Glass particles in Hiroshima beach sand are fallout debris

Career geologist Mario Wannier has identified tiny glass particles found in beach sands near Hiroshima, Japan as fallout debris from the atomic bomb that hit the city on August 6th, 1945. His study of the particles, published in the journal Anthropocene, likens the particles to those left over from massive meteorite strikes.

“I had seen hundreds of beach samples from Southeast Asia, and I can immediately distinguish mineral grains from the particles created by animals or plants, so that’s very easy,” he said. “But there was something else…it’s so obvious when you look at the samples,” Wannier said of the glassy particles found in the sands of Japan’s Motoujina Peninsula, located near Hiroshima. “You couldn’t miss these extraneous particles.”

“They are generally aerodynamic, glassy, rounded — these particles immediately reminded me of some spherule (rounded) particles I had seen in sediment samples from the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary,” Wannier continued, in reference to the mass-extinction event that killed off the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. The Cretaceous-Tertiary (K-T) boundary is now referred to as the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary.

A meteorite impact, such as the one that occurred during the K-Pg boundary, causes liquified ground material to launch into the air, which are formed into glassy droplets during the explosion. However, Wannier noted that the particles found near Hiroshima were slightly different than those that were made during the K-Pg boundary. Some Hiroshima particles had a rubber-like composition, and others were coated in silica or glass.

Particles collected from beach sands in Japan’s Motoujima Peninsula. Image Credit: Anthropocene, Volume 25, March 2019

Together with researchers from Berkeley Lab and The University of California, Berkeley, Wannier was able to determine that these particles were created during the A-bomb hit, which leveled a 4-square mile area of land and destroyed and damaged about 90% of Hiroshima’s infrastructure.

“This was the worst manmade event ever, by far,” Wannier said. “In the surprise of finding these particles, the big question for me was: You have a city, and a minute later you have no city. There was the question of: ‘Where is the city — where is the material?’ It is a trove to have discovered these particles. It is an incredible story.”

The team first looked at the structures and compositions of the particles using an electron microscope. Some particles contained aluminum, silicon and calcium, chromium-rich iron, and microscopic branching of crystalline structures. Others contained mostly carbon and oxygen.

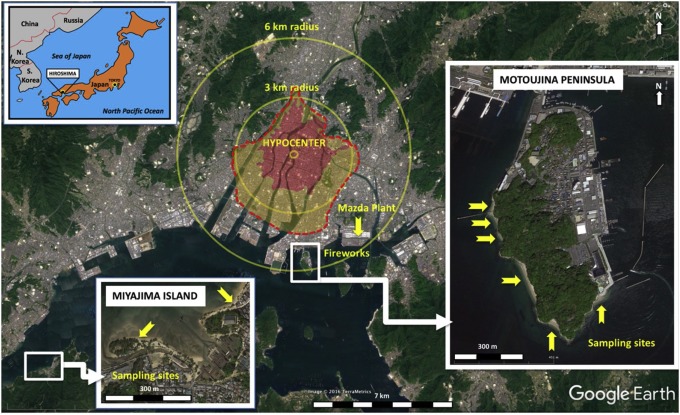

Sites where beach sands were collected and the area that was devastated by the Hiroshima atomic bomb.

Image Credit: Google Earth; Anthropocene, Volume 25, March 2019

They then measured the particles using X-ray microdiffraction. Together, the findings told Wannier that the particles had formed in extreme conditions, at temperatures exceeding 3,300 degrees Fahrenheit. They were most likely formed within the atomic cloud.

“The ground material is volatized and moved into the cloud, where the high temperature changes the physical condition,” Wannier explained. “There are a lot of interactions between particles. There are lots of little spheres that collide, and you get this agglomeration.”

The team hopes to carry out studies to determine if these particles contain radioactive elements.

—

By Olivia Harvey, Earth.com Staff Writer