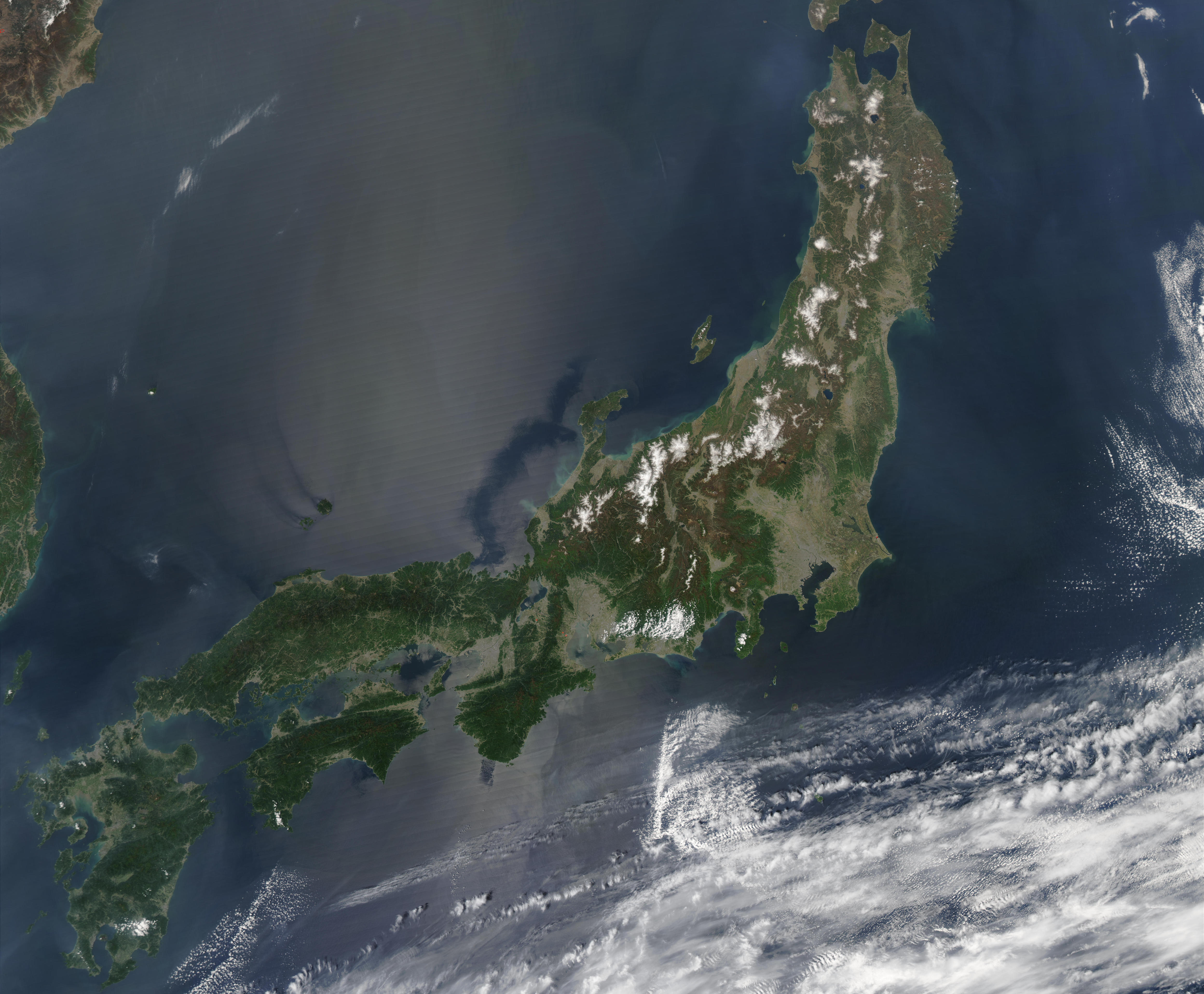

Which parts of Japan are most at risk of a tsunami?

A new GPS-based method that can model tsunamis could help coastal areas in Japan better prepare for potential disaster.

Following the catastrophic 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, the Japanese government asked for hazard assessment research that would identify the worst case scenarios for both earthquakes and tsunamis for the country.

Researchers Hannah Baranes and Jonathan Woodruff from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, along with colleagues from Smith College and the Japanese Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, conducted a study hoping to model potential tsunamis along the Nankai Trough.

“The government guideline has focused attention on the Nankai Trough,” said Baranes. “It’s a fault offshore of southern Japan that is predicted to generate a magnitude 8 to 9 earthquake within the next few decades.”

According to the research, a Nankai-induced tsunami could displace four times the number of people impacted by the 2011 tsunami.

Modeling tsunamis based on potential seismic events would help show the kind of damage and flooding to expect if an earthquake in the region were to occur.

First, the researchers collected sediment cores in Japan so that they could create a long-term record of tsunami flooding.

Marine sediments get trapped within the lake bed as tsunamis flood coastlines, and the researchers looked for evidence of marine sediments with the samples they collected.

“These sand deposits get trapped and preserved at the bottoms of coastal lakes,” said Baranes. “We can visit these sites hundreds or even thousands of years later and find geologic evidence for past major flood events.”

Sediments from Lake Ryuuou, a lake on an island in the Bungo Channel, had a layer of sand that came from seawater that flooded into the lake, making its way over a 13 foot-high barrier.

The flooding corresponds with a Nankai Trough tsunami that occurred in 1707, but the location of the island within the Bungo Channel makes such high flooding unlikely and presented a major challenge for the modeling efforts.

The researchers had to find a way to create a model that simulated an event similar to the 1707 event. If a Nankai-induced earthquake had reached there before, the island was at risk in the event of another Nankai Trough earthquake.

At first, the models and scenarios created tsunamis that were only six-feet high, not nearly enough to breach the 13-foot high barrier.

The researchers then turned to Jack Loveless, a professor at Smith College who uses GPS measurements of earth surface motion and who helped create earthquake scenarios based on GPS estimates of plate movement and frictional locking along the Nankai Trough.

The GPS measurements created a similar scenario to the 1707 earthquake.

“Our model earthquake scenarios showed the Bungo Channel region subsiding seven feet and lowering Lake Ryuuoo’s barrier beach from 13 to six feet, such that a tsunami with a feasible height for an inland region easily flooded the lake,” said Baranes.

The results of the study are promising and potentially could be used to help model future tsunamis in high-risk coastal areas worldwide.

—

By Kay Vandette, Earth.com Staff Writer