Drugs targeting gut cells for depression and anxiety work better than those targeting brain cells

Many people have felt a twist in their stomach when emotions run high. It can happen during tense or stressful moments, and when sadness or depression makes a person lose interest in eating.

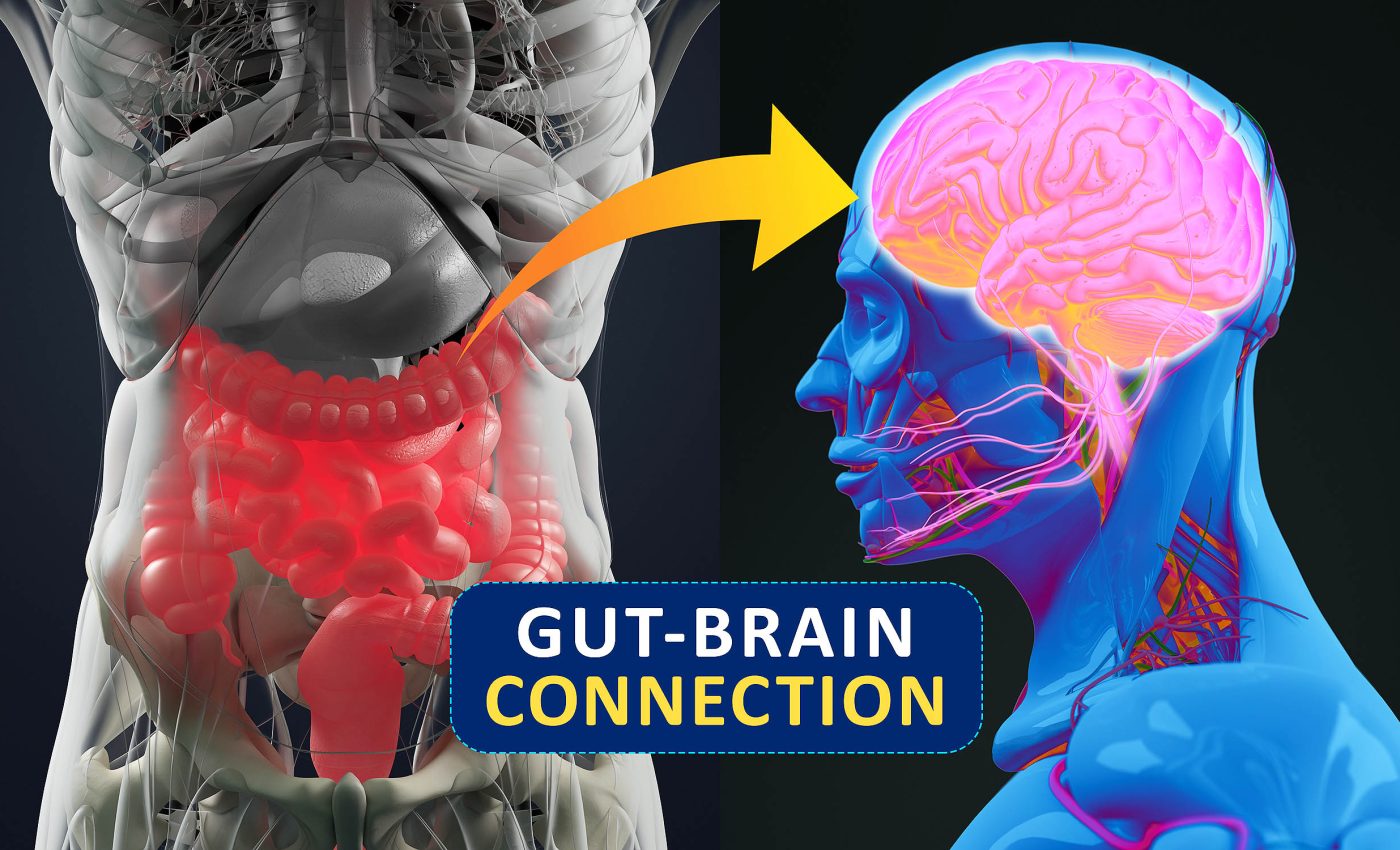

This everyday experience points to connections inside the body, between the mind and the gut, that aren’t always obvious and are often overlooked.

For years, treatments that affect the brain have been used to lift spirits. Yet new research suggests a different path — focusing on that “gut feeling.”

Gut treatment, not brain treatment

A recent animal study explored the idea of focusing treatments for depression and anxiety to cells inside the gut rather than brain cells.

