Discovery: Early humans in America coexisted with giant sloths and mastodons

Giant sloths once roamed across much of the Americas. Modern humans often picture sloths as slow animals clinging to tree branches, but their prehistoric relatives weighed more than 8,000 pounds and sometimes reacted aggressively if they felt threatened.

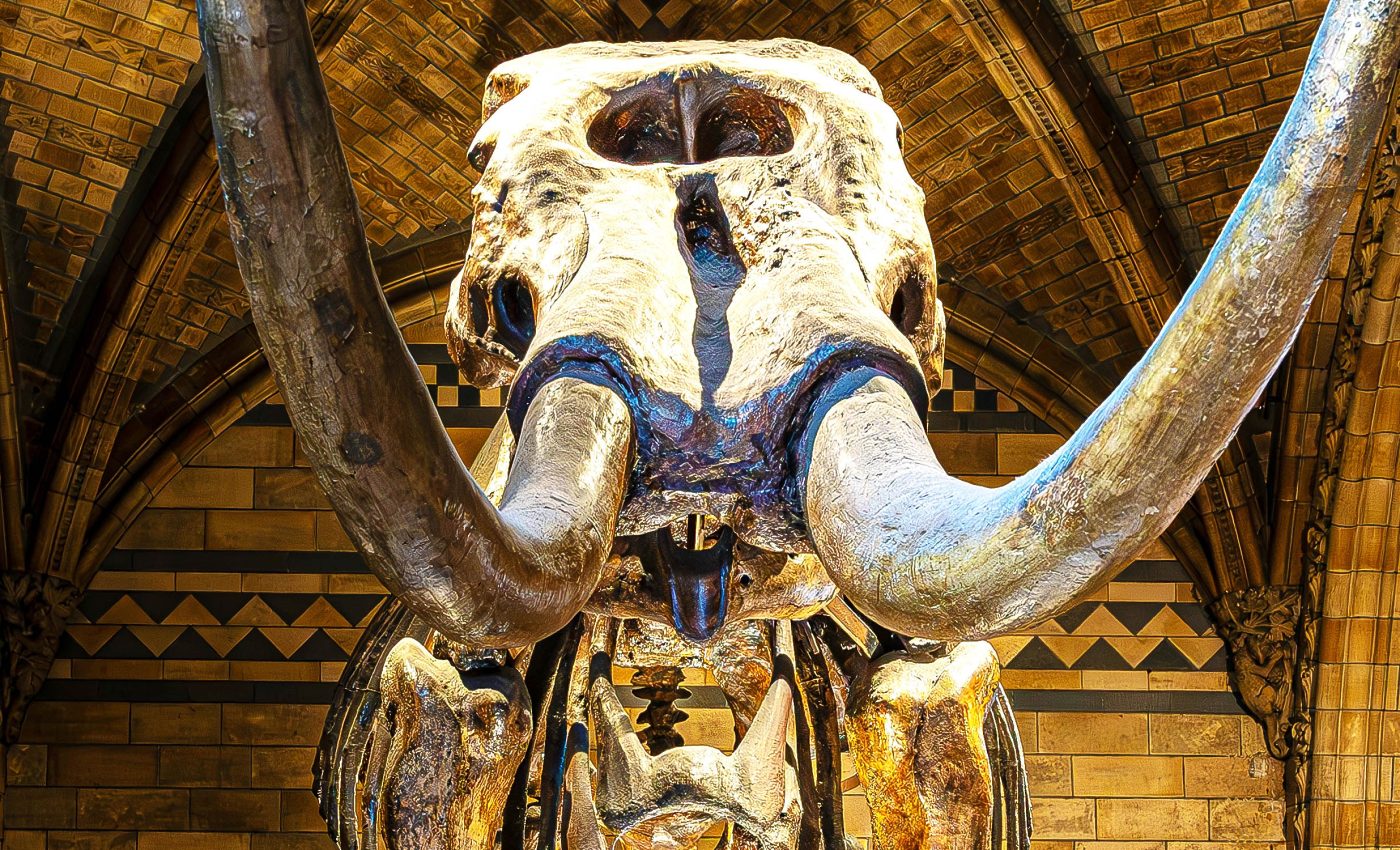

At the same time, ancient mastodons grazed across plains and wetlands, forming part of a landscape filled with towering mammals that would turn heads in any museum exhibit.

