Lucy could barely run - what does that say about our ancestors?

Humans have a knack for getting around on two legs. Many of us take a long run for granted, trotting along city streets or forest trails without giving it much thought.

Unlike ancient human ancestors like Lucy, modern bodies power us forward at impressive speeds, with our muscles and tendons playing a crucial role.

But there was a time in our deep past when the earliest members of our family tree were nowhere near as quick.

A new study published in the journal Current Biology takes a careful look at the locomotive ability of one particular human ancestor, and the results are eye-opening.

The research was led by a team of natural scientists, musculoskeletal specialists, and evolutionary biologists affiliated with several institutions in the UK, in collaboration with a colleague from the Netherlands.

Lucy’s bones reveal her running skills

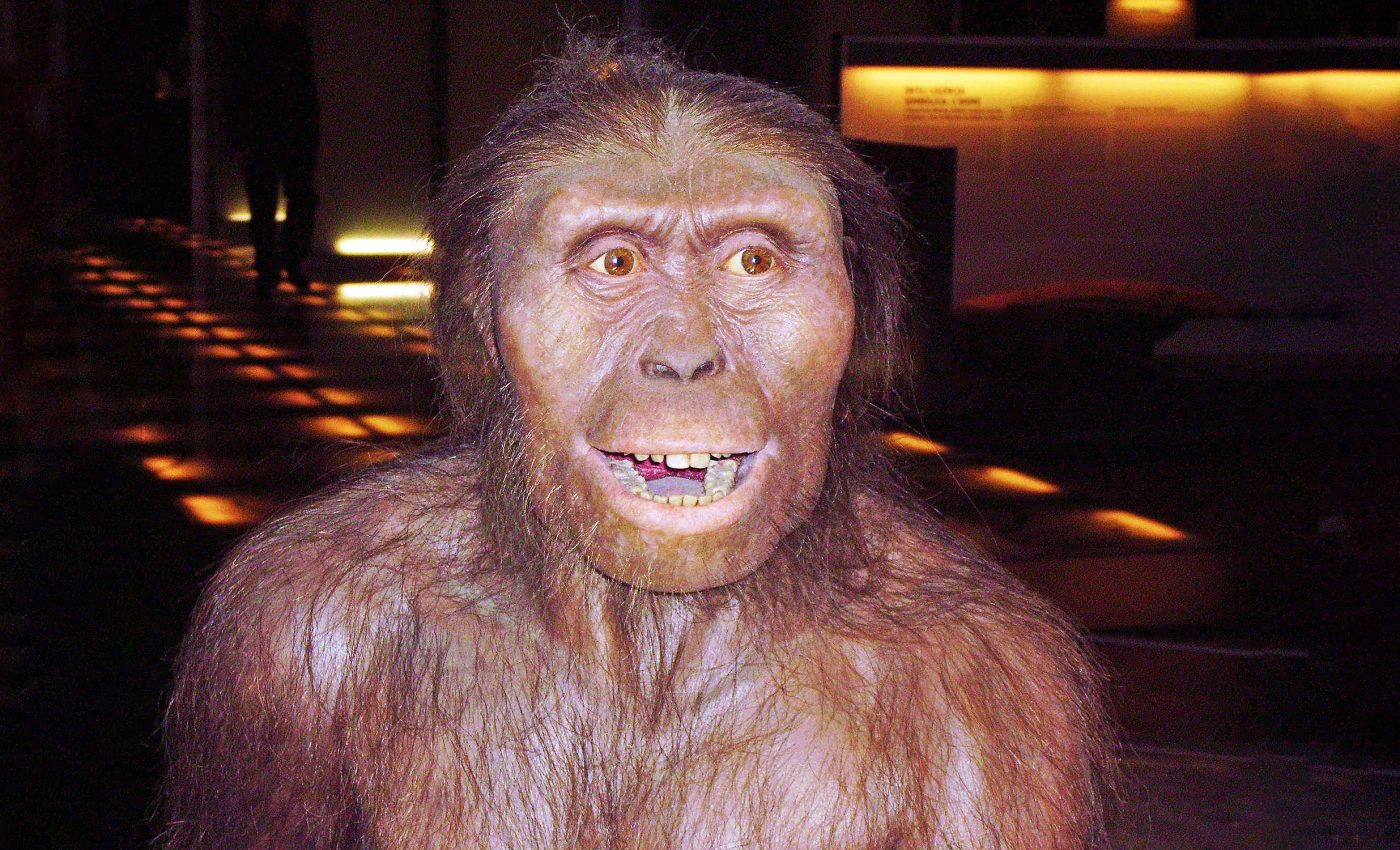

Roughly 3.2 million years ago, a hominin known as Australopithecus afarensis lived in East Africa. Fossils of one of its most famous members, Lucy, were found in 1974 in Ethiopia, shedding light on how early human relatives stood and moved.

Lucy’s skeleton showed that her species could walk upright on two legs, but her proportions and muscular arrangement were very different from what we see in humans today.

After studying her frame using 3D computer simulations, the researchers concluded that Lucy could run on two legs, yet she never matched the speeds that come so naturally to modern humans.

Putting Lucy’s running speed to the test

A digital model, shaped from Lucy’s fossil bones and data from modern apes, allowed the experts to study how her leg muscles might have worked.

The team plugged these details into a computer program that tried countless ways of activating muscles, then picked the best way to run as fast and efficiently as possible.

The results showed that even under ideal conditions, Lucy’s top speed was around 16 feet per second, much slower than a typical modern human who can easily push beyond 26 feet per second.

“It’s a very thorough approach,” explained Herman Pontzer, an evolutionary anthropologist at Duke University.

Searching for the hidden secret in muscles

Modern humans have a special setup in the lower leg. Compared to an ancient hominin, we carry a more elastic Achilles tendon linked to shorter muscle fibers.

This arrangement helps store and release energy during running, reducing the effort it takes to move forward. In Lucy’s time, these spring-like running features had not yet evolved.

Without them, even adding human-like muscles to her frame could not bring her speed up to modern standards.

“This tells us that the body shape of A. afarensis is significantly limiting its running speed compared to that of modern humans,” said Karl Bates, an evolutionary biomechanics researcher at the University of Liverpool.

What speed can say about survival

Running isn’t just about setting personal records. It plays a crucial role in how a species competes for food and escapes predators.

Modern humans, for example, can run long distances at a steady pace. By covering more ground, we found better opportunities to gather resources and cooperate.

Lucy’s species – with smaller frames and without the muscular tricks of modern legs – might not have covered long distances very well.

How body shape changed over time

Long legs, a defined Achilles tendon, and specific muscle structures did not just appear overnight. Early hominins began with a body design that was good for standing and walking upright.

Over generations, certain features shaped up, allowing humans to pick up the pace. As the genus Homo emerged, new body proportions offered better running ability, along with improved endurance.

This shift provided real-world advantages to our ancestors. By moving faster and more efficiently, they could reach distant places, follow game animals, and expand into new environments.

Features that help humans run

Walking upright and running well are not automatically the same thing. Lucy’s skeleton shows that even though her species walked on two legs, they did not run like we do. The skills and features that help humans run came along later.

Instead of simply walking better and somehow becoming speedy runners, our ancestors had to accumulate changes one step at a time. Running was not just a byproduct of standing tall; it demanded its own unique tweaks to muscles and bones.

The evolutionary story of running

Studies that model ancient skeletons like Lucy offer a peek at how our capabilities evolved. By combining insights from fossils, simulations, and knowledge of modern muscle mechanics, scientists can understand how each piece of the puzzle fits together.

The findings not only confirm that Lucy’s species lacked the running power of modern humans, they also highlight where in our evolutionary story those extra boosts emerged.

The research reminds us that our ability to run long and hard is not an accident – it is the product of millions of years of subtle, meaningful changes.

While Lucy’s top running speed and endurance might seem modest, she represents an earlier chapter in a long series of refinements.

By the time we arrived on the scene, we had the legs and lungs for distance. Though our modern world no longer requires daily runs to survive, the natural gift is still built into our bodies, waiting to be used.

The study is published in the journal Current Biology.

Video Credit: Current Biology (2024)

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–