Lucy spacecraft discovers asteroid Dinkinesh's complex geology

In November last year, the Lucy spacecraft, managed by the Southwest Research Institute, made a close encounter with the small main belt asteroid Dinkinesh during its mission.

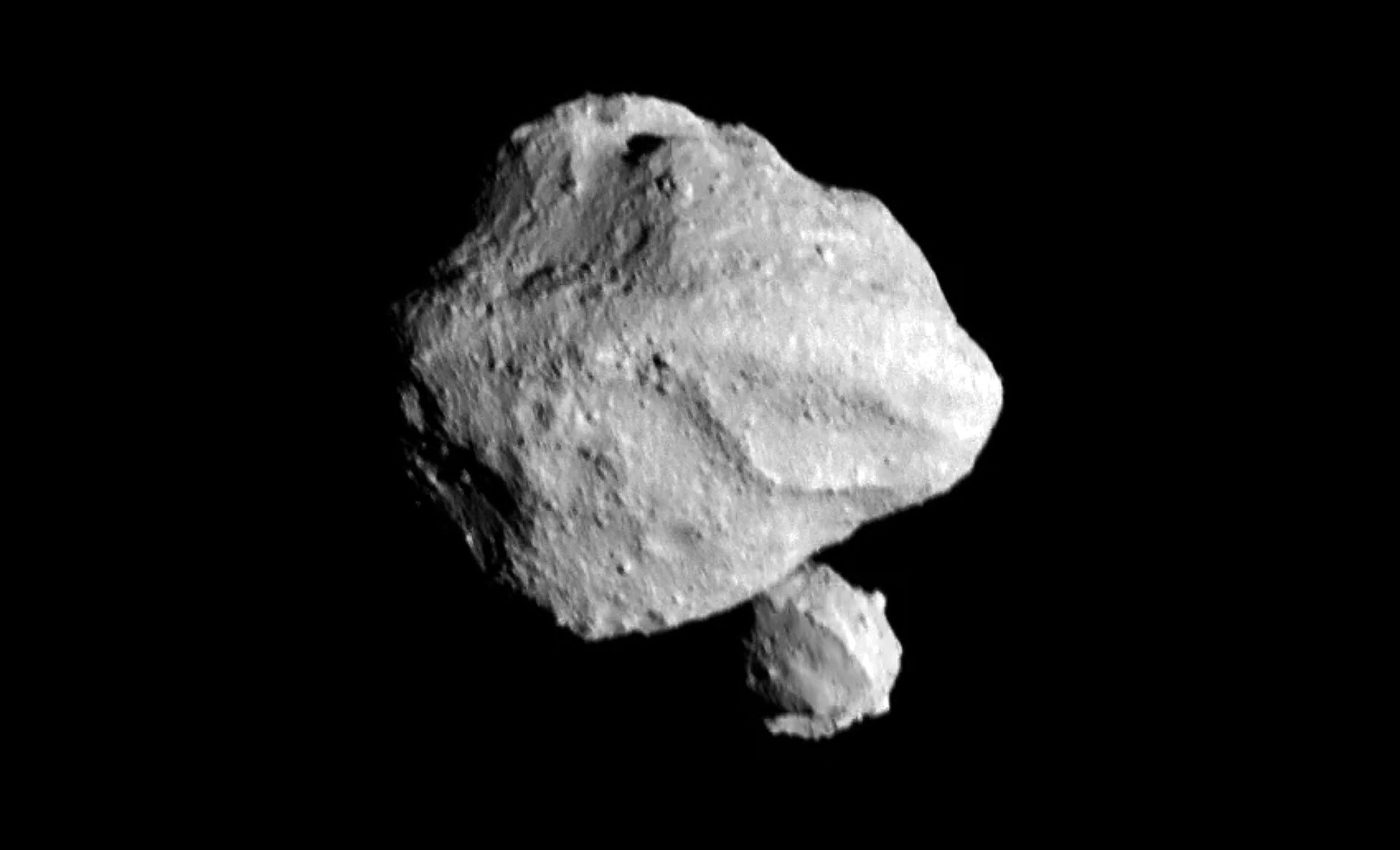

This half-mile-wide celestial body presented an unexpected and dramatic geological history, marked by sudden transformations and structural complexities.

