Galaxies in the deep universe all rotate in the same direction, leaving scientists baffled

The universe is full of surprises, with each new discovery reshaping our understanding and offering astonishing new perspectives on space objects such as galaxies.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), launched just over three years ago, has already exceeded expectations. It peers deep into space, revealing galaxies from the dawn of time and answering questions once thought impossible.

A recent study from Kansas State University has revealed something strange. The way galaxies rotate isn’t as random as scientists once believed.

Instead, JWST images suggest a hidden pattern – one that challenges fundamental assumptions about the cosmos.

Most galaxies spin the same way

Lior Shamir, an associate professor of computer science at Kansas State University, examined images from the JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES).

His research focused on spiral galaxies and the direction in which they rotate. Logically, their spin should be evenly distributed. Half should turn one way, half the other – but that is not what Professor Shamir found.

Out of 263 galaxies with clearly identifiable rotation, about two-thirds spun clockwise. The remaining third rotated counterclockwise.

This imbalance suggests that the universe might not be as random as we think. It could have a built-in rotation – something baked into its very structure.

The galaxy spin pattern

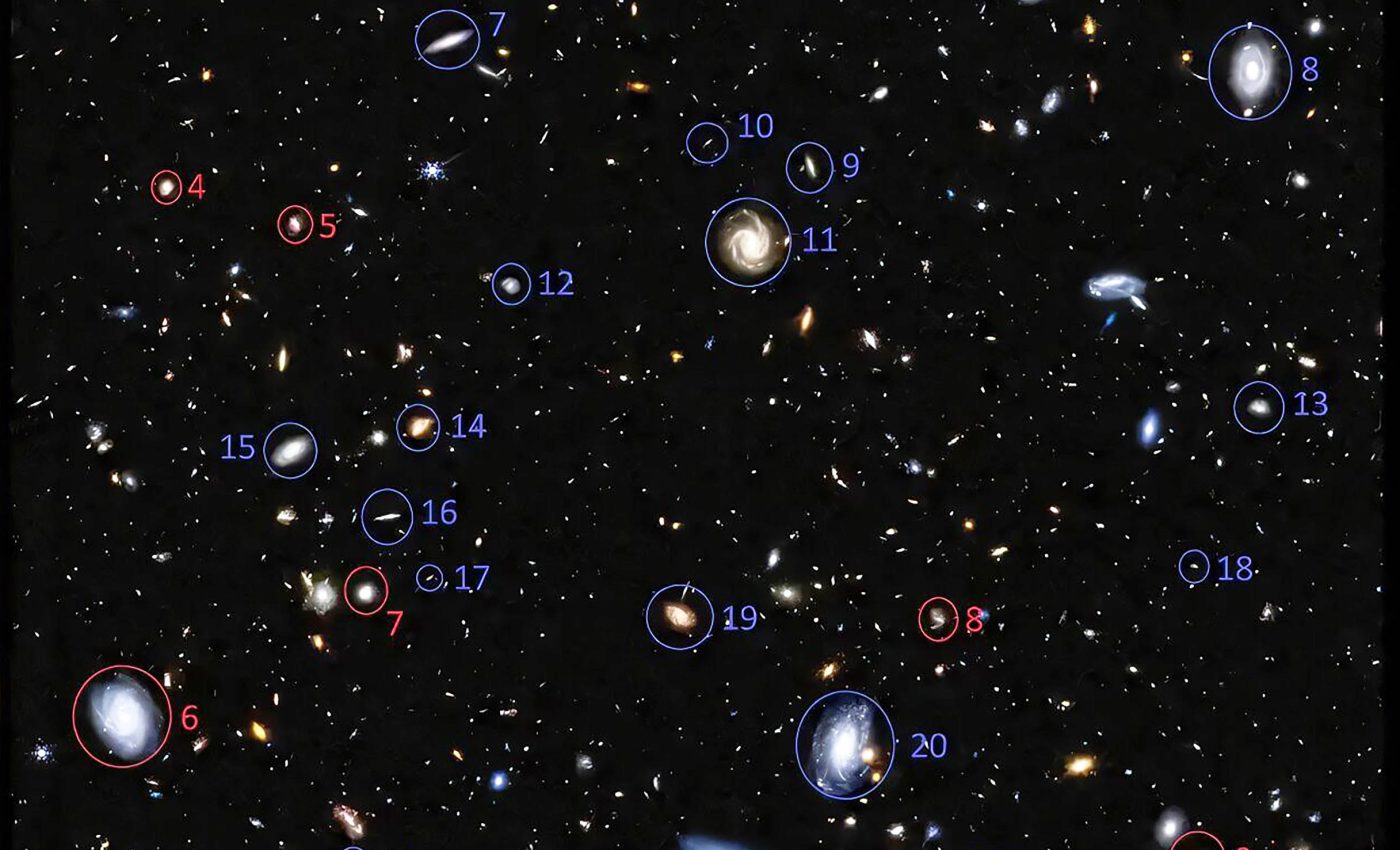

“The analysis of the galaxies was done by quantitative analysis of their shapes, but the difference is so obvious that any person looking at the image can see it,” said Professor Shamir.

“There is no need for special skills or knowledge to see that the numbers are different. With the power of the James Webb Space Telescope, anyone can see it.”

This isn’t a discovery buried in complex equations. No advanced training is needed to spot the difference. The pattern is right there, staring back from the depths of space. That makes the finding even more surprising.

If something so clear has gone unnoticed until now, what else have astronomers missed?

Could the universe itself be spinning?

There are two possible explanations for this anomaly.

The first is radical: the universe itself might have been born spinning. If true, this would support the controversial black hole cosmology theory, which suggests that everything we see exists inside a black hole.

It’s an idea that challenges conventional thinking. But if galaxies across the cosmos follow a consistent rotation, it may not be so far-fetched.

If the universe does have a preferred direction of spin, it would mean something fundamental about physics has been overlooked. The laws governing the cosmos might not be as neutral as we thought.

Instead, they could carry the fingerprint of a primordial motion – one set in place since the very beginning.

Earth’s motion and galaxy spin data

