Why viewing past human populations as separate branches can be misleading

Why viewing past human populations as separate branches can be misleading. The authors of a new study propose that viewing past human populations as a progression of separate or distinct branches on an evolutionary tree may be misleading because it reduces the human story to a series of “splitting times” that is unrealistic. According to the experts, the quest to pinpoint a single location for the origin of modern humans is basically a wild goose chase.

Study lead author Dr. Eleanor Scerri is an archaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and heads the Pan-African Evolution Research Group.

“People like us began to appear sometime between 500,000 and 300,000 years ago,” said Dr. Scerri. “That is something in the order of 8,000 generations, a long time for early people to move around and explore a big space. Their movements, patterns of mixing and genetic exchanges are what gave rise to us.”

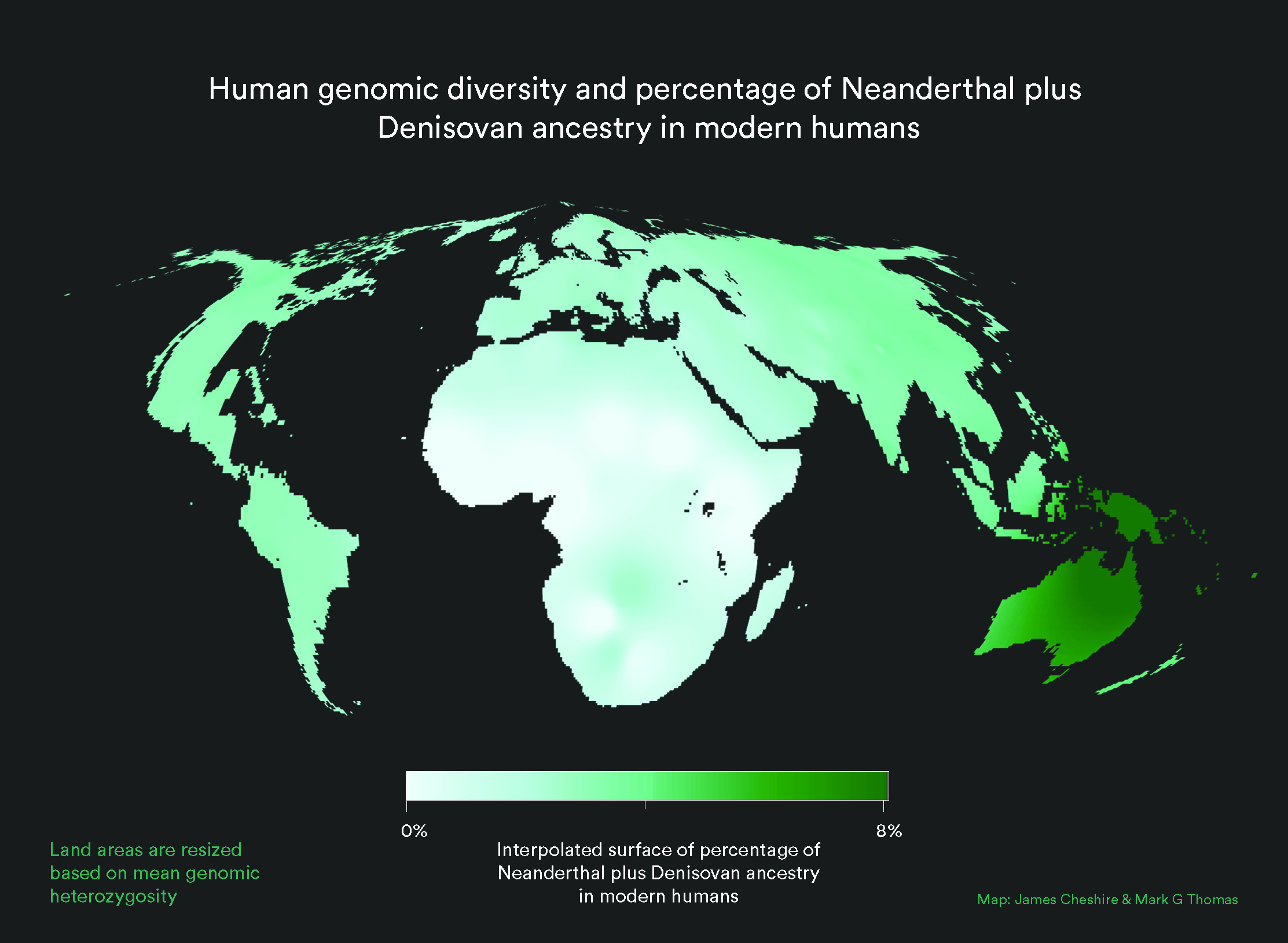

Professor Mark Thomas of University College London explained that the genetics of modern humans is very clear, with the greatest genetic diversity found among Africans.

“The old theory that we descend from regional populations spread across the Old World over the last million years or so is not supported by genetics data. Sure, non-Africans today have some ancestry from Neanderthals, and some have appreciable ancestry from the recently discovered Denisovans. And maybe other, as yet undiscovered ancient hominin groups also interbred with us, Homo sapiens. But none of this changes the fact that more than 90% of the ancestry of everybody in the world lies in Africa over the last 100,000 years,” said Professor Thomas.

“The problem is that knowing that we are an African species has led many to ask the question ‘where in Africa.’ Superficially this is a reasonable question. But when we consider the genetic patterns alongside what we know of fossils, ancient tools, and ancient climates, the ‘single region of origin’ view just doesn’t cut it, and we have to start thinking differently. This means different models, and we argue in the current paper that structured population models are the way forward.”

Dr. Lounès Chikhi of the University of Toulouse explained that the interpretation of the available data changes when it is viewed through the lens of dynamic changes in connectivity, or metapopulations.

“Instead of a series of population splits branching off an ancestral tree, changes in connectivity between different populations over time seem a more reasonable assumption, and appear to explain several patterns of genomic diversity not explained by current alternative models,” said Dr. Chikhi.