The spacecraft’s flyby unveiled a distinctive trough and ridge configuration on asteroid Dinkinesh, along with a contact binary satellite — the first of its kind encountered in space.

Dynamic past of asteroid Dinkinesh

Researchers suggest that a significant shift of a large fragment on Dinkinesh led to the creation of the trough. This event scattered debris around the asteroid.

Some of this debris returned to the asteroid, contributing to the formation of the ridge, while other fragments amalgamated to form Selam, the contact binary satellite.

These formations indicate that both Dinkinesh and Selam possess remarkable internal strength and a vibrant, dynamic history.

Foundations of planetary formation

Hal Levison, the principal investigator for the Lucy mission, emphasized the importance of understanding collisions in space to grasp the history of planetary formation.

“To understand the history of planets like Earth, we need to understand how objects behave when they hit each other, which is affected by the strength of the planetary materials,” said SwRI’s Hal Levison, principal investigator for the Lucy mission and lead author.

“We think the planets formed as zillions of objects orbiting the Sun, like asteroids, ran into each other. Whether objects break apart when they hit or stick together has a lot to do with their strength and internal structure.”

Internal makeup of asteroid Dinkinesh

Over millennia, the surface of Dinkinesh was unevenly heated by the Sun, causing the asteroid to gradually spin faster.

This process built up stress that was eventually released, reshaping a large segment of the asteroid into an elongated form.

Simone Marchi, the Lucy mission‘s deputy principal investigator, shared insights from their preliminary observations.

“Thanks to the telescopic data, we thought we had quite a good picture of what Dinkinesh would look like, and we were thrilled to make so many unexpected discoveries,” said Marchi.

Archaeological insights

The strength and cohesive nature of Dinkinesh are more pronounced than those of other known asteroids, like Bennu, which resembles a rubble pile.

While Bennu’s fragmented materials might drift towards the equator and escape into space as it spins, Dinkinesh’s composition allowed it to maintain its integrity longer under stress, behaving more like a rock that suddenly fractures into large pieces.

“This flyby showed us Dinkinesh has some strength and allowed us to do a little ‘archeology’ to see how this tiny asteroid evolved,” Levison commented.

After it fractured, a disc of material formed around Dinkinesh, with some debris falling back to form the ridge, while the rest likely contributed to the formation of the unusual double-lobed moon, Selam.

Future explorations

Dinkinesh and its satellite Selam are just the beginning of Lucy’s extensive journey through space.

After skimming the inner edge of the main asteroid belt, Lucy is set to return to Earth for a gravity assist in December 2024.

This maneuver will catapult the spacecraft back into the main asteroid belt for further explorations, including a close approach to asteroid Donaldjohanson in 2025, followed by a tour of the Trojan asteroids starting in 2027.

As Lucy continues to traverse the cosmos, the insights gathered from Dinkinesh provide a glimpse into the intricate processes that shape our solar system, offering a deeper understanding of the dynamic interactions that may have led to the formation of planets and other celestial bodies.

More about asteroid Dinkinesh

Asteroid Dinkinesh, officially designated as 1996 HW1, resides in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Its name, “Dinkinesh,” means “you are marvelous” in Amharic, the official language of Ethiopia. The asteroid’s unusual geological features make it a fascinating subject for study.

Dinkinesh’s surface is a mosaic of craters, ridges, and troughs, indicating a tumultuous history of impacts and stress.

Spectroscopic analysis shows its composition includes silicate minerals, suggesting it is a stony asteroid. This composition provides clues about the conditions in the early solar system.

Dinkinesh rotates relatively slowly, taking about 20 hours to complete one spin. This slow rotation is unusual for an asteroid of its size, as most similar-sized asteroids spin faster.

Additionally, Dinkinesh’s contact binary satellite, Selam, is a rare find, offering a unique opportunity to study binary asteroid systems. The study of Dinkinesh can enhance our understanding of asteroid formation and evolution.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–