Earth's oceans are rapidly changing colors, and humans are directly to blame

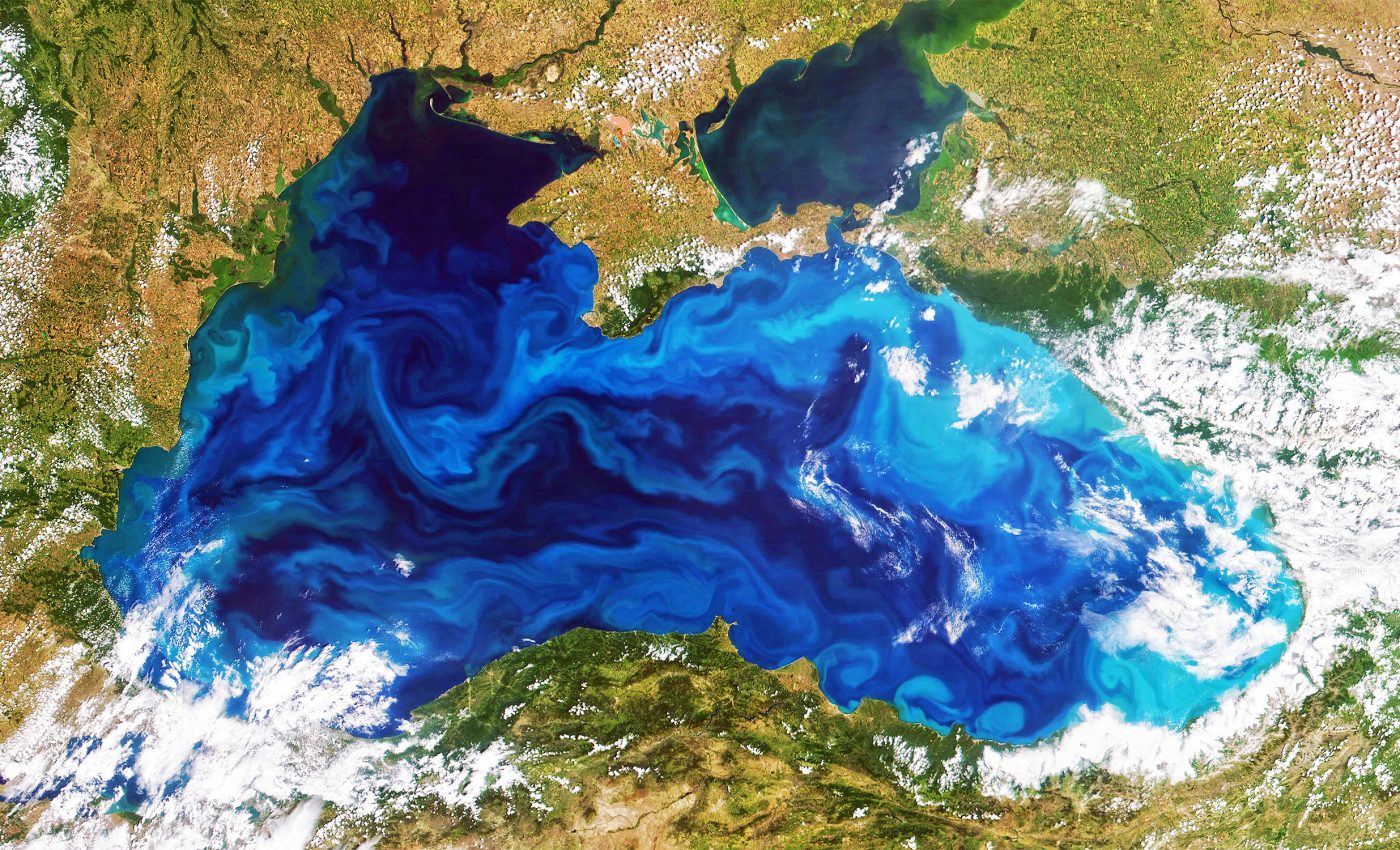

Over the past 20 years, scientists have observed a subtle but widespread shift in the color of our oceans. While these changes might not be noticeable during a day at the beach, you can easily see them from airplanes and satellites in space.

This is happening on a massive, global scale, signaling to anyone paying attention that significant transformations are taking place beneath the surface of our seas.

Sounding alarm bells

Stephanie Dutkiewicz, a senior research scientist at MIT, has been studying this phenomenon closely. She’s part of a team that’s raising concerns about what these color changes mean for the health of our planet.