Not all solutions need to be extraordinary. Professor Shamir suggests another, more grounded possibility. The Milky Way itself rotates, and the Earth moves within it.

Because of this motion, light from galaxies spinning in the opposite direction might appear slightly brighter due to the Doppler effect.

If this is the case, JWST’s observations are not revealing a cosmic imbalance. They are simply highlighting an observational bias caused by our own movement through space.

If this explanation holds, it would mean astronomers have been overlooking an important factor when studying deep-space images.

The rotational motion of the Milky Way, once thought too slow to influence observations, could be subtly affecting how we measure light from distant galaxies.

Rethinking distance in the universe

“If that is indeed the case, we will need to re-calibrate our distance measurements for the deep universe,” noted Professor Shamir.

That statement carries enormous implications. If astronomers have miscalculated distances because of unnoticed rotational effects, then our understanding of the universe’s size and structure may need adjustment.

Some galaxies, which appear to be impossibly old under current models, might be much closer than assumed.

This could also help resolve one of cosmology’s biggest puzzles: the conflicting measurements of the universe’s expansion rate.

The Hubble constant, which describes how fast space is stretching, has been the subject of debate for years. Different methods produce different results, leading to what scientists call the “Hubble tension.”

If Shamir’s findings require astronomers to adjust their distance measurements, they might also provide a solution to this longstanding mystery.

Challenging previous assumptions

If the findings hold, the consequences could be enormous. The assumption that the universe has no preferred direction has been a cornerstone of cosmology for decades.

If JWST’s images suggest otherwise, then some of the most fundamental theories about the cosmos may need revision.

More research is needed. Future studies will have to confirm whether this pattern is real or just an illusion created by observational biases.

Other telescopes, both space-based and ground-based, will likely be used to analyze additional galaxies.

If the pattern persists, scientists will have no choice but to rethink how the universe operates.

What happens next?

The James Webb Space Telescope continues to push the boundaries of what we know. Each new observation brings fresh questions.

Professor Shamir’s study is a reminder that even the simplest observations can upend decades of scientific understanding.

If the universe does have a built-in spin, it could change everything we know about cosmic evolution. If the anomaly is due to observational bias, it will still force astronomers to refine their tools and methods.

Either way, one thing is certain: the cosmos isn’t done surprising us yet.

The study is published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–