Endangered birds are moving to area where giant moa went extinct

When the mysteries of the past reveal secrets that can aid in preserving the present, it is imperative to take notice. In New Zealand, flightless birds, renowned for their distinctive traits and susceptibility to extinction, are finding sanctuary in regions once inhabited by the now-extinct giant bird, the moa.

Species such as the kiwi and the takahē not only embody a crucial aspect of New Zealand’s natural heritage but also underscore the vital importance of conservation efforts.

By examining the habitats and behaviors of these remarkable birds, researchers can extract valuable insights into the protection and restoration of ecosystems.

How can our understanding of the moa’s legacy and today’s avifauna inform future conservation strategies? Addressing this question is essential for ensuring that these unique species — and the ecosystems they inhabit — thrive for generations to come.

Peeling back the layers of time

At the forefront of this discovery is an international team of dedicated researchers, spearheaded by the esteemed University of Adelaide.

Associate Professor Damien Fordham, a key figure from the University of Adelaide’s Environment Institute, expressed considerable pride and enthusiasm as he unveiled the team’s significant findings.

“Our research has successfully navigated past logistical challenges that often impeded progress in this field, allowing us to trace the population dynamics of six moa species at resolutions previously deemed impossible,” he noted.

This remarkable achievement not only illuminates the ecological history of these intriguing creatures but also opens new pathways for understanding their interactions with the environment and other species throughout their existence.

How might these insights reshape our understanding of biodiversity and conservation efforts today?

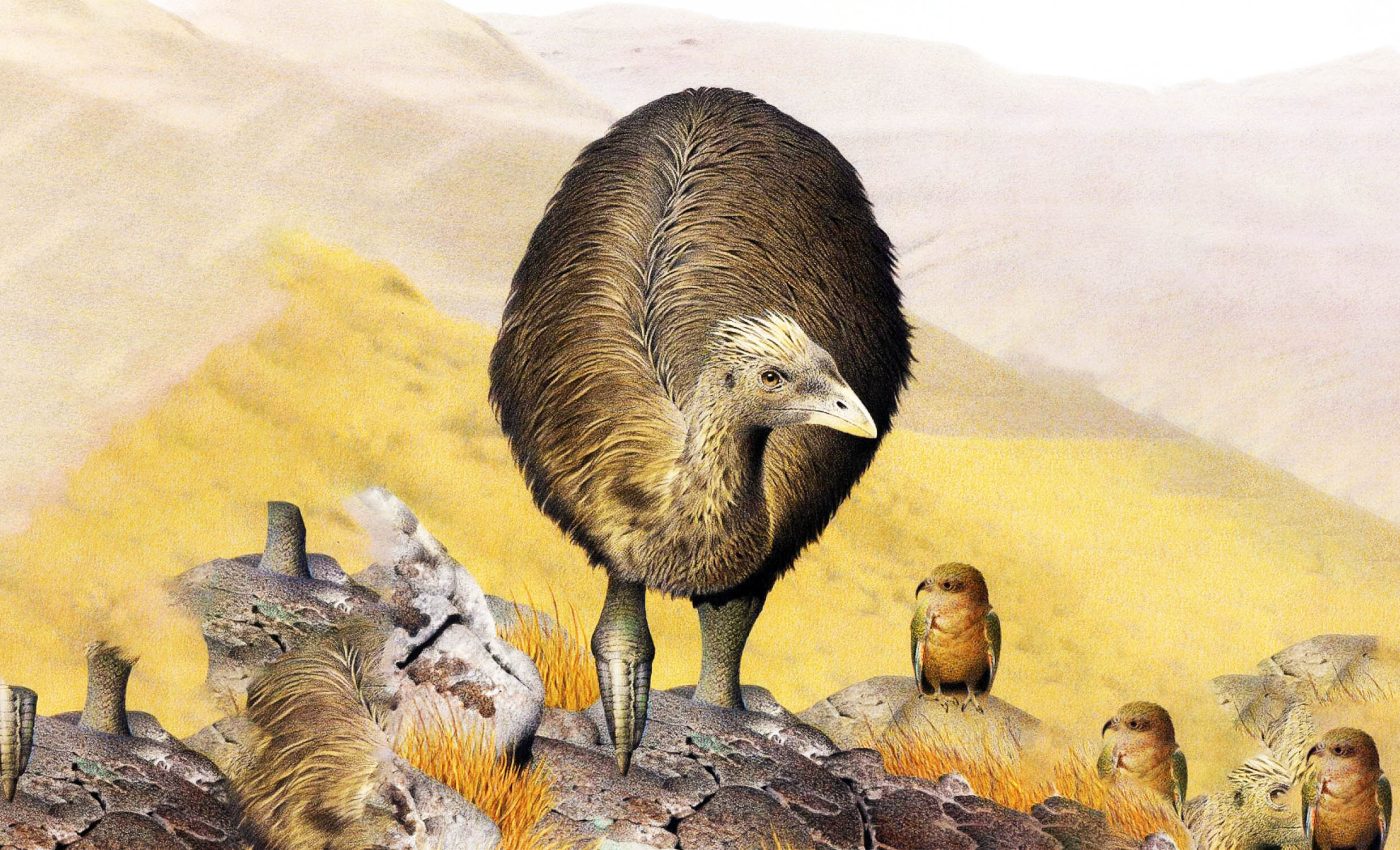

Giant moa bird, Pachyornis australis

In exploring the lives of the remarkable moa, Pachyornis australis, scientists have uncovered compelling insights into their habitats, which notably align with the current environments of several endangered flightless birds in New Zealand.

Species such as the vibrant takahē, the uniquely patterned weka, and the iconic great spotted kiwi now share these landscapes that were once dominated by the moa.

Dr. Sean Tomlinson, a prominent contributor to this extensive study, highlighted the importance of these findings.

“Populations of moa likely vanished first from the most desirable lowland habitats favored by Polynesian settlers due to their rich resources and biodiversity,” Tomlinson explained.

This connection not only sheds light on New Zealand’s ecological history but also prompts critical questions regarding contemporary conservation efforts for today’s vulnerable bird species.

How can we apply these historical insights to better protect our unique avian inhabitants?

This understanding emphasizes the urgency of addressing conservation challenges, bridging the past and present as we strive to safeguard the natural world.

Present moa bird conservation efforts

The story of New Zealand’s flightless birds, like Pachyornis australis, is one marked by significant challenges and obstacles.

It began with the arrival of the Polynesians, who not only hunted these unique avian species for sustenance but also dramatically altered their natural habitats through land clearing and the introduction of invasive vegetation.

This initial disruption sparked a series of ecological challenges that these birds continue to face.

The situation intensified with the arrival of European settlers in the 19th century, who introduced new predators — such as rats, cats, and stoats — that preyed on native birds and their eggs, further threatening their populations.

Preventing another extinction like Pachyornis australis

Additionally, extensive landscape modifications transformed forests into agricultural land and urban areas, resulting in the loss of crucial habitats for these flightless species.

Dr. Jamie Wood, a leading researcher in this field, sheds light on a vital insight regarding the survival of these birds.

“The key commonality among past and current refugia is not that they are optimal habitats for flightless birds, but that they continue to be the last and least impacted by humanity,” noted Wood.

This underscores the critical importance of safeguarding the remaining natural spaces that have escaped human interference; these areas may hold the key to the survival of New Zealand’s unique avian fauna.

Understanding this historical context is essential for informing conservation efforts aimed at ensuring a future for these remarkable creatures.

By exploring the complex interplay between human activity and ecological resilience, we can foster a greater appreciation for the natural world and the urgent need to protect it.

Scientists dedicated to moa bird research

The dedicated efforts of scientists like Associate Professor Fordham, Dr. Tomlinson, and Dr. Wood are crucial for uncovering the hidden patterns in nature that have long puzzled us.

Their innovative research not only deepens our understanding of historical ecological dynamics but also equips us with valuable tools for the conservation of endangered species facing urgent threats.

By meticulously analyzing various species, they reveal the interconnectedness of ecosystems and the significant impact of human activities on biodiversity.

As Dr. Fordham insightfully pointed out, “Our research shows that despite large differences in the ecology, demography, and timing of extinction of moa species, their distributions collapsed and converged on the same areas on New Zealand’s North and South Islands.”

This finding highlights the pressing need for informed conservation strategies that consider these intricate patterns and support the recovery of vulnerable species.

This ongoing research is not just academically intriguing; it is essential for fostering a sustainable future for wildlife and preserving the delicate balance of our planet’s ecosystems.

How can we apply these insights to ensure the survival of our natural world? Engaging with these complex issues invites us to think critically about our role in conservation and the well-being of our environment.

Moa birds, flightless birds, and extinction events

The story of New Zealand’s flightless birds serves as a poignant reminder of the complex conservation challenges that intertwine the past and present for these unique species.

Birds like the iconic kiwi have evolved in isolation, developing exceptional traits that also render them vulnerable to environmental shifts and introduced predators.

This study, which cleverly employs fossils and advanced computational models, opens new pathways for understanding and addressing threats to biodiversity. It allows researchers to reconstruct historical habitats and gain insights into how these birds have adapted over time.

But how can we ensure their survival? It requires a united effort from scientists, conservationists, and the public alike.

This underscores the critical importance of raising awareness and taking action not only to protect these remarkable birds but also to safeguard the ecosystems they inhabit.

By fostering community engagement and embracing scientific innovation, we can collectively strive for a more sustainable future for New Zealand’s wildlife. What steps will you take to contribute to this vital mission?

The full study was published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–