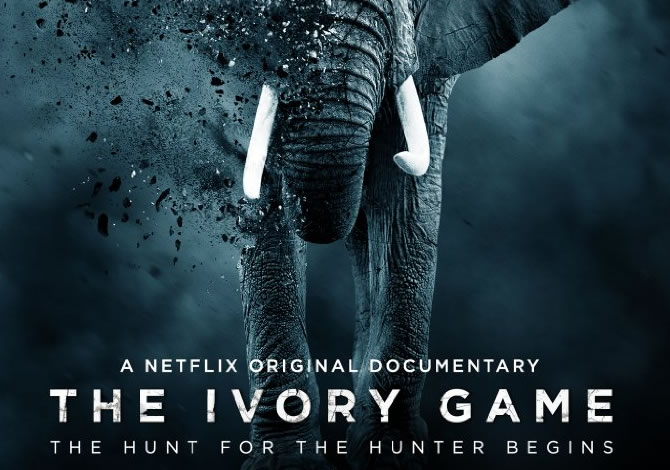

'The Ivory Game' reveals the real cruelty of the ivory trade

Netflix’s The Ivory Game feels like a fast-paced thriller, but unfortunately the stakes are all too real in this documentary that provides an uncomfortably close look at the world’s ivory trade.

Directed by Richard Ladkani and Kief Davidson, the film starts with a midnight raid in Tanzania as police led by Elisifa Ngowi, the head of intelligence for an anti-poaching task force, are looking for Shetani, a notorious poacher.

We hear a voiceover say “Shetani-the devil has taken over,” while a scene of police interrogating suspected elephant killers unfolds. The camera crew is up close and personal and it feels more akin to an episode of Cops rather than a documentary about elephant poaching.

Africa’s elephant populations have been steadily declining due to poaching and habitat loss. During the opening credits of the Ivory Game, we are given a few key facts to help set the tone for the film.

“Over the past five years, more than 150,000 elephants have been killed for their ivory. With populations in western and central Africa virtually gone, the mass killing is now spreading to east and southern Africa.”

When the ivory is smuggled into China, it becomes part of a multi-billion dollar trade that could result in the extinction of elephants in the next 15 years.

The Ivory Game provides a glimpse of almost all the elements of the ivory trade and the fight to stop poaching.

Craig Miller, Head of Security at the Big Life Foundation, speaks to the camera in hushed tones as he follows the elephant “One Ton” whose tusks contain 70 to 80 kilos of ivory.

With Miller, we learn that the job of protecting elephants in Africa is a dangerous one. The poachers are not only willing to risk their lives to kill an elephant but will also shoot at humans who get in their way.

The documentary crew travels from Africa to Beijing, and the audience is shown intricately carved ivory statues, artwork, tusks, and figurines priced at hundreds of thousands of dollars.

It’s in China where we’re introduced to Andrea Crosta, the head of the investigation of an organization called Wildleaks, which is working to gain intel into poaching operations through an online platform where people can report tips anonymously.

From Costa, we learn that ivory is legal in China, but the government only distribute a small amount of ivory each year.

This has opened to the door to rampant smuggling and has made it easy for sellers to sell illegally smuggled ivory. It’s a fact that buyers, consumers, and collectors are either oblivious to or happily ignore in search of precious ivory.

The Ivory Game spares no gruesome detail showing recently slaughtered elephants, stacks and stacks of raw ivory, and unfortunately, extinction seems to be the end goal. No more elephants means that ivory can be priced as high as a seller wants and people will buy.

Much of the Ivory Game follows the hunt for Shetani, a cruel and notorious poacher who has succeeded in evading capture by the police. However, the ivory war expands far beyond the borders of Africa and China.

Hongxiang Huang, a Chinese activist and investigative journalist, takes part in many dangerous undercover operations in Africa, China, and Vietnam to gather information and video footage of illegal ivory trade operations.

In an interview, Huang explains that there are a lot of misconceptions about the “good guys and bad guys” in the ivory war.

When people hear about poaching in Africa, it’s easy to assume that local poachers are the bad guys, the Chinese buyers are the “really bad guys,” and the white people are the heroes, Huang explains.

The Ivory Game attempts to break down these misconceptions head on and show the hard work being done globally to stop poaching on all sides. Local police investigations, conservation efforts, elephant tracking, and undercover sting operations all illustrate how buyers and traders are selling illegal ivory and gaming the system.

The film also reveals that sometimes the matter of killing elephants has nothing to do with the ivory itself.

In one tension-fraught scene, Miller and his team are working to calm a mob of angry farmers.

The farmers are tired of the elephants crossing into their property, eating their crops and essentially trampling over their livelihoods.

One farmer yells, “this is for my children not elephants,” and the line becomes less clear.

Miller brokers a deal with the farmers saying that he will work with them to build a fence to help keep wildlife out, but even a solution as simple as a fence requires tireless hours of fundraising and campaigning.

Both China and the US have announced ivory bans, but the fight is far from over. It’s estimated that around 55 elephants are killed each day for their ivory, according to the World Wildlife Fund.

These vulnerable giants remain in dire need of conservation and protection, and unless more is done to protect elephant populations and their habitats, elephants could be completely wiped out.

—

By Kay Vandette, Earth.com Staff Writer