This shift may help people feel better without the unwelcome side effects that can come with drugs affecting the entire body.

These findings were led by Mark Ansorge, associate professor of clinical neurobiology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, and Kara Margolis, Director of the NYU Pain Research Center and an associate professor of molecular pathobiology in the NYU College of Dentistry.

They looked closely at how treatments often used for depression and anxiety might work differently when kept mostly in the intestines.

“Antidepressants like Prozac and Zoloft that raise serotonin levels are important first-line treatments and help many patients but can sometimes cause side effects that patients can’t tolerate,” Ansorge explains.

“Our study suggests that restricting the drugs to interact only with intestinal cells could avoid these issues.”

SSRI treatment in the gut

The standard approach to dealing with persistent sadness or worry has long involved drugs called SSRIs. They affect serotonin, a chemical known to help messages move around in the brain.

The problem is that these treatments spread everywhere, not just in the head. Changing that could make a big difference.

“But not treating a pregnant person’s depression also comes with risks to their children,” Ansorge says. “An SSRI that selectively raises serotonin in the intestine could be a better alternative.”

For decades, no one gave much thought to serotonin outside the brain. Yet there is a lot of it sitting right in the intestines.

“In fact, 90% of our bodies’ serotonin is in the gut”, says Margolis, who is also an associate professor of pediatrics and cell biology at NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

This inside story may explain why some people experience stomach upset along with mood issues.

If balancing serotonin only in the intestines can influence a person’s feelings, then future treatments might avoid the usual problems linked to current medications.

How the study was done

To explore this, researchers worked with mice. They used genetic engineering, surgery, and drugs to increase serotonin signaling in the gut but not in other parts of the body.

The question was simple: Would these changes help the mice behave in ways that suggest relief from anxiety or low mood?

“These results suggest that SSRIs produce therapeutic effects by working directly in the gut,” Ansorge says.

What did they learn?

The results were surprising. The mice acted calmer and less down, yet they did not show the usual side effects often tied to SSRIs that affect the entire body.

“Based on what we know about interactions between the brain and gut, we expected to see some effect. But to see enhanced serotonin signaling in the gut epithelium produce such robust antidepressant and anxiety-relieving effects without noticeable side effects was surprising even to us,” Ansorge enthused.

“There may be an advantage to targeting antidepressants selectively to the gut epithelium,” adds Margolis. “Systemic treatment may not be necessary for eliciting the drugs’ benefits.”

Gut-brain connection

This approach did not just help the mood of the mice. It also revealed something new about how the body’s internal wiring works.

Signals going from the gut up to the head seem to matter. The vagus nerve, known for carrying messages between these regions, was key.

Instead of the brain telling the belly what to do, the gut’s signals played a role in shaping mood.

Understanding the vagus nerve — the basics

The vagus nerve is like your body’s superhighway for communication between your brain and various organs. It’s one of the longest nerves in your body, stretching from your brainstem all the way down to your abdomen.

Think of it as a major player in your autonomic nervous system, which controls things you don’t have to think about, like your heart rate, digestion, and breathing.

When you take a deep breath, feel your heart beat, or even swallow your food, that’s the vagus nerve doing its job.

It helps keep everything running smoothly by sending signals back and forth, ensuring your body responds appropriately to different situations.

But the vagus nerve does more than just manage basic functions — it also plays a role in your mood and overall sense of well-being.

Stimulating the vagus nerve, whether through activities like deep breathing, meditation, or even certain medical treatments, can help reduce stress and promote relaxation.

This nerve is involved in the “rest and digest” response, helping to calm your body after you’ve been stressed or active.

Pregnancy concerns

Problems can arise when certain drugs cross the placenta. Past work has linked these exposures with issues in children.

The researchers studied more than 400 mothers and babies and found that children exposed to these antidepressants were 3 times more likely to develop constipation in their first year of life.

“Maternal depression and anxiety can have many unwanted effects on fetal and child development and must thus be treated and monitored adequately to the benefit of both mother and child,” says Ansorge.

Drugs, guts, brains, and the future

The team is now working to create an SSRI that stays in the gut. If they succeed, it might change how doctors help people dealing with serious sadness and worry.

This approach could matter especially for those expecting a child, since it would mean addressing mood concerns without running the risks that come with the usual treatments.

Keeping these treatments focused on the intestines might give people a better shot at feeling like themselves again.

For many, this line of thinking stands as a reminder that what happens inside the body often comes down to more than what goes on in the head.

It suggests a future where relief could come without the troubles that keep so many from getting the help they need.

The full study was published in the journal Gastroenterology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–