How did Earth finally produced enough oxygen to escape the ‘boring billion’?

How did Earth finally produced enough oxygen to escape the ‘boring billion’?. For roughly half of our planet’s 4.6 billion year lifetime, its atmosphere was made up of only carbon dioxide and nitrogen – not exactly a friendly place to exist if you happen to be an oxygen-consuming life form.

Luckily for us, oxygen started to come into the picture when cyanobacteria – also known as blue-green algae – began producing the first oxygen through the enzyme nitrogenase, which can be traced back to the universal common ancestor of all cells over four billion years ago.

This oxygen-producing process began the Great Oxidation Event, and while that sounds like an ideal band name, the years that followed were less exciting than its title might lead you to believe.

“Instead of rising steadily, atmospheric oxygen levels stabilized at 2% by volume for about two billion years before increasing to today’s level of 21%,” explains Professor John Allen of University College London’s Genetics, Evolution & Environment department. “The reasons for this have been long debated by scientists and we think we’ve finally found a simple yet robust answer.”

Allen and researchers from UCL, Queen Mary University of London and Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf have published a study in Trends in Plant Sciences proposing for the first time that atmospheric oxygen produced using the enzyme nitrogenase actually prevented the enzyme from working. The researchers posit that a negative feedback loop halted further oxygen from being produced, and began an exceedingly long period of stagnation in the Earth’s history – like two billion years long.

About 2.4 billion years ago, the Proterozoic Eon experienced very little change in the evolution of life, ocean, atmosphere composition, and climate, which is why some refer to it as the “boring billion.”

“There are many ideas about why atmospheric oxygen levels stabilized at 2% for such an incredibly long period of time, including oxygen reacting with metal ions, but remarkably, the key role of nitrogenase has been completely overlooked,” says study co-author Professor William Martin of Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf. “Our theory is the only one that accounts for the global impact on the production of oxygen over such a sustained period of time and explains why it was able to rise to the levels we see today, fueling the evolution of life on Earth.”How did Earth finally produced enough oxygen to escape the ‘boring billion’?

The researchers suggest that this negative feedback loop was only broken when plants finally moved onto land roughly 600 million years ago. With the emergence of plants onto land, oxygen producing cells in leaves were physically separated from nitrogenase containing cells in soil, allowing for oxygen to accumulate without inhibiting nitrogenase.

Their theory is bolstered by evidence within the fossil record showing cyanobacteria began to protect nitrogenase in dedicated cells called heterocysts a little over 400 million years ago – at the time when oxygen levels were already increasing from photosynthesis in land plants.

“Nitrogenase is essential for life and the process of photosynthesis as it fixes nitrogen in the air into ammonia, which is used to make proteins and nucleic acids,” explains co-author Mrs Brenda Thake of Queen Mary University of London. “We know from studying cyanobacteria in laboratory conditions that nitrogenase ceases to work at higher than 10% current atmospheric levels, which is 2% by volume, as the enzyme is rapidly destroyed by oxygen. Despite this being known by biologists, it hasn’t been suggested as a driver behind one of Earth’s great mysteries, until now.”

—

By Connor Ertz, Earth.com Staff Writer

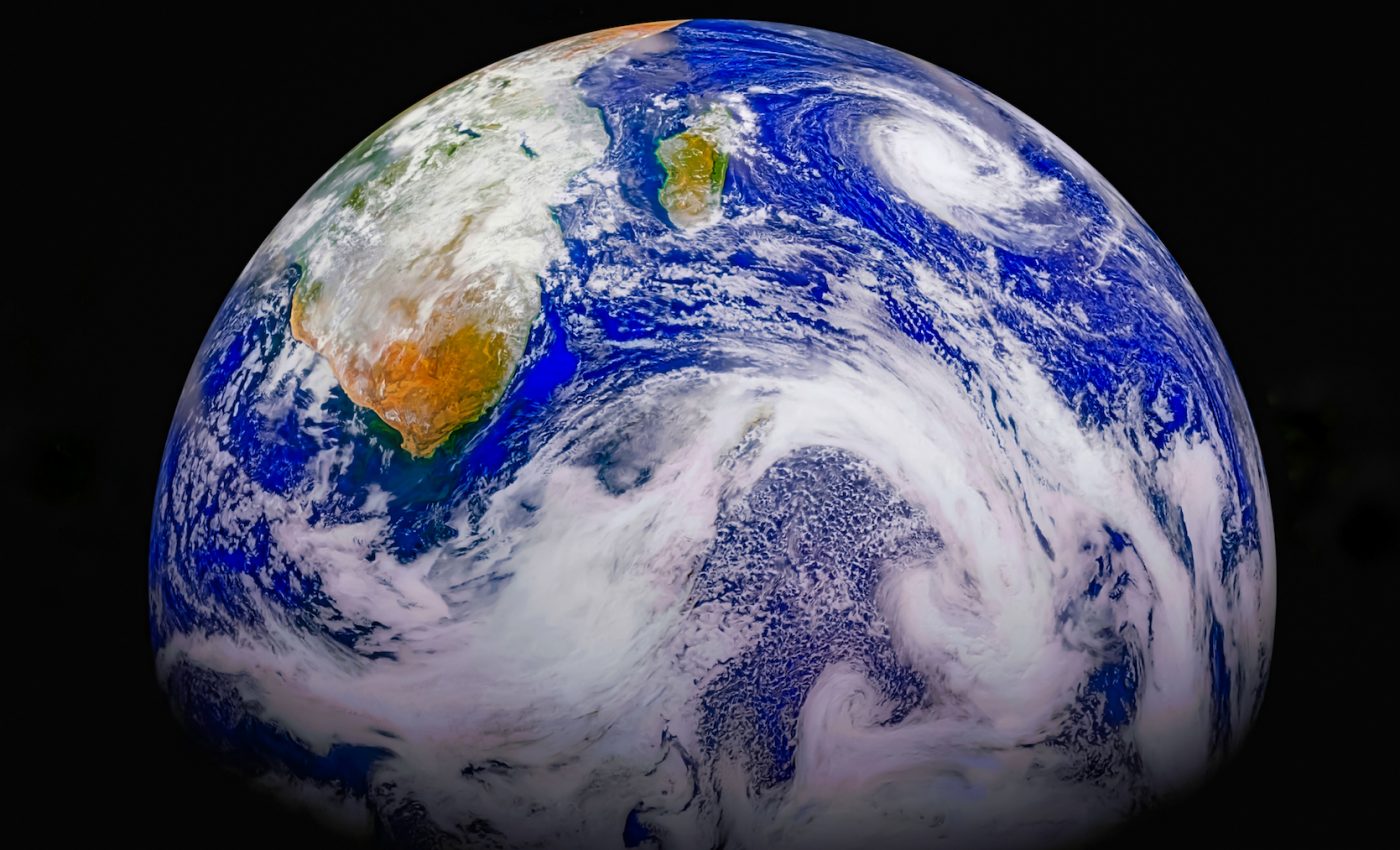

Image Credit: Shutterstock/Digital Images Studio