“Metapopulations are the kind of model you’d expect if people were moving around and mixing over long periods and wide geographic areas. We cannot objectively identify this geographic area today from genetic data alone, but data from other disciplines suggest that the African continent represents the most likely geographical scale.”

The scientists argue that viewing the human story as a “dynamic interconnected patchwork of populations” is better supported by the fossil, genetic, and archaeological evidence. In addition, this approach better explains the palaeoanthropological record beyond Africa.

“We see physically diverse early human fossils from across Africa, some very old genetic lineages and a pan-African shift in technology and material culture that reflects advanced cognition, including new technical and social innovations, across the continent. In other words, what you’d expect from a dynamic interconnected patchwork of populations that were at times more or less isolated from each other,” said Dr. Scerri. “This would also help to explain the increasing evidence for unexpected populations, including in areas outside Africa such as the Hobbits on Flores.”

The study authors emphasize that what this really means is that the scientific community may finally have the means to address complex questions in human evolutionary studies that could not be addressed previously.

“We have so much new data now from genetics, archaeology and fossils, and a better understanding of how past climates and environments affected early people. We have come to a point where the old models are constraining progress in our understanding of the past,” said Dr. Chikhi.

“A metapopulation model helps us to find a way to acknowledge the paleontological, archaeological and genetic evidence for a recent African origin with limited gene flow from non-African metapopulations, such as Neanderthals, without falling into overly polemic and restrictive debates,” added Dr. Scerri.

“Our African origins cannot be denied, but we definitely don’t yet have the resolution to include or exclude different bits of evidence simply because they don’t fit with a particular view. We need better reasons than that.”

Professor Thomas suggested that the human record starts to make a lot more sense when studied from the perspective of changes in connectivity.

“We need such flexibility to be able to make sense of the past, or we get lost in a malaise of ever-increasing named species, failed trajectories and population trees that never existed,” said Professor Thomas. “Science always favors the simpler explanation and it is becoming increasingly difficult to stick to old narratives when they have to become over-complicated in order to stay relevant.”

The study is published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

—

By Chrissy Sexton, Earth.com Staff Writer

Image Credit: Shutterstock/robuart