Psychedelic drugs secreted from toad skin greatly improve cognitive functioning

A combination of two psychedelic drugs demonstrated significant efficacy in treating a range of symptoms, including depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairments, in U.S. special operations forces veterans.

This novel approach might offer a beacon of hope for many veterans who do not find relief in traditional therapies.

Which psychedelic drugs were used?

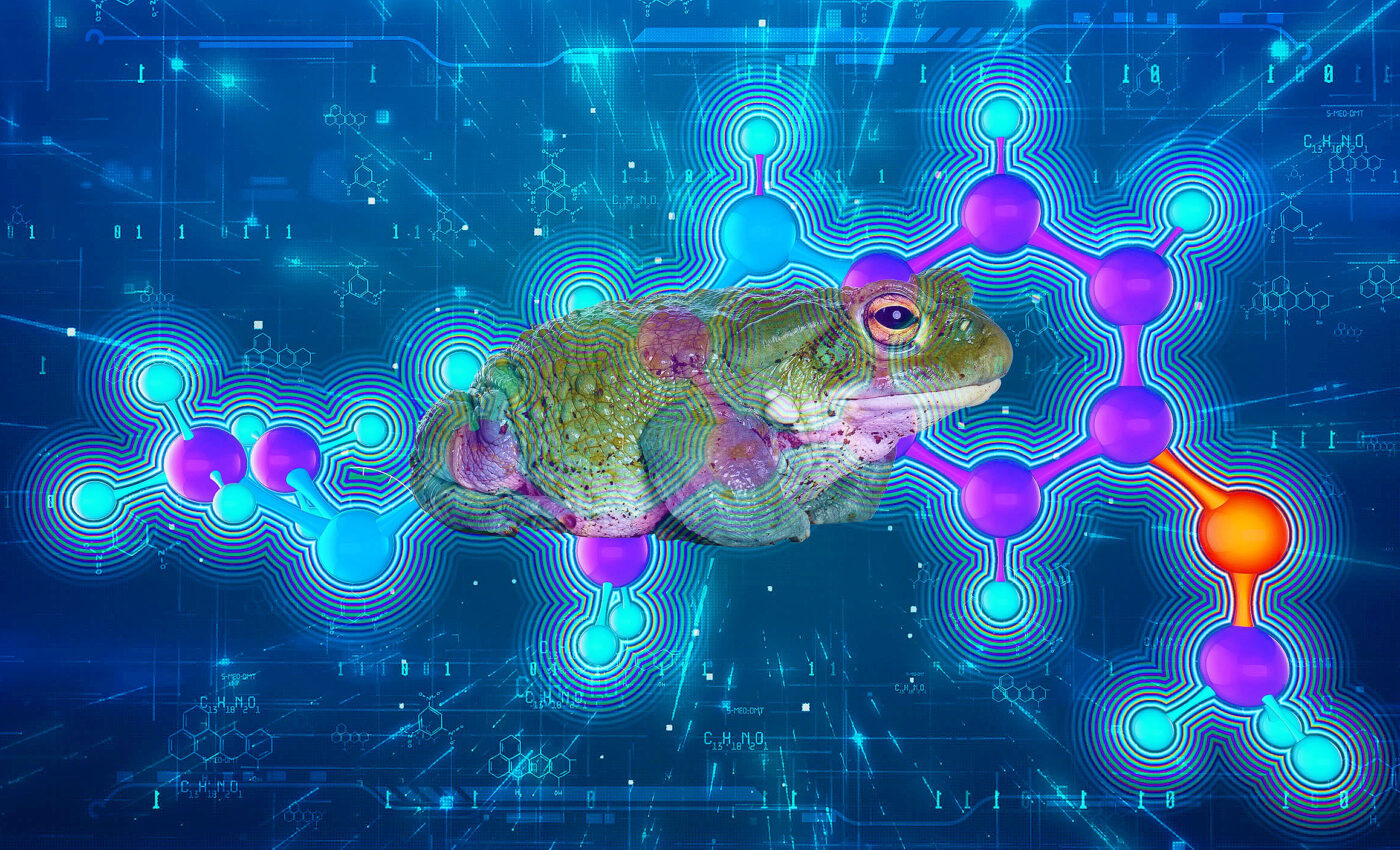

The treatment regimen combined two psychedelic drugs. The first, ibogaine hydrochloride, is sourced from the West African shrub called iboga. The second, 5-MeO-DMT, is a substance secreted from the Colorado River toad.

Both these substances are categorized as Schedule I drugs under the U.S. Controlled Substances Act, a classification reserved for drugs with no current accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.

This research, spearheaded by The Ohio State University, discovered not only alleviation in symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) but also a noteworthy improvement in cognitive functions related to traumatic brain injury. The latter finding was especially unexpected and sheds new light on the vast potential of psychedelic treatments.

Unique challenges in treating veterans

Alan Davis, the lead author and the director of the Center for Psychedelic Drug Research and Education (CPDRE) at Ohio State’s College of Social Work, emphasized the unique challenges faced by special operations forces veterans.

“Their routine exposure to traumatic events often results in a mix of problems including traumatic brain injury, which predisposes them to a plethora of mental health challenges,” said Davis. He noted the most “striking results” were the observed improvements in cognitive functioning linked to brain injuries.

How the study was conducted

Most of the veterans in this study involving psychedelic drugs had been on active duty post the 9/11 tragedy. They sought care for a gamut of issues ranging from memory problems, depression, PTSD to sleep disturbances, fatigue, and anger. An astounding 86% of these veterans had experienced head injuries, attributing many of their symptoms to these past traumas.

To measure the efficacy of the treatment, 86 veterans were asked to complete pre-treatment questionnaires that gauged various mental health symptoms. The treatment protocol involved administering a single oral dose of ibogaine hydrochloride and inhalation doses of 5-MeO-DMT on separate days. These drug administrations were flanked by preparation and reflection sessions.

Therapy results from the psychedelic drugs

The results were indeed promising. A month after the treatment, the veterans reported significant improvements in symptoms of PTSD, depression, anger, and insomnia. Moreover, there was a substantial uptick in their life satisfaction.

These benefits remained consistent even at the three- and six-month post-treatment check-ins. Furthermore, the veterans experienced improvements in disability, post-concussive symptoms, and showcased tremendous growth in psychological flexibility and cognitive function.

The latter, improved cognitive function, piqued Davis’s interest. He believes further investigation is needed to discern whether this improvement stems from a reduction in mental health symptoms, biological alterations in the brain’s signaling, or a combination of both.

Insightful and mystical experiences reported

Moreover, Davis highlighted the association of psychological flexibility with insightful and mystical experiences induced by psychedelics. “The higher one’s psychological flexibility, the more probable is the reduction or mitigation of one’s mental health symptoms,” he explained.

Post-treatment feedback also revealed intriguing insights into the veterans’ personal experiences. Almost half described their psychedelic experience as the most spiritually significant or psychologically insightful of their lives. However, a smaller fraction (17.1%) also found it to be the most challenging experience they ever encountered.

To ensure the integrity of their findings, Davis and his team adopted a conservative data analysis approach, accounting for the possibility that non-respondents might not have derived the desired benefits from the treatment.

The positive outcomes of this research emphasize the potential of psychedelic-assisted therapies, particularly for veterans with intricate trauma histories. This underscores the need to further explore psychedelic therapies in U.S. clinical trials. Notably, Ohio State is already diving deeper into the realm by studying psilocybin-assisted therapy for PTSD treatment among military veterans.

For those keen on delving into the intricate details of this study, it’s published in the esteemed American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse.

—

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

—

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.