Study suggests a new reason for the rapid global temperature surge

Heat records fell all around the world last year. Greenhouse gases were high, and El Niño was strong. Even so, the unexpected level of the temperature increase surprised researchers who watch Earth’s energy balance.

A detailed global study helped scientists find another key piece of the puzzle: Earth reflected less sunlight back to space than usual.

When reflectivity drops, more solar energy stays in the system. That extra energy helped push temperatures higher than expected from greenhouse gases and El Niño alone.

Understanding cloud albedo

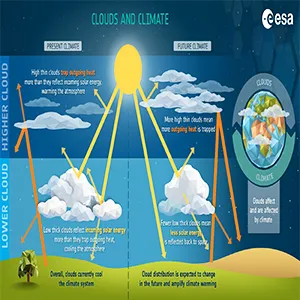

Albedo is the fraction of sunlight that the planet reflects. Bright surfaces reflect more. Dark surfaces reflect less. When global albedo falls, the system takes in more solar energy. Extra energy drives warming.

Low clouds usually matter most for albedo and sunlight reflection. They tend to bounce a lot of sunlight back to space and don’t trap much heat. High clouds behave differently because they can slow the escape of heat to space.

The researchers treated Earth like an energy budget. On one side is incoming sunlight. On the other side is heat leaving for space.

They compared measurements of reflected sunlight and emitted heat to see how the net balance shifted in 2023.

They also used atmospheric reconstructions that combine many data sources into an hour‑by‑hour picture of clouds and radiation. Both approaches showed the same thing: reflectivity dropped sharply in 2023.

Albedo cloud pattern that stood out

Low cloud cover declined in key regions. The signal showed up in parts of the northern mid‑latitudes and the tropics.

With fewer of these bright clouds, less sunlight was reflected. More sunlight reached the ocean and land, and surface temperatures climbed.

High clouds did not explain the recent change. The big swing came from the low clouds that normally provide strong reflection over large ocean areas.

The North Atlantic stood out. Sea surface temperatures there were already unusually warm. At the same time, low clouds thinned.

Warmer water can favor fewer bright low clouds. Fewer bright clouds then allow more sunlight in, which warms the surface even more. That feedback reinforced the heat.

What about the poles? Melting sea ice does lower surface reflectivity. But the observed sea‑ice changes could not explain the planet‑wide dip in 2023. The dominant driver was the change in cloud albedo.

How much warming it added

To estimate the temperature effect, the team used an “energy‑budget” model. It converts a change in reflectivity into an expected shift in temperature.

Their calculation suggests that, without the drop in albedo from late 2020 through 2023, global temperature in 2023 would have been cooler by a few‑tenths of a degree Celsius.

That estimate matches the unexplained gap scientists had noticed when they compared observations with the usual drivers.

Fewer low clouds means less albedo

Natural variability is one candidate. Internal climate swings can shift winds, humidity, and stability in the lower atmosphere. Those shifts can reduce low‑cloud formation in some regions for a year or two.

Cleaner air likely played a role as well. Tiny particles called aerosols, many from fuel combustion and shipping, help seed cloud droplets and also reflect sunlight.

As sulfur pollution has dropped along major shipping routes and on land, the air contains fewer of these particles. Fewer particles can mean fewer or less reflective low clouds over the oceans.

A third possibility is a feedback linked to warming: as oceans and air warm, some regions may favor fewer low clouds, which further lowers albedo and speeds up warming.

What this means for the next few years

If the change mainly reflects a temporary swing, reflectivity could bounce back and trim some of the recent extra warming. If cleaner air was a major cause, part of the albedo loss could persist unless other processes offset it.

If a warming‑low‑cloud feedback is strengthening, near‑term warming could run faster than many models expected.

That matters for widely watched thresholds. A lasting albedo drop would tighten the timeline for crossing 1.5°C above preindustrial levels and shrink the remaining carbon budget.

Clouds, albedo, and Earth’s future

The study points to clear priorities. Measure low‑cloud properties more precisely. Keep monitoring Earth’s energy flows from space so we can see shifts in near‑real time.

Watch how aerosol changes – especially from shipping – affect cloudiness and reflectivity over the oceans.

These steps will help sort the roles of natural variability, cleaner air, and warming‑driven feedbacks. They will also improve near‑term outlooks for regional heat and marine conditions.

In 2023, Earth reflected less sunlight than usual because low clouds pulled back in important regions, including the North Atlantic and parts of the tropics.

With lower albedo, more solar energy stayed in the system. That extra energy added to the heat from greenhouse gases and El Niño and helped set new temperature records.

Whether reflectivity rebounds, lingers at a lower level, or drops further will shape how quickly the climate warms over the next few years.

The full study was published in the journals Science and PNAS.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–