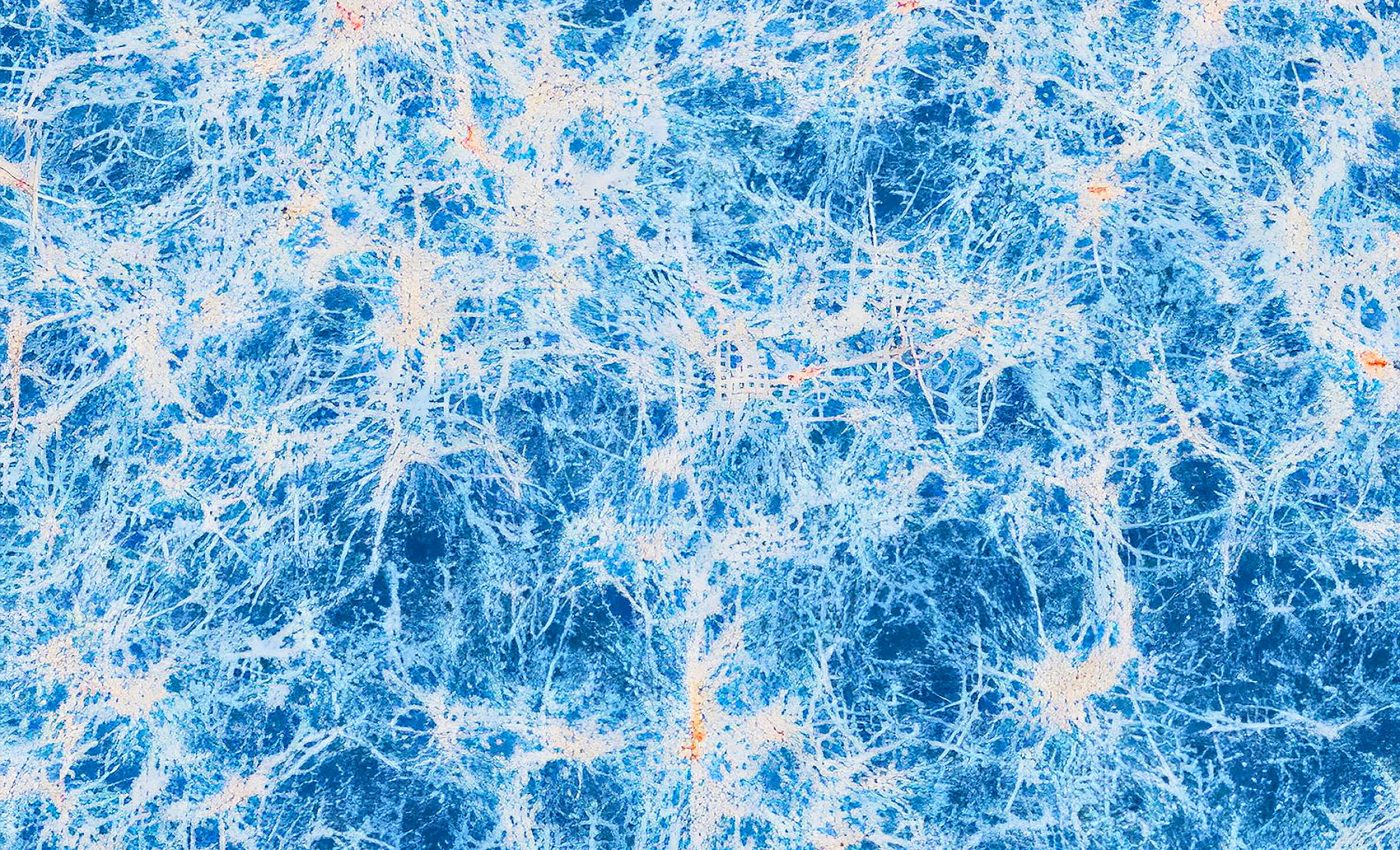

First high-def image of the 'cosmic web' shows hidden universal highways

Galaxies don’t float around at random. They line up along strands of cosmic filaments, sometimes stretching millions of light-years, that shape how stars and other structures form across the universe.

These strands link galaxies in a pattern that astronomers call the cosmic web. By observing this vast network, researchers learn how galactic neighborhoods emerge, grow, and fuel new stars.

Cosmic filament connections

Astronomers have long suspected that this web exists because nearly 85% of all matter in the universe appears to be dark matter, a form of matter that does not interact with light in a direct way.

Computer simulations suggest that this invisible substance gathers into filaments under the pull of gravity.

Gas follows these filaments, feeding galaxies nestled where strands intersect. Until recently, only hints of that gas emerged through absorption signatures.

Detecting the faint glow of the most abundant element, hydrogen, remained a challenge.

This fascinating research was led by Davide Tornotti, Ph.D. student at the University of Milano-Bicocca, in collaboration with the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics (MPA).

High-definition detailed images

A new investigation offered a closer look at a filament linking two galaxies that existed when the universe was about 2 billion years old.

Each galaxy hosts an active supermassive black hole. The team targeted these objects with an instrument named MUSE (Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer) on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile.

They devoted hundreds of hours to gather data from a single region of the sky. This ambitious effort allowed them to capture a detailed picture of a cosmic filament spanning roughly 3 million light-years.

That high-definition image, reported in Nature Astronomy, indicates that the gas forming this strand supplies vital ingredients for star formation.

For the first time, researchers traced its boundary with precise detail.

They confirmed that the gas inside the filament appears to be connected directly to the gas within the host galaxies, illuminating how these immense structures contribute to the evolution of galaxies across cosmic time.

Pinpointing faint light

“By capturing the faint light emitted by this filament, which traveled for just under 12 billion years to reach Earth, we were able to precisely characterize its shape,” explains Tornotti.

“For the first time, we could trace the boundary between the gas residing in galaxies and the material contained within the cosmic web through direct measurements.”

Such clarity reflects the cutting-edge design of MUSE. Its ability to split incoming light into many wavelength channels helps astronomers detect emissions usually lost in the glare of brighter sources.

The study team matched their observations against supercomputer simulations from MPA.

“When compared to the novel high-definition image of the cosmic web, we find substantial agreement between current theory and observations,” Tornotti adds.

Why cosmic filaments matter

These results support the notion that galaxies rely on these filaments for fresh supplies of gas.

The strands appear to be a backbone for how structure arises, guiding both dark matter and regular matter into clusters of stars.

Such conclusions also highlight the synergy between observational campaigns and theoretical models.

The data show that, at least in this case, the shape and density of the gas nearly match what cosmologists predict.

By confirming this match, scientists gain new confidence in their models of how dark matter shapes galaxies.

It also suggests that more discoveries like this one may be around the corner as advanced telescopes refine their methods.

What happens next?

“We are thrilled by this direct, high-definition observation of a cosmic filament. But as people say in Bavaria: ‘Eine ist keine’ – one doesn’t count,” MPA staff scientist Fabrizio Arrigoni Battaia exclaimed.

“So we are gathering further data to uncover more such structures, with the ultimate goal of having a comprehensive vision of how gas is distributed and flows in the cosmic web.”

These words from Battaia highlight the continuing effort to capture the faint glow of additional strands, offering a path to understand how galaxies replenish their star-making material.

Refining this view of large-scale gas networks could reshape our picture of cosmic activity.

By tracing these filaments in different parts of the sky, researchers can confirm whether galaxy formation truly follows the same pattern everywhere.

Each new finding builds on the last, revealing how galaxies maintain and renew themselves. Observers see a chance for deeper insights into the elusive connections that govern the biggest structures known.

Cosmic filaments and future exploration

To sum it all up, high-resolution views of the cosmic web might once have seemed like a distant vision. They are now moving into focus, showing how gas behaves across millions of light-years.

This single observation campaign has sharpened humanity’s understanding of the engine that drives galaxy growth.

It underscores how dedicated, patient efforts can shed light on some of the faintest signals in the cosmos, giving a glimpse into the hidden architecture that shapes everything we see in the night sky.

The full study was published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–