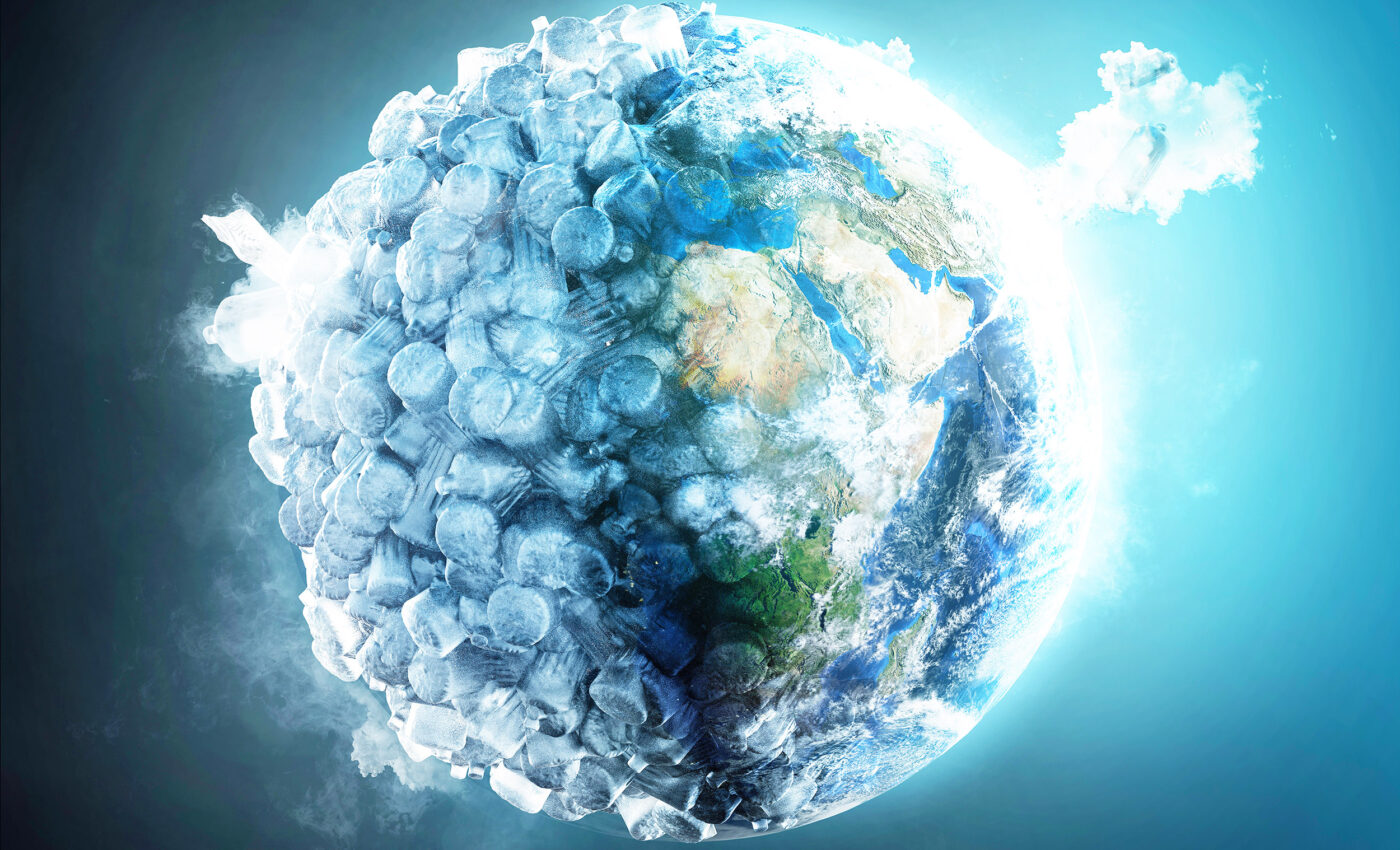

Global plastics treaty tackles the pollution problem directly at the source

In Nairobi, Kenya, the pulse of environmental policy beats with renewed urgency as delegates from around the world convene for the third International Negotiation Committee meeting (INC-3). The conference is a pivotal step toward formulating a legally binding global plastic pollution treaty.

This ambitious endeavor seeks not merely to stem the tide of plastic pollution but to confront it at its very source.

Tackling plastic pollution at the source

A new study illuminates the path forward, as noted by environmental experts. A legally binding, global treaty must transcend traditional waste management strategies.

The researchers advocate for a decisive shift towards “upstream” interventions. These are strategies that reduce the total production and consumption of plastics, phase out hazardous chemicals integral to their manufacture, and address the subsidies that bolster the fossil fuel industry, which is the bedrock of plastic production.

The prevailing focus on “downstream” recycling and waste management, while integral, is deemed insufficient by the scientific community.

Dr. Mengjiao (Melissa) Wang of the Greenpeace Research Laboratories at the University of Exeter criticizes the disproportionate investment in recycling and cleanup efforts. She asserts they are akin to “removing the mess while making more.”

An effective treaty must be holistic, encompassing the entire spectrum from fossil fuel extraction to waste disposal.

