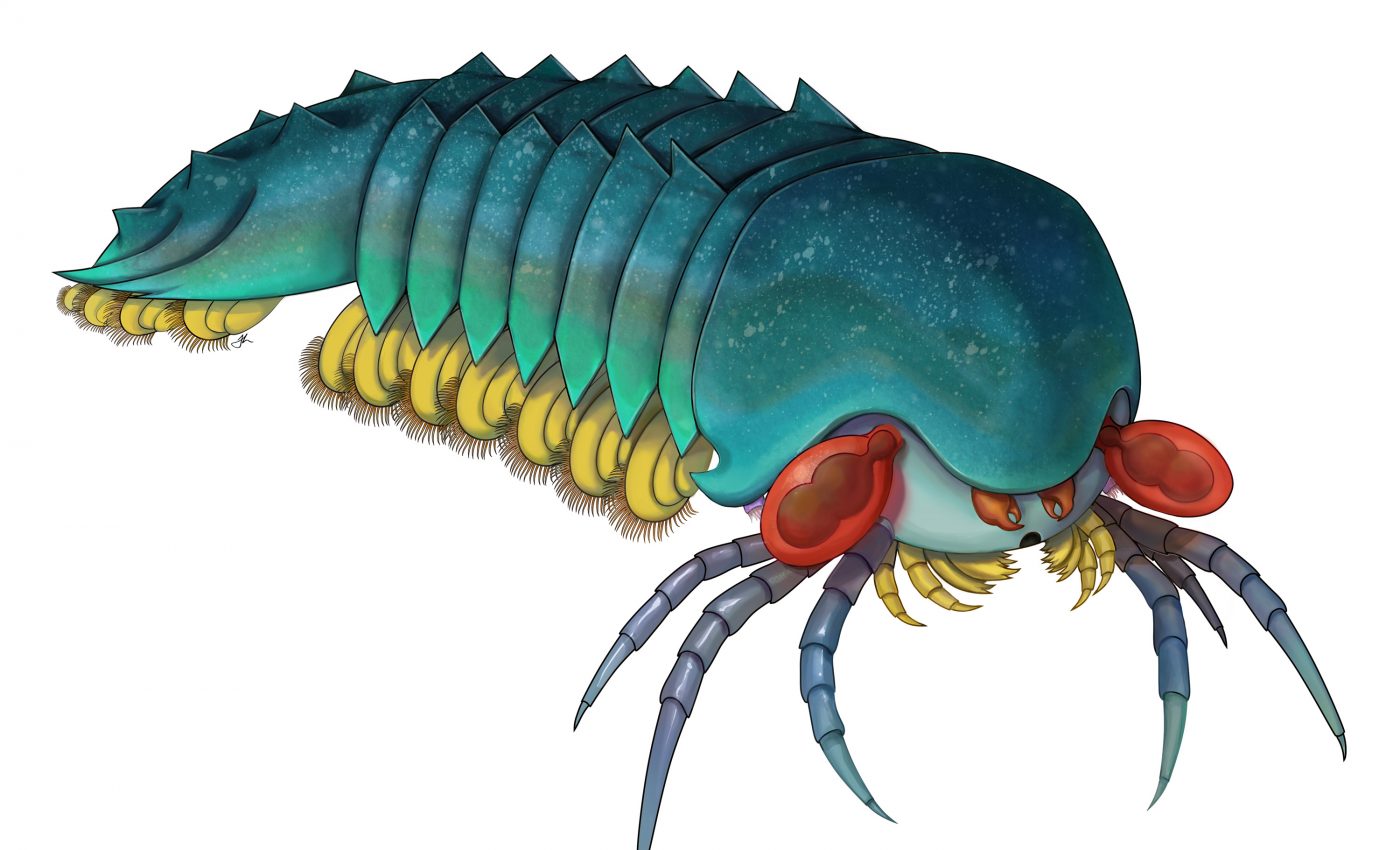

Scorpion and spider ancestor located in 500-million-year-old fossil site. The world’s oldest chelicerate, a group of predatory animals including horseshoe crabs, scorpions, and spiders, has been discovered in the Burgess Shale, located in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia. Dubbed Mollisonia plenovenatrix, paleontologists believe the fossil to be more than 500 million years old.

Despite its exoskeleton being discovered about a century ago, this new fossil exhibits more evidence of what the creature originally looked like. Scorpion and spider ancestor located in 500-million-year-old fossil site

“It is the first time that evidence of the limbs and other soft-tissues of this type of animal are described, which were key to revealing its affinity,” said co-author Jean-Bernard Caron, the Richard M. Ivey Curator of Invertebrate Palaeontology at the Royal Ontario Museum.

The fossil shows that M. plenovenatrix would have been about the size of one’s thumb with large, egg-shaped eyes, and a “multi-tool head.” It had long legs as well as several pairs of limbs that would help it sense, grasp, crush, and chew its prey. But the most important feature of the creature is that it had a pair of “pincers” at the front of its mouth, called chelicerae, which are seen in modern scorpions and spiders.

“Before this discovery, we couldn’t pinpoint the chelicerae in other Cambrian fossils, although some of them clearly have chelicerate-like characteristics,” said lead author Cédric Aria of the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology, and is a member of the Royal Ontario Museum’s Burgess Shale expeditions since 2012. “This key feature, this coat of arms of the chelicerates, was still missing.”

Other features of the fossil, such as the gill-like back limbs, point to the fact that it was already morphologically similar to modern spiders, rather than a primitive version.

“Chelicerates have what we call either book gills or book lungs,” Aria said. “They are respiratory organs are made of many collated thin sheets, like a book. This greatly increases surface area and therefore gas exchange efficiency. Mollisonia had appendages made up with the equivalent of only three of these sheets, which probably evolved from simpler limbs.”

It is believed that this creature hunted close to the sea floor, and because of its modern appearance, the research team thinks chelicerates prospered quickly and their origin potentially lies deeper within the Cambrian period.

“Evidence is converging towards picturing the Cambrian explosion as even swifter than what we thought,” said Aria. “Finding a fossil site like the Burgess Shale at the very beginning of the Cambrian would be like looking into the eye of the cyclone.”

This new discovery is published in Nature.

—

By Olivia Harvey, Earth.com Staff Writer

Main Image Illustration by Joanna Liang © Royal Ontario Museum