Planet Mercury is still shrinking and now has more wrinkles

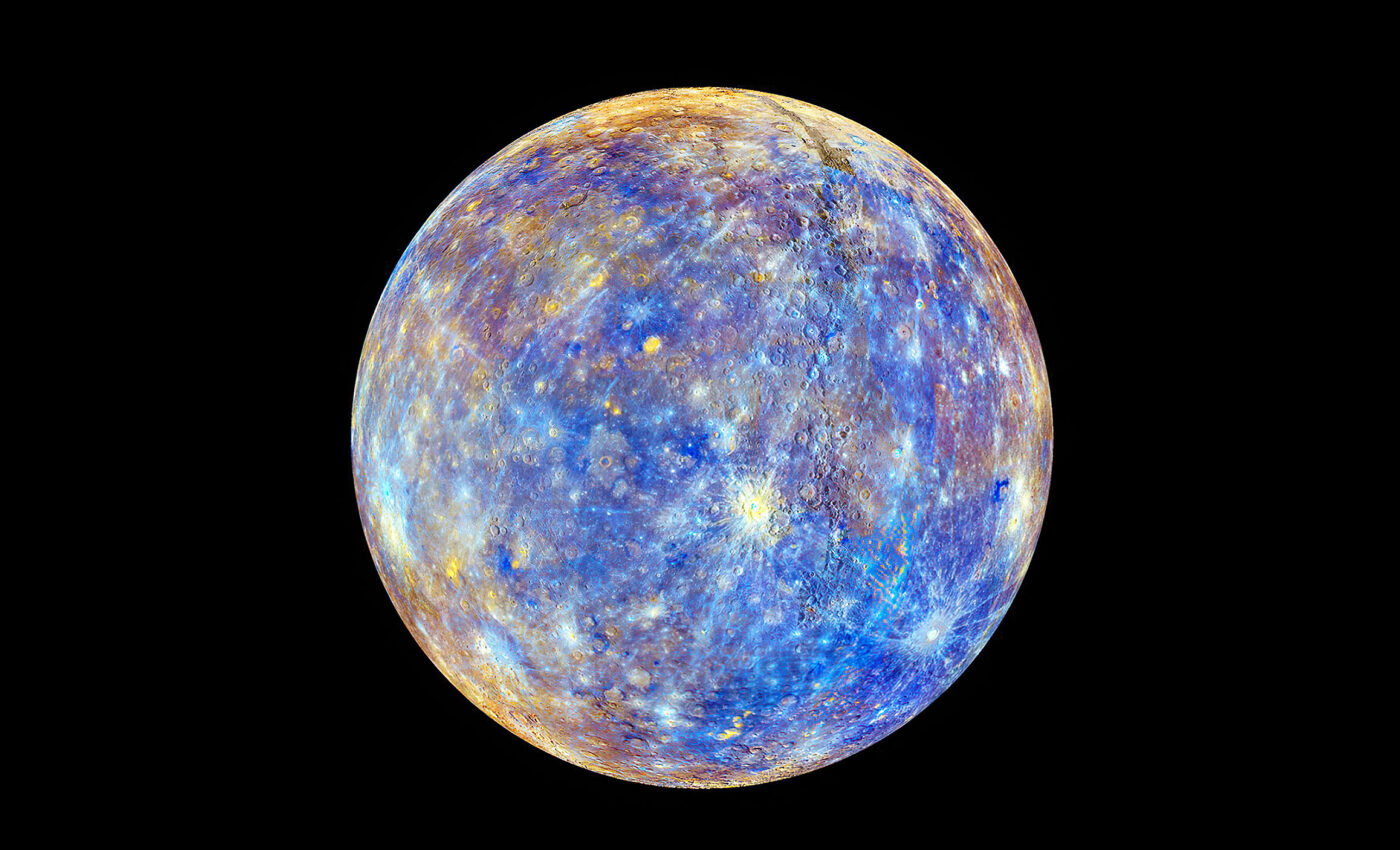

Despite shrinking for the last three billion years, there are strong reasons to suggest that Mercury, the smallest planet in the solar system, is still shrinking. In addition, the reduction in Mercury’s radius now comes with more wrinkles.

What we know about Mercury’s shrinking

We know all planets lose heat over time, and Mercury is no exception. The planet’s closeness to the Sun could not stop internal heat from leaking away over the years. Heat loss also means the volume of the rock and metal making up its internal composition has reduced considerably.

Scientists have estimated Mercury’s radius to have reduced by 7 km since the first evidence of its shrinkage in 1974. Over the years, the reduction has led to the appearance of wrinkles, also known as “scarps,” on the planet’s surface.

But what we do not know is the current rate of reduction in Mercury’s radius, and for how long the process will continue.

Shrinking of Mercury becoming more significant

According to new research published in Nature Geoscience, Mercury may be recording its most significant shrinkage in recent times. The study, conducted by scientists from The Open University in the United Kingdom, reported the widespread occurrence of a unique geological structure. Called grabens, they were discovered from global mapping of tectonic features using imagery from the MESSENGER mission.

Before now, scientists have relied on the appearance of wrinkles, or scarps, to prove that Mercury is indeed shrinking. But these geological structures are too old, dating back to about three billion years ago.

Rather than using scarps, this current study focused on grabens, which the scientists described as “some scarps with small fractures piggy-backing on their stretched upper surfaces.”

Implications of grabens

Although grabens are also geological structures, they offer an advantage over scarps with their slightness. These structures are small, with 0.6 miles of length with about 300 feet of depth.

Grabens are formed due to the stretching of the planet’s crust. While it is not unusual for the crust of a planet like Mercury to stretch, scientists observed that the formation of grabens, in this case, is due to the bending of the crust.

As noted by the authors in their paper, the identified grabens are about 10 to 150 m deep, tens of kilometers in length, and generally less than 1 km wide. In addition, the occurrence of the grabens as secondary tectonic features on larger compressional tectonic structures indicates “continued activity of parent structure.”

With 48 definite grabens and 244 likely grabens identified from the pictures obtained from NASA’s MESSENGER 2015 probe, the scientists concluded that these geological structures are about 300 million years old or younger.

“We estimate that they must be ~300 million years old or younger; otherwise, impact gardening would have masked their signature by burial and infilling.” Based on the spread and young age of the grabens, the study also established “continued activity of Mercury’s shortening structures into geologically recent times.”

What next for Mercury?

David Rothery, professor of planetary geosciences at UK’s Open University and an author on the study, believes the next step will be to wait for the BepiColombo.

The BepiColumbo was launched in 2018 to explore the planet’s surface from various angles. It is expected to take higher-resolution pictures of Mercury in late 2025 or early 2026, in addition to the one it took in 2021 while flying by the planet.

Perhaps BepiColombo’s new data can help unravel the mysteries of Mercury’s ongoing transformation and tell us more than we currently know.

—

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

—

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.