Barrier to upstream innovations

Current investment strategies reveal a stark imbalance, with 88% of funds directed toward recovery and recycling and a paltry 4% allocated to upstream reuse solutions. This disparity is rooted in a political economy deeply entangled with the fossil fuel industry, which continues to accelerate plastic production and exacerbate the triple Planetary Crisis: climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution.

The zero draft of the treaty, while a starting point, is criticized for its heavy emphasis on waste management. It sidelines more efficient and cost-effective upstream strategies such as reduction, redesign, and reuse.

The study claims that the draft could be strengthened by imposing fees on polymer manufacturers based on the volume of primary plastics produced. This would foster strong Extended Producer Responsibility schemes, and ensuring financial mechanisms prioritize upstream strategies.

Closing the “back door”

As global climate governance grapples with the cessation of burning fossil fuels, the Plastics Treaty emerges as a critical instrument to prevent these same fuels from being repurposed into plastics. This is an unfortunate loophole left by the Paris Agreement. Dr. Lucy Woodall from the University of Exeter highlights the treaty’s potential to seal this “back door.”

“The problem of plastic pollution is huge, and it can feel overwhelming,” said Dr Woodall. “But there are opportunities and challenges at each stage of the life cycle of plastics – from fossil fuel extraction onwards.”

The treaty must also champion ecosystem health and equity, emphasizing the restoration of natural systems disproportionately burdened by plastic pollution. The simplification of chemicals in plastics is another critical area, demanding heightened transparency and traceability from producers to ensure the safe recycling of products.

Political and scientific balancing act

Despite the aspirational nature of the treaty, resistance from certain nations is anticipated. The challenge for negotiators lies in reconciling political feasibility with the ambitious scope necessary to address the crisis comprehensively. Scientists like Dr. Wang play a crucial role, offering a “scientific reality check” to ensure that the treaty aligns with the planet’s ecological boundaries.

As negotiations forge ahead, the global community stands at a crossroads. The outcome of the Plastics Treaty could mark a transformative step in how the world addresses plastic pollution.

With a holistic and ambitious approach, there is hope that the treaty will catalyze a shift towards a sustainable future, where the health of ecosystems and the well-being of communities are at the forefront of global environmental policy.

More about plastic pollution

Plastic pollution represents one of the most pressing environmental issues of our time. The durability of plastic, which once heralded it as a miracle material, now curses the landscapes, waterways, and oceans of the world. Every year, millions of tons of plastic end up in the ocean, breaking down into microplastics that permeate marine ecosystems and enter the food chain.

Life cycle of plastic

Manufacturers produce plastic from fossil fuels, and its life cycle begins with extraction. From there, industries shape it into countless products, many designed for single use.

After serving its short-term purpose, plastic embarks on its long-term environmental impact, with much of it ending up as waste. Disposal practices vary, but recycling rates remain dismally low, and large quantities of plastic waste find their way into the environment.

Consequences of plastic waste

Plastic waste ravages ecosystems, entangles wildlife, and introduces toxic substances into the environment. Microplastics, the degraded remnants of larger items, now pervade the most remote corners of the planet. These tiny particles carry pollutants and pose a significant threat to aquatic life and human health.

Tackling plastic pollution

As discussed above, in order to tackle plastic pollution, we must adopt a multi-faceted approach. This means reducing production, enhancing recycling, and rethinking our relationship with plastic. Governments, corporations, and individuals all hold responsibility for initiating and supporting these critical changes.

Policy and regulation

Effective policy and regulation play vital roles in combating plastic pollution. Bans on single-use plastics, incentives for recycling, and funding for research into alternative materials can drive down plastic waste.

Policies must also target the reduction of plastic production and encourage the development of circular economies where products and materials maintain their value and remain in use for as long as possible.

Technological innovation and recycling

Advancements in technology offer hope for improved recycling processes and the creation of biodegradable and compostable alternatives. However, these technologies must scale up and become economically viable. Furthermore, recycling systems require enhancement to handle the complexity and volume of plastic waste generated globally.

Public education and behavioral change

Educating the public about the impact of plastic pollution and how to reduce personal plastic waste is crucial. Behavior change campaigns can encourage consumers to choose reusable options, support environmentally friendly products, and participate in community clean-up efforts.

Corporate responsibility and sustainable design

Companies must adopt sustainable design principles, minimizing the use of plastic where possible and ensuring products are recyclable at the end of their life. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes can hold manufacturers accountable for the environmental impacts of their products, from design to disposal.

Global plastic pollution collaboration

As discussed previously, combating plastic pollution requires global collaboration. International agreements, like the proposed global Plastics Treaty, can set ambitious targets and unify global efforts.

Through collective action, the international community can implement effective strategies to mitigate the impact of plastic pollution and safeguard the planet for future generations.

In summary, plastic pollution demands urgent and sustained action. By embracing innovation, enacting robust policies, fostering behavioral change, and encouraging corporate responsibility, we can forge a path towards a less polluted, more sustainable world.

The full study was published in the journal Science.

—

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

—

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.