Far side of the Moon had volcanic eruptions for over one billion years

You’ve undoubtedly noticed that the Moon has two distinct sides, right? The near side that we see from Earth and the far side that remains a mystery because it is never turned towards us.

This unusual lunar characteristic — a global dichotomy — is what a team of scientists led by Professor XU Yigang from the Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry (GIGCAS) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has been investigating.

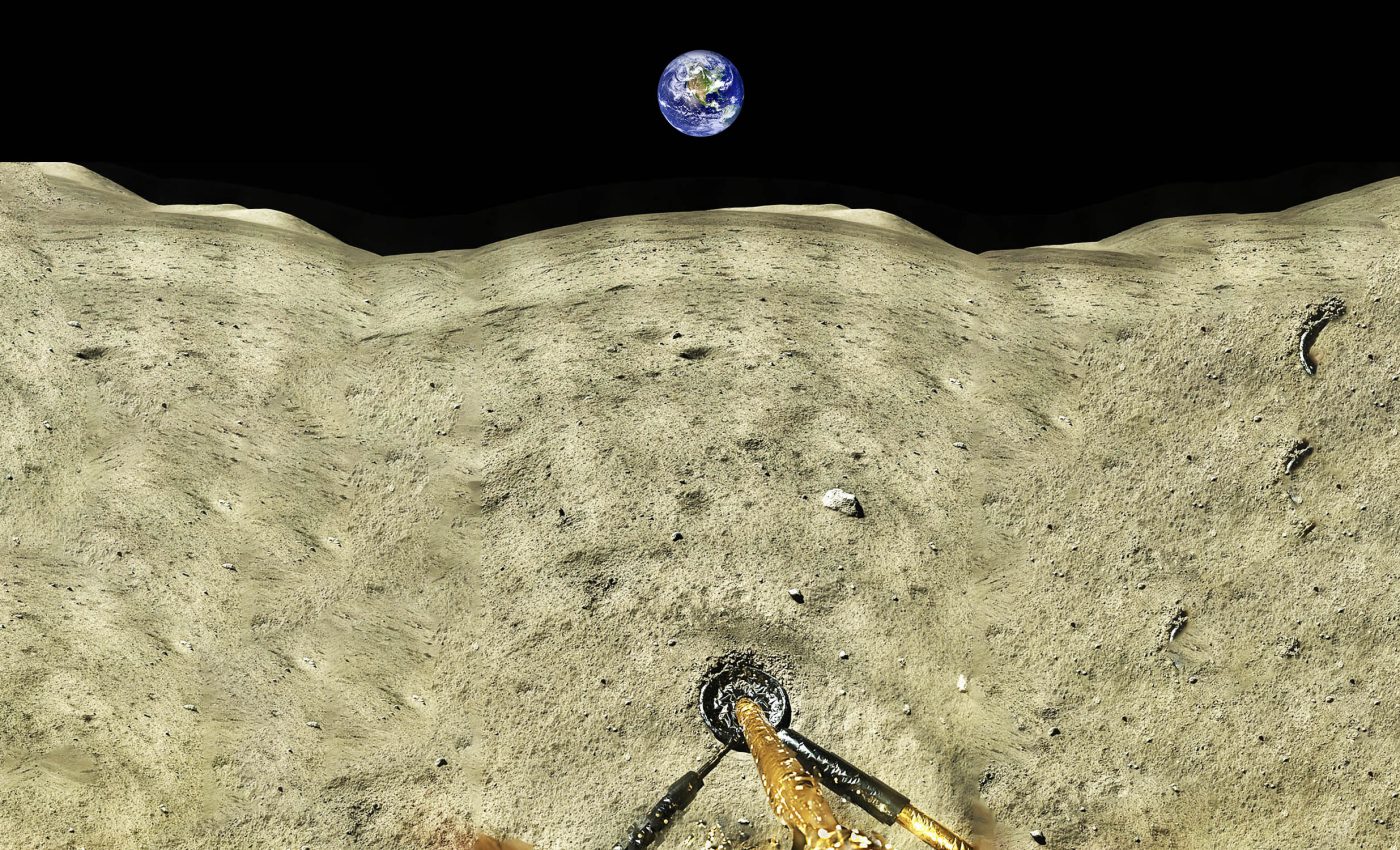

They have been studying lunar soil samples collected from the South Pole-Aitken (SPA) Basin on the far side of the Moon, and returned to Earth by China’s Chang’e-6 mission.

