RNA recovered from an extinct species in a big boost for de-extinction efforts

In a momentous scientific leap, researchers have successfully sequenced RNA from an extinct Tasmanian tiger specimen that is over a century old. This achievement marks a significant milestone in the field of genetics and paleogenomics.

For the first time, transcriptomes — essentially the complete sets of RNA transcripts from an organism — have been reconstructed for an extinct species, providing unprecedented insights into the biology of the Tasmanian tiger.

Emilio Mármol, the study’s lead author and a dedicated researcher at SciLifeLab, underscores the importance of this venture.

“Resurrecting the Tasmanian tiger or the woolly mammoth is not a trivial task and will require a deep knowledge of both the genome and transcriptome regulation of such renowned species, something that only now is starting to be revealed,” he enthused.

This impressive scientific endeavor broadens our understanding of the genetic makeup of these fascinating creatures while bringing researchers ever closer to future efforts in de-extinction, highlighting the intricate connection between genetics, evolution, and the survival of species.

What is a Tasmanian Tiger?

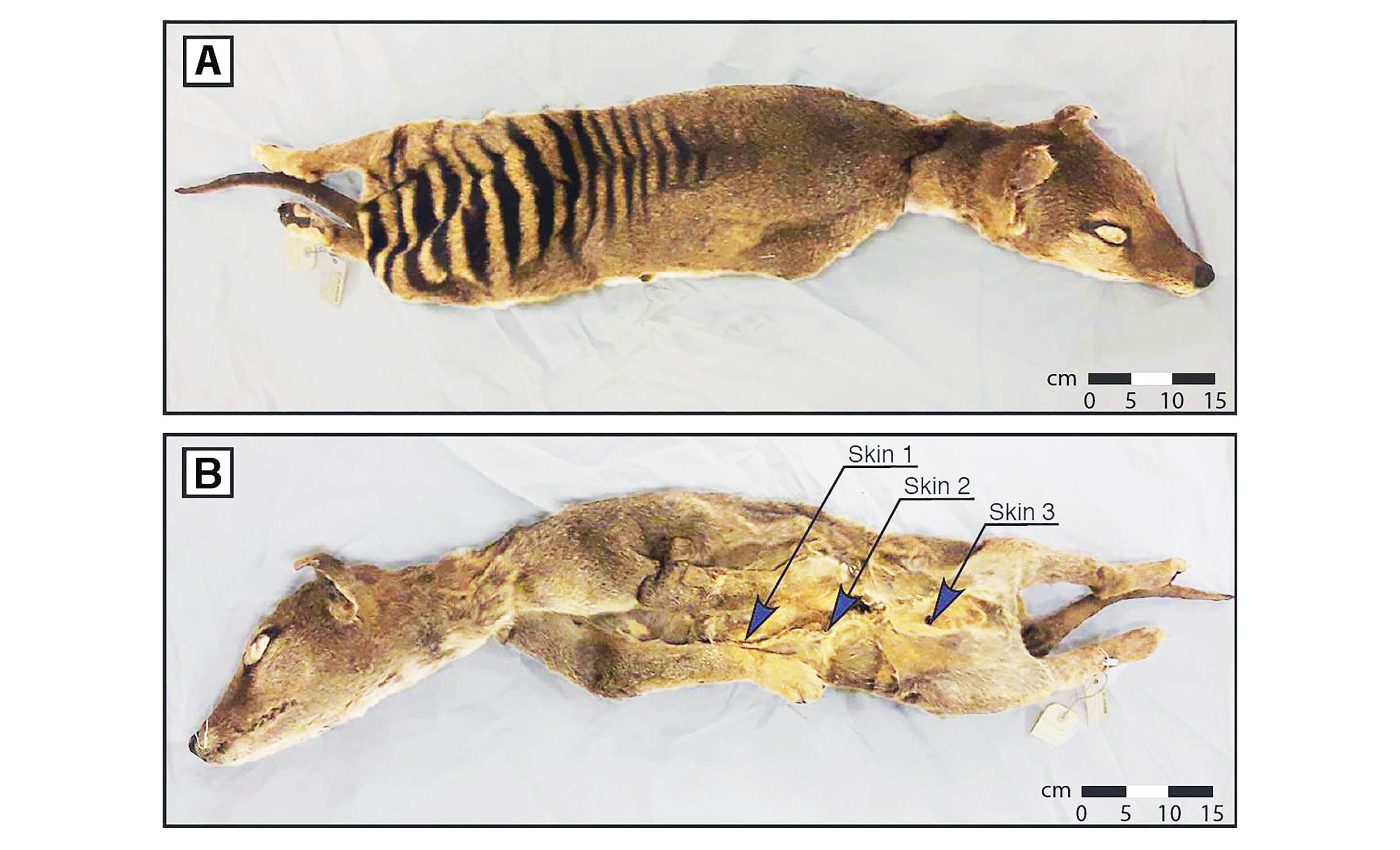

The Tasmanian Tiger, or thylacine, was a carnivorous marsupial that once roamed Australia, Tasmania, and New Guinea. It looked a bit like a dog but had tiger-like stripes on its lower back, along with a stiff tail, big jaws, and a pouch like a kangaroo.

Even though it gave off wild canine vibes, the thylacine was actually part of a totally different evolutionary group, which highlights the fascinating idea of convergent evolution.

Adult thylacines usually weighed around 30 kilograms (66 pounds), with males being a bit bigger than females. They were nocturnal hunters, going after small mammals and birds using their sharp eyesight and strong jaws.

Sadly, the thylacine was driven to extinction in the early 20th century, mainly because of human activities. European settlers hunted them down, mistakenly blaming them for taking out livestock. Habitat destruction and competition with introduced species also took a toll on their numbers.

The last known Tasmanian Tiger died in captivity in 1936 at the Hobart Zoo, marking a sad end for one of the most unique marsupials on Earth.

Pulling RNA from an extinct animal

The Tasmanian tiger’s extinction in the early 20th century was a significant loss for our planet, but this research breakthrough opens the door to understanding it and other extinct species more deeply than ever before.

The researchers’ work helps us understand how a species lived, functioned, and evolved.

