Mummified baby saber-toothed tiger found with fur and toes intact

The saber-toothed tiger, an iconic predator from the Ice Age, continues to captivate scientists and enthusiasts alike with its mysterious legacy. Now, scientists have discovered a mummified baby saber-toothed tiger in Siberia.

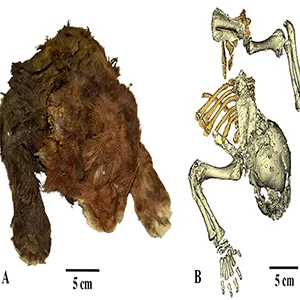

Radiocarbon tests on the preserved wool place the animal between 35,000 and 37,000 years old, a span that sits squarely in the age of mammoths, steppe bison, and cold, windswept steppes.

A team led by Alexey V. Lopatin from the Borissiak Paleontological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences has identified the frozen saber-toothed cat as belonging to Homotherium latidens.

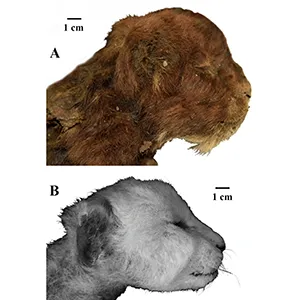

Whisker pads outline a face. Paws retain their pads. Enough exterior detail remains to compare soft‑tissue form with bone structure.

The discovery offers a rare and intimate glimpse into the anatomy and lifestyle of this long-extinct predator.

What are saber-toothed tigers?

Saber-toothed tigers, also called saber-toothed cats, were some of the most impressive predators to roam the Earth during the last Ice Age, even though they are not related to today’s tigers.

They sported incredibly long, curved canine teeth that could reach up to seven inches, perfect for delivering powerful, precise bites to their prey.

These big cats had strong, muscular bodies and relatively short legs, making them agile hunters capable of taking down large animals like mammoths and bison.

Their unique features and hunting strategies made them top predators in their ecosystems. Despite their fearsome reputation, saber-toothed tigers went extinct around 10,000 years ago.

Researchers believe a combination of climate change, habitat loss, and the decline of their primary prey contributed to their disappearance.

Mummified saber-toothed tiger cub

Permafrost locks biological material in ice and keeps microbes and oxygen from tearing tissues apart. In this case, the front portion of the saber-toothed tiger cub retained coat texture, skin outlines, and paw structure.

The face doesn’t match that of a lion cub. The muzzle shows a different shape, with a shorter, deeper front. The ears are small and sit low against the head, a layout that minimizes exposure.

The neck region looks thick for such a young animal, signaling early investment in the muscles that stabilize the head.

Proportions tell more of the story. The forelimbs appear relatively long, and the coat that remains looks dark, short, and dense. These traits match a life that demanded control of heat loss and traction day after day.

Skull clues under skin

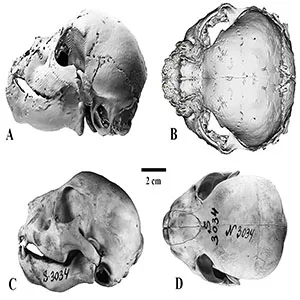

To study the interior without cutting, the team used a clinical CT scanner and built detailed three‑dimensional models.

They compared measurements with those of a modern lion cub at the same developmental stage. Based on tooth eruption, both individuals were about three weeks old. That age match kept the comparisons fair.

The mummy offers precious insights into the cat’s muscle structure and how it might have impacted its hunting methods.

The mummy’s face, forelimbs, torso, and part of its body were remarkably intact and generously covered with thick, soft fur that was between 0.8 and 1.2 inches (20 to 30 millimeters) in length.

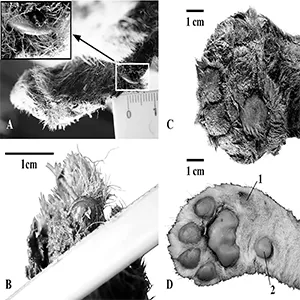

Feet and ears built for cold

The front paw has a broad, rounded pad – nearly as wide as it is long – unlike the more oval pads of a lion cub. Some of the small pads near the wrist are reduced or missing.

Squared, spread pads distribute body weight, which helps avoid punching through crusted snow and improves purchase on slick surfaces.

Small, low‑set ears reduce heat loss in subfreezing wind. Paired with dense fur and robust neck musculature, the ear layout supports steady movement and hunting in open, cold country.

Why this saber-toothed cub matters

The mummy is the first Asian record of the saber-toothed tiger species Homotherium latidens. Homotherium and Smilodon are both saber-toothed, yet they weren’t the same kind of hunter.

Homotherium carried somewhat shorter, scimitar‑like canines and a body built for longer runs across open ground.

Smilodon bore longer, more blade‑like canines and heavier forequarters suited to ambush. The cub’s jaw flange, wide gape, and early neck strength match the Homotherium toolkit.

Developmental timing carries information that adult skeletons can’t supply. Seeing these features in a three‑week‑old shows they were present from the start, not late add‑ons.

The mummy indicates later survival and wider spread across Eurasia than some expected from scattered bones alone, a reminder that permafrost sites can recalibrate range maps.

Other Ice Age mummies, like woolly rhinos and mammoths, have been found fairly commonly in the Siberian region. However, mummified cats are an extraordinary rarity.

Saber-toothed tiger fascination

This amazing discovery offers a unique insight into the entire evolutionary history of the feline group.

It expands what scattered bones alone could tell us and ties form to function with direct measurements from preserved soft tissue.

The result sharpens how we picture this cat: a runner of open ground, tuned to cold, carrying scimitar-like canines and the musculature to use them.

In short, a frozen half-pint turns guesswork into evidence and shows how careful imaging and context can rewrite a chapter of Ice Age life.

The research paper is published in the journal Scientific Reports.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–