Humans coexistence with sloths

For many years, scientists believed that humans set foot in the Americas around 13,000 years ago and rapidly hunted massive creatures like giant ground sloths and saber-toothed cats into extinction.

This theory, called Pleistocene overkill, painted a picture of speedy destruction.

However, researchers from different archaeological sites have recently suggested that people may have arrived much earlier and may have coexisted with these animals for thousands of years.

Ancient footprints in New Mexico

Daniel Odess, an archaeologist at White Sands National Park in New Mexico, is among those revisiting the old timeline.

His team has analyzed evidence from footprints and geological layers that could date human presence in North America to more than 20,000 years ago.

These footprints appear alongside the tracks of mammoths, giant ground sloths, and other ancient creatures. Some experts question why footprints remain but few other artifacts have turned up.

Yet the discovery suggests that humans spent many generations adapting to a dramatic environment, rather than simply arriving and wiping out large species in a short period.

Sloth fossils reveal human presence

Sloth fossils from Santa Elina, an archaeological site in central Brazil, have stirred fresh discussions about the timeline.

Researchers there have unearthed the fossilized remains of giant ground sloths that show signs of human handiwork. These prehistoric bones feature small holes and polished edges that differ from untouched remains.

“We believe it was intentionally altered and used by ancient people as jewelry or adornment,” said researcher Mírian Pacheco.

Jewelry from ‘fresh bones’

One puzzle centered on whether this jewelry came from old fossils or from bones that were still fresh and relatively new.

Laboratory analysis suggests these sloth bones were shaped and drilled not long after the animals died, hinting at a human presence in South America more than 25,000 years ago.

Some bones also show dark coloration. Early findings point to possible burning at campfires, though researchers continue to explore alternative explanations, such as chemical changes in the soil.

Debates and different interpretations

The site at Santa Elina is only one example among several that point to the idea of an older human presence in the Western Hemisphere.

In Chile, Monte Verde gained worldwide attention when stone tools and preserved vegetation were dated to about 14,500 years ago.

Uruguay’s Arroyo del Vizcaíno site has yielded animal bones with possible cut marks that may date back 30,000 years.

Older dates consistently generate skepticism from some experts. People often ask whether there might be errors in dating techniques or whether non-human processes could explain the markings.

Scientists like Odess remain open to these critiques and emphasize that it takes time and multiple confirmations for a hypothesis to gain acceptance.

Living among Ice Age giants

As research grows, a new picture emerges of humans who spent millennia wandering with mastodons, giant sloths, and other imposing animals.

Paleontologist Thais Pansani and her colleagues note that early campsites may have included hearths that left burn marks on large bones.

These details give us a sense of daily life in a time when massive creatures ambled across landscapes quite different from modern farms and highways.

Although the popular view once held that people showed up and immediately caused extinctions, the latest findings propose a longer period of coexistence.

Climate shifts disrupted habitats

If humans arrived earlier, why didn’t they drive giant mammals to immediate extinction? Scientists have started to suggest a wider web of factors, including changes in climate.

When the Ice Age ended, shifting habitats may have disrupted food sources and water supplies for large herbivores and the predators that hunted them.

People may have contributed to the extinctions, but it appears that climate shifts played a role, too. The timing of events is still under scrutiny, and not every site’s data line up perfectly, but the story is growing more complex.

Challenges in dating and evidence

Dating techniques rely on methods such as radiocarbon analysis of charcoal or bones, geological correlations, and DNA tests that reveal genetic timelines.

Each tool has strengths and weaknesses, so researchers weigh multiple approaches.

Unusual finds, like footprints without additional artifacts, make some archaeologists cautious.

Yet repeated patterns of evidence are shifting attitudes toward the possibility that humans reached the Americas well before the traditional 13,000-year mark.

Humans, sloths, and mastodons

No single discovery will settle the debates. Instead, each new fossil sample and archaeological layer adds a piece to a changing puzzle.

Researchers continue to test bones, re-check radiocarbon dates, and compare footprints to the surrounding sediments.

Whether the first arrivals journeyed by land, sea, or both, many specialists agree that older dates are worth taking seriously.

Giant sloths, mastodons, saber-toothed cats, and even ancient horses likely shared vast grasslands and wetlands with humans, at least for a while.

Their interactions remain difficult to trace, but our understanding of the distant past grows richer as new investigations move forward.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–