These invaluable samples have allowed them to investigate the Moon’s peculiar dichotomy and the results have shed light on some of its secrets.

What is Chang’e-6?

The Chinese space program launched Chang’e 6, their latest Moon mission, on May 3, 2024. The spacecraft blasted off from Wenchang Satellite Launch Center on a Long March 5 rocket at 9:27 UT (that’s 5:27 PM Beijing time).

Their goal? To grab about four pounds (2 kg) of Moon rocks from the far side – something no one had done before.

The lander touched down in a huge crater called the South Pole Aitken Basin. The team used both a scoop and a drill to dig up surface samples and even went 2 meters deep into the lunar soil.

They also sent out a small rover that cruised around taking snapshots of the lander doing its work.

Once they collected the samples, the crew packed them into an ascent vehicle sitting on top of the lander.

On June 3 at 11:38 PM UT (7:38 AM Beijing time the next day), this vehicle shot up from the Moon’s surface and met up with the orbiter waiting above. They made the handoff on June 6, 2024.

After ditching the ascent vehicle (which crashed back into the Moon), the return vehicle hung around in orbit for a couple weeks before heading home.

It pulled off a tricky skip-entry through Earth’s atmosphere and landed in Inner Mongolia’s Siziwang Banner region on June 25 at 6:07 UT (2:07 PM Beijing time).

The final haul? Roughly 4.2 pounds (1.9 kg) of Moon rocks and soil from the far side — marking another big win for China’s space program.

Far side vs. visible side of the Moon

The Moon’s dichotomy is visible in its topography, chemical composition, crustal thickness, evidence of volcanism and, most noticeably, in the difference in geomorphology between its near and far sides.

The near side of the Moon is home to the familiar “man in the moon” maria – the dark “seas” that are the result of ancient volcanic activity.

These areas were flooded with molten lava that created rocks known as mare basalts.

How about the far side? Well, here’s where it gets intriguing. Only about 2% of this hidden part of the Moon is covered in the basalts, compared to around 30% on the near side.

This inexplicable difference is a vital part of the lunar global dichotomy that the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program aims to unravel.

Secrets of the Moon’s far side

Thanks to the Chang’e-6 lunar soil samples, Professor XU’s team discovered the existence of two different types of mare basalts, low-Ti, and very low-Ti (VLT).

“The samples returned by Chang’e-6 provide a best opportunity to investigate the lunar global dichotomy,” said Professor XU.

Let’s not dismiss the aspect of dating these samples either. With high-precision Pb-Pb dating techniques, the team determined that the low-Ti basalt dates back to around 2.83 billion years ago.

This attests to the presence of “young” magmatism or volcanic activities on the far side of the Moon. But of course, young is a relative term when we talk about 2.83 billion years.

Mapping the history of volcanoes

With such valuable information now in our hands, we can clearly chart the volcanic timeline on the far side of the Moon.

Led by Professor LI Qiuli, the team conducted radioisotope dating on 108 basalt fragments, with 107 of them revealing a consistent formation age of 2807 million years ago.

But there’s more. One fragment, a high-aluminum basalt, was dated to a monumental 4203 million years ago, making it the oldest lunar basalt for which age has been precisely determined.

This implies elevated levels of volcanic activity on the far side of the Moon for at least 1.4 billion years – between 4.2 billion and 2.8 billion years ago.

Why does any of this matter?

These findings, available for everyone to dissect, can help recalibrate the existing lunar crater chronology models.

Christopher Hamilton, an independent planetary volcano expert, emphasized the importance of obtaining samples from this previously unchartered lunar territory.

More than just understanding the Moon, these lunar soil samples also have implications for some broad astronomical theories.

The new data indicates a constant impact flux after 2.83 billion years, which can offer new insights into planet migration in the early Solar System.

So, by looking at the Moon, we are indirectly learning about our own cosmic neighborhood as well!

What happens next?

With more missions like the Chang’e-6, the future will undoubtedly bring many enlightening discoveries about our constant celestial companion.

In the end, we see that the Moon, despite its familiar appearance, still hides untold secrets waiting to be discovered.

These lunar missions represent a new age of lunar and planetary exploration that pushes the boundaries of our understanding.

—–

The researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences express their gratitude for the support received from various institutes such as the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. These institutions’ enduring support enables such important lunar explorations.

The study is published in the journals Nature and Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–