Collapse of Earth's global water circulation system is already happening

You probably know at least a little bit about ocean circulation around the world, also known as currents. In fact, you may have felt smaller currents yourself on a day at the beach.

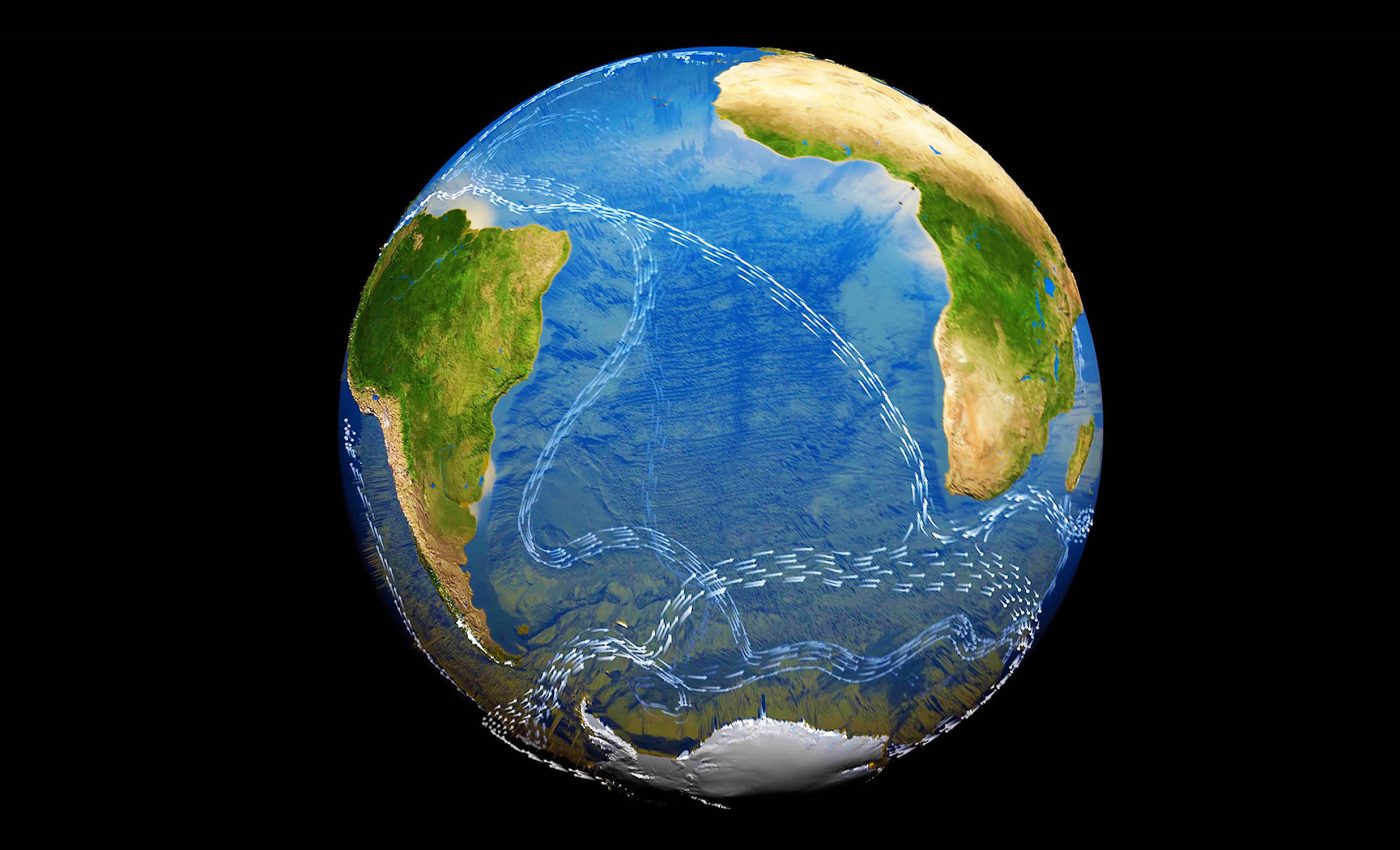

But have you heard bout the “great global ocean conveyor belt,” which is a vast network of currents that constantly moves water around the entire planet?

This massive system helps distribute heat around the world, influencing everything from temperatures to rainfall. Unfortunately, it’s slowing down and on the verge of total collapse.

Scientists have been studying this phenomenon, and according to recent research published in Nature Geoscience, it’s a bigger deal than we thought.

Ocean circulation and the AMOC?

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC, is like a massive ocean conveyor belt that moves warm and cold water around the Atlantic Ocean.

It starts in the Gulf of Mexico, where warm, salty water flows northward along the eastern coast of the United States and across the Atlantic towards Europe.

As this warm water reaches the North Atlantic, it cools down, becomes denser, and sinks deep into the ocean.

This sinking process pulls more warm water north to replace it, creating a continuous loop that helps regulate the climate by distributing heat across the planet.

AMOC’s impact on humans

Thanks to the AMOC, regions like Western Europe enjoy milder winters than they would otherwise.

Humans rely on the AMOC in several important ways. By regulating global temperatures, it helps maintain stable weather patterns, which are crucial for agriculture, ecosystems, and our daily lives.

Researchers point out that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is now weaker than at any other time in the past 1,000 years.

The research team from several leading universities explains that global warming is behind this slowdown.

Their new modeling suggests that meltwