Left behind: Underrepresentation in research puts women, minorities at risk

Left behind: Underrepresentation in research puts women, minorities at risk. Read enough published research and you’ll start to see familiar phrases about how “the study results are limited” or “no definite conclusions can be drawn,” and it turns out that these caveats are crucial.

A study’s results are typically limited due to a finite sample size that is by no means fully representative of the entire population. In other words, the number of people participating in the study does not accurately represent the diverse population of an area.

You’ve probably seen news headlines that read “6 out of every 10 men…” or “4 out of 5 children are at risk of…” or “60 percent of American couples fight over…” as the major takeaways from published research.

But how many people participated in the study in the first place? If the researchers surveyed 10 children in total, 4 out of 5 is probably not an accurate conclusion. Left behind: Underrepresentation in research puts women, minorities at risk

But beyond sample size, there’s another huge problem that plagues many studies: the underrepresentation of marginalized groups in scientific research.

In everything from relationship studies to heart disease risk assessments to clinical trials, researchers time and time again have come short of fully representing a population. And when you’re dealing with sweeping associations, new treatments, prescription dosages, and underlying factors, underrepresented sample sizes matter.

Obvious examples can be drawn from psychological studies dealing with relationships. Whether consciously or not, these studies show an implicit bias favoring heterosexual couples and cisgendered individuals while excluding sexual minority couples.

One 2015 study reviewed a decade worth of relationship research spanning from 2002 to 2012. But of all the articles analyzed, 88.7 excluded sexual minority couples.

“Although there has been a positive trend in the use of inclusive terminology (i.e., partner, significant other) our data suggests that the inclusion of LGB couples in relationship research has not improved in the last decade,” the researchers wrote. “Implications of these findings and potential reasons as to why same-sex couples may be excluded from research studies on romantic relationships are discussed.”

An earlier 2010 study found that clinical trial research on erectile dysfunction and hypoactive sex disorders used “explicit exclusionary language.”

“It is likely that most gay and lesbian patients are unaware that their sexual orientation is being used as a screening factor for participation in clinical trials,” the researchers of that study wrote. “Researchers should be held to careful scientific reasoning when they develop exclusion criteria that are based on sexual orientation.”

There are countless reasons why exclusion and bias negatively impact the LGTBQIA+ community. For one, research can help inform policies, but if little unbiased research exists, policymakers can easily implement laws that further subjugate and harm marginalized groups.

Take the debate that centered around the bathroom rights of transgender individuals. A widespread mass of misinformation, bias, and prejudice only further isolated a community of individuals looking for safer places and for society to more openly accept their identities.

Besides policy that could help break down prejudice, excluding and underrepresenting marginalized groups in research can also adversely impact physical health and mental well-being.

LGTBQIA+ individuals have a higher risk of developing a sexually transmitted disease, being a victim of sexual violence, physical, financial, and emotional abuse, and have a higher risk of suicide or developing an emotion or mood disorder due to social stigmas still very much in existence today.

