Tiny plastic bits are now found hiding deep inside the human body

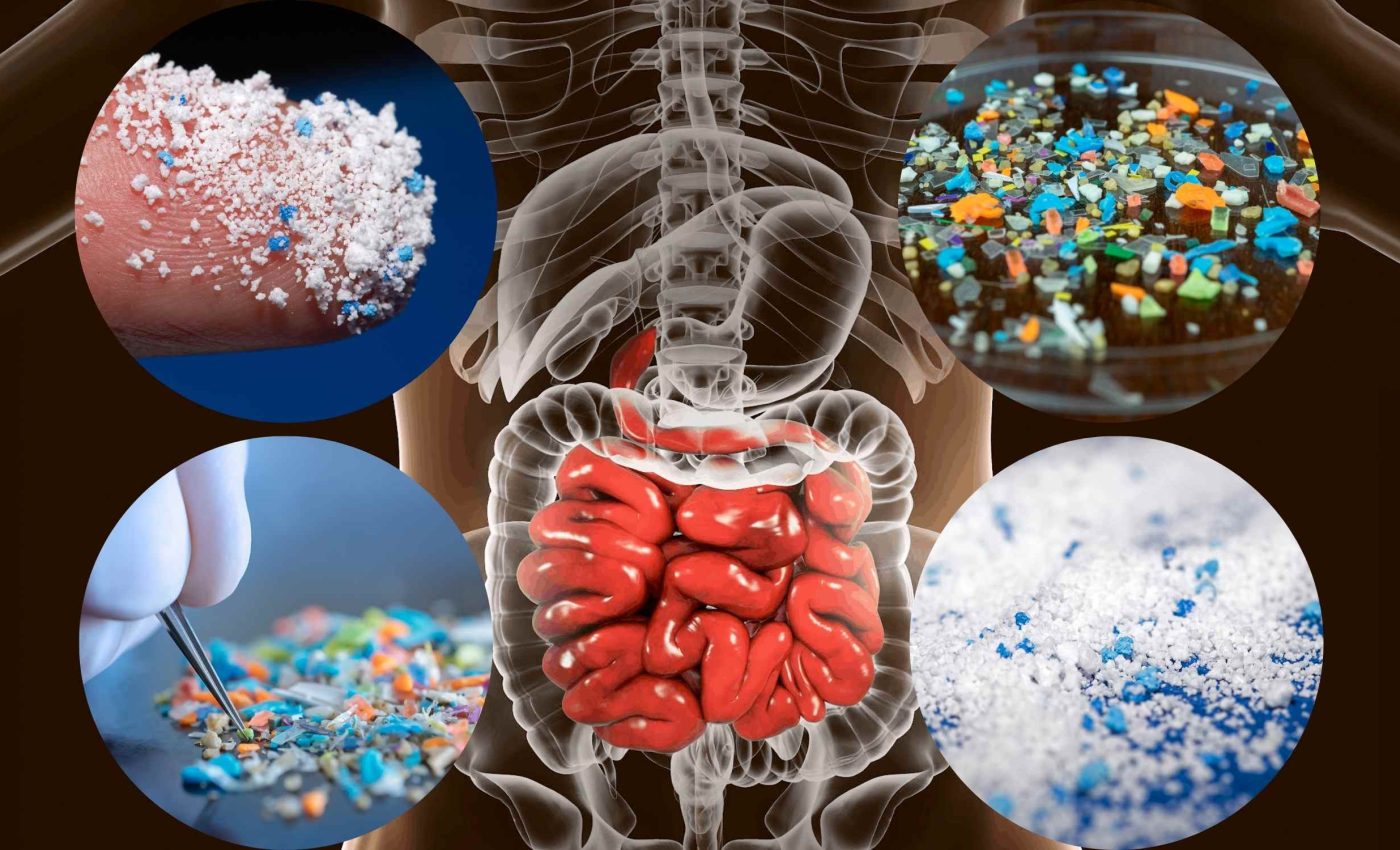

Tiny plastic fragments have turned up inside human beings, and it has rattled more than a few nerves. Nobody expects to find plastic in their blood or buried in important tissues, but recent research has done exactly that.

These miniscule particles, often smaller than a grain of sand, have appeared in places once thought safe from contamination.