This was achieved by constructing the skin and skeletal muscle transcriptomes — an invaluable step towards de-extinction and understanding RNA viruses’ evolution.

De-extinction requires more than just DNA

Now, most efforts in de-extinction concentrate on DNA. Though essential, DNA tells only part of the story.

To get a more comprehensive picture, researchers need to decode RNA, the molecules carrying genetic instructions for building proteins.

In this important study, researchers sequenced RNA gleaned from a Tasmanian tiger specimen that had been preserved at room temperature for over 130 years at the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm.

“This is the first time that we have had a glimpse into the existence of thylacine-specific regulatory genes, such as microRNAs, that got extinct more than one century ago,” noted Marc R. Friedländer, an Associate Professor at Stockholm University

While DNA is the life blueprint, RNA is the project manager, directing which genes are expressed when. With the Tasmanian tiger’s transcriptome in hand, scientists now possess a trove of data that could be pivotal for de-extinction efforts.

Mármol and his team used cutting-edge techniques to identify high-quality RNA molecules, filling gaps in our understanding of how genes were regulated in extinct species and providing a richer picture of the biological functions that characterized the Tasmanian tiger.

Next steps towards de-extinction

Imagine what we could learn from the vast collection of specimens and tissues stored in museums across the globe.

Who knew that these seemingly unassuming archives could be gold mines of genetic information waiting to be discovered?

But, as Love Dalén, a Professor of evolutionary genomics at Stockholm University, points out, the implications extend beyond extinct animals.

“In the future, we may be able to recover RNA not only from extinct animals but also RNA virus genomes such as SARS-CoV-2 and their evolutionary precursors from the skins of bats and other host organisms held in museum collections,” Dalén explained.

Bringing back extinct species with RNA

With the integration of genomics and transcriptomics, we’re moving closer to a holistic understanding of what it takes to bring a species back to life.

A giant leap has been taken, but the journey is long, and we still need to understand the environment, behavior, and role within the ecosystem before reintroducing a species.

So, what’s your take? Would you like to see a Tasmanian tiger roaming the earth again, or should we leave nature be? The conversation is just beginning.

The full study was published in the journal Genome Research.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–