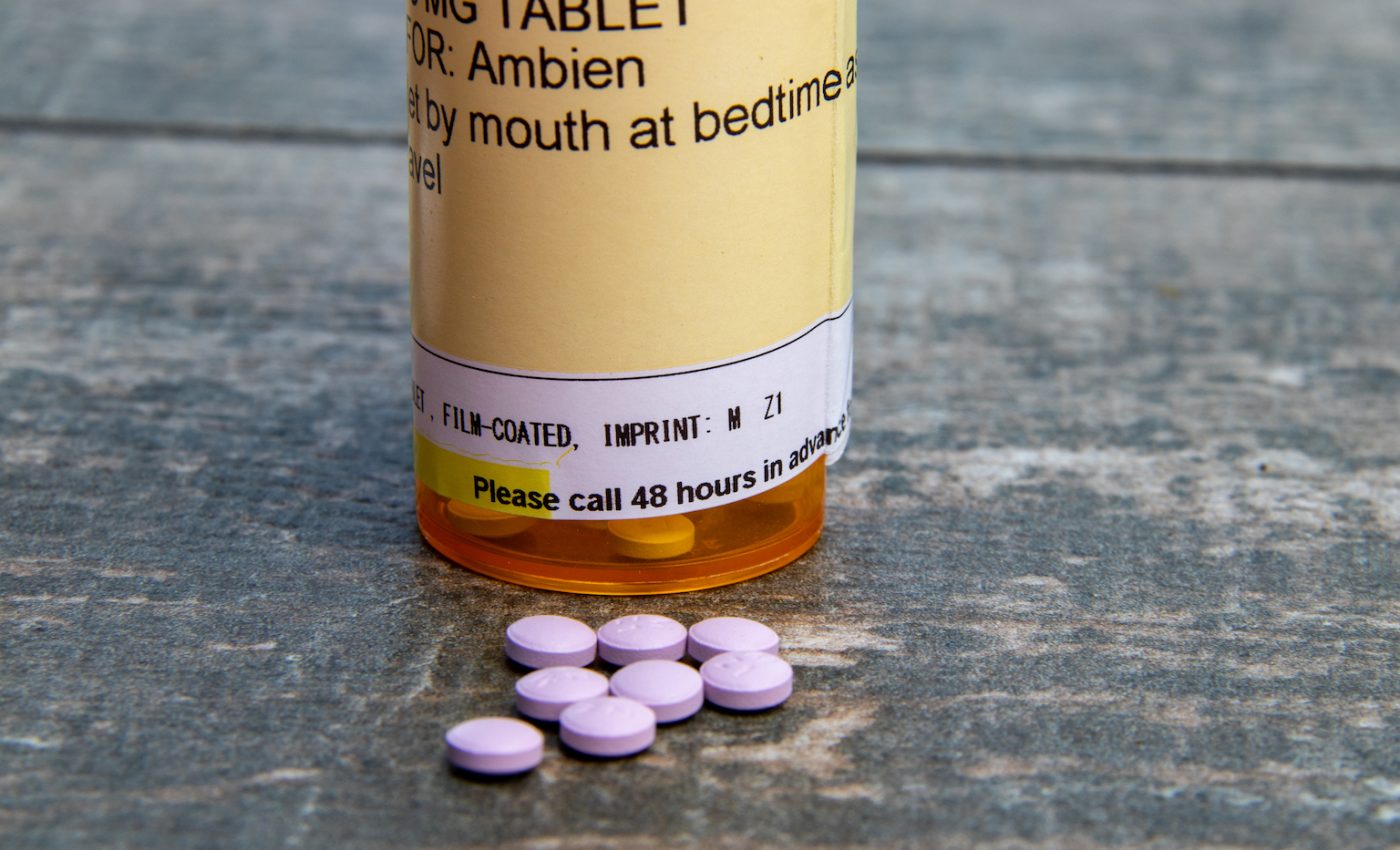

If you want proof that underrepresentation can be dangerous, look no further than the dosage recommendations for the drug Ambien.

In 2013, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced that the proper dosage of any drug containing the ingredient zolpidem for women should be half what was previously recommended.

After years of complaints and around 700 reports of car accidents due to taking Ambien or a similar sleep aid the night before, the FDA conducted a series of lab and driving tests that showed that women metabolize zolpidem slower than men.

Why did it take so long for the FDA to change the recommended dosage? There is a long history of women being underrepresented in scientific research and drug trials.

“This is not just about Ambien — that’s just the tip of the iceberg,” said Dr. Janine Clayton, director for the Office of Research on Women’s Health at the National Institutes of Health told the New York Times. “There are a lot of sex differences for a lot of drugs, some of which are well known and some that are not well recognized.”

Women metabolize drugs differently but only recently have researchers started to explore these differences and understand the negative and dangerous impacts from previously limited sample sizes that excluded women.

It wasn’t until 1993 that the FDA lifted a ban excluding women of childbearing age from participating in new drug trials.

In an article titled “The Drug-Dose Gender Gap,” Rony Caryn Rabin reported that from 1997 to 2000, eight out of ten drugs that were removed from the market were done so because of the increased risks posed to women.

“The path to a new drug starts with the basic science — you study an animal model of the disease, and that’s where you discover a drug target,” Kathryn Sandberg, director of the Center for the Study of Sex Differences in Health, Aging and Disease at Georgetown told Rabin. “But 90 percent of researchers are still studying male animal models of the disease.”

Women have been routinely left out of clinical trials, but exclusion and underrepresentation of people of color in scientific research continues to be a rampant issue.

In 1993, Congress passed the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act in an effort to make sure drug trials would be more diverse and inclusive.

However, one 2014 study conducted by researchers from the University of California Davis found that less than five percent of cancer trial participants were not white and even fewer studies and trials focused on people of color.

When drug trials exclude minorities, not only is it dangerous for prescription dosages, but it also prevents people of color from receiving potentially helpful treatments.

While there are improvements being made in health studies and clinical drug trials, these small steps in the right direction are little consolation to the people who have been further stigmatized, injured, unknowingly put at risk, or barred from treatment through exclusion and underrepresentation in research.

—

By Kay Vandette, Earth.com Staff Writer

Image Credit: Arne Beruldsen / Shutterstock