This poses some uncomfortable questions about the implications for long-term health and whether anyone has been paying attention to this hidden hazard that has been present in the environment for decades.

The infiltration of plastic into human tissues

Scientists have identified micro- and nanoplastics (MNPs) in human lungs, gut, reproductive organs, and skin, where they can stick around for far longer than most people would imagine.

Their presence has now been detected in blood, too, making it clear that these tiny, synthetic particles move through our bodies in surprising ways. They do not simply pass through and exit without causing harm, as was once thought.

Instead, they take up residence. They linger, and they may be associated with some serious health issues.

This research, led by Dr. Yating Luo at the School of Ecological and Environmental Sciences, East China Normal University, and a team of specialists, has revealed an unsettling new source of environmental exposure.

Potential links to diseases

Other researchers have begun piecing together how MNPs might be involved in a range of health problems.

Studies have linked them to heart and blood vessel conditions, like atherosclerosis and thrombosis, as well as to intestinal diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease.

Some work even connects them to changes in reproductive systems and the risk of conditions like cervical cancer. Nobody wants to consider plastic dust as a potential player in such serious illnesses, but the evidence is mounting.

Dr. Luo, lead author of the study, which was published in Environment International, highlighted that the research strongly indicates MNPs are more than environmental contaminants – they are entering human tissues and may pose significant health risks.

How these particles break through barriers

Laboratory tests have shown that these particles can cross protective hurdles, including the body’s natural filters. For example, the blood-brain barrier has long been thought of as a sturdy shield, but these tiny plastic pieces may pass through it.

This could set the stage for neurological issues. Researchers suspect that if these minute fragments of plastic move along the gut-brain axis, they may influence how nerve cells work. Early evidence suggests they might play a role in some degenerative conditions that affect the brain.

Wider implications for public health

Plastic pollution is not something that stays outside in the ocean or piled up at landfills. Studies show that even remote corners of the planet have tiny plastic fragments floating in the air. People breathe them in, ingest them through food and water, and may even absorb them through the skin.

Dr. Tamara Galloway, a leading expert on microplastics from the University of Exeter, emphasized that this study further supports the increasing evidence of microplastics being widespread in human tissues.

It is not just a problem for one region or for certain groups. It is a global phenomenon that affects everyone, everywhere.

Why people should pay attention

Plastics have found their way into everyday life in a multitude of forms – containers, packaging, clothing, personal care products. As these items break down, tiny plastic fibers and fragments spread through land, water, and air. They turn up in fish and shellfish, which then end up on dinner plates.

Waste management practices in some places, such as open burning, add more plastic particles to the environment and harm people who live nearby.

Rethinking plastic use and environmental regulations

There is growing pressure on governments to enforce stricter rules around plastic manufacturing, recycling, and disposal. A shift to responsible materials and less reliance on single-use plastics could help slow the spread of these particles in future.

Public health agencies may need to update guidelines to consider tiny plastic fragments as contaminants. If MNPs are linked to certain diseases, official policies may need to reflect that. Health professionals might soon discuss plastic exposure as they do other known factors like poor air quality.

What comes next in the search for answers

Scientists need to measure the full extent of the problem. More long-term studies could show exactly how much plastic accumulates in human tissues and pinpoint how these particles alter cells and organs at a microscopic level.

Researchers are developing new technology to track these fragments and understand how they behave inside the body. Improved tools might help uncover the chemical reactions triggered by plastic fragments. With that information, they could figure out why certain tissues are more at risk than others.

Finding ways to reduce the danger

None of this is a reason to give up the fight against plastic pollution. People can reduce their own exposure by avoiding products that shed plastic fibers, pushing for cleaner water sources, and supporting brands that move away from plastic use.

Communities that suffer from poor waste management can advocate for better facilities, cleaner streets, and safer disposal methods.

Officials can encourage companies to design products with health and the environment in mind. Better filters and barriers could help keep these particles out of water supplies and the foods people rely on every day.

A reason to stay informed

Nobody likes to think about foreign particles building up in their body. For many, this may spark frustration or fear. The good news is that awareness can help drive action. If people know that these small bits of plastic may affect their health, they might push for meaningful changes.

More funding, better research, and stricter oversight may keep these hidden threats in check. As scientists learn more, the public can stay informed and join conversations that shape future policies.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–