“We hope people take this seriously,” says Dutkiewicz. “It’s not only models predicting these changes; we can now see them happening, and the ocean is changing.”

In a study published in Nature, researchers from the National Oceanography Center in the UK and other institutions revealed that more than half of the world’s oceans have experienced a shift in color.

They found that these changes can’t be chalked up to natural variations alone — they’re likely a result of human-driven climate change.

Greener ocean color near the equator

Tropical regions near the equator have become noticeably greener over time. This isn’t just a visual tweak; it’s a sign that the ecosystems within the surface ocean are changing.

The color of the ocean is influenced by what’s in its upper layers, especially tiny organisms like phytoplankton.

Phytoplankton are microscopic, plant-like creatures that contain chlorophyll, giving them their green tint. They’re a cornerstone of the marine food web and play a key role in capturing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Shifts in their populations can have ripple effects throughout marine ecosystems and impact the global carbon cycle.

Blame the humans, of course

Lead author B.B. Cael from the National Oceanography Center points out that this isn’t a random occurrence.

“This evidence shows how human activities are affecting life on Earth on a vast scale,” he says. “It’s another way humans are impacting the biosphere, affecting even the most extensive environments on the planet.”

Traditionally, scientists have monitored chlorophyll levels to keep tabs on phytoplankton populations. But tracking changes using chlorophyll alone can take decades because of natural year-to-year fluctuations.

Back in 2019, Dutkiewicz and her colleagues suggested that looking at the full spectrum of ocean colors could reveal climate change-driven trends more quickly. They estimated that such changes could become apparent within 20 years.

Satellites spot the difference

The team analyzed data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite.

Since 2002, this instrument has been observing ocean color across seven visible wavelengths. Their analysis showed a clear trend over two decades, lining up with what their models had predicted.

Cael explains that these trends match up with the effects of human-induced climate change, not just random shifts in the Earth’s system.

This means the changes in ocean color are a direct response to how we’re altering the planet’s climate.

Why does ocean color matter?

So, what’s the big deal about the ocean turning a bit greener? It suggests that the types of phytoplankton communities are changing.

Different phytoplankton have varying abilities to capture carbon and support marine life. Changes in these communities can affect the entire food web, from tiny marine organisms all the way up to fish and whales.

Dutkiewicz emphasizes that these shifts will impact all creatures that rely on plankton for food.

“Different types of plankton influence how much carbon the ocean can absorb,” she notes, highlighting the broader implications for climate regulation.

Visible sign of invisible changes

This research shines a light on the far-reaching effects of climate change on marine ecosystems. Monitoring ocean color offers a tangible way to detect and understand these shifts.

The findings are a stark reminder of the significant impact human activities have on Earth’s complex systems.

“The evidence is clear: human activities are altering the very color of our oceans,” says Cael. This isn’t just about aesthetics; it’s about the intricate balance of marine life that keeps our planet healthy.

What can we do to help?

This shift in the ocean’s hue is more than just a scientific curiosity — it’s a call to action.

Scientists are continuing to study these trends to grasp the full impact on marine ecosystems and the global climate.

By keeping a closer eye on the full spectrum of ocean colors, researchers hope to gain a quicker understanding of how climate change is affecting the oceans.

This could lead to faster responses and more effective strategies to lessen the impacts.

As we face the realities of climate change, understanding what’s happening in our oceans is crucial. Changes in the oceans can affect weather patterns, sea levels, and biodiversity on a global scale.

Addressing these challenges isn’t something scientists can do alone. It requires all of us to pitch in — from reducing our carbon footprints to supporting policies that protect marine environments.

Every action, no matter how small, contributes to the bigger picture.

Ocean color, climate change, and human health

To sum it all up, scientists have noticed that over the past 20 years, more than half of the world’s oceans have subtly changed color.

Stephanie Dutkiewicz points out that this shift matches what climate change models have been predicting.

The color change is linked to alterations in phytoplankton communities — tiny, plant-like organisms with chlorophyll that give the ocean its green tint.

These little guys are essential for marine life and play a big role in capturing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

By analyzing satellite data, researchers found that these changes aren’t just natural fluctuations; they’re consistent with human-driven climate change.

The shift in ocean color suggests significant changes in marine ecosystems, which could impact the entire food web — from microscopic organisms to large marine animals.

This finding highlights how human activities are affecting the planet in profound ways, even down to changing the very color of our oceans. It’s a clear sign that we need to take climate change seriously and start making changes now.

The full study was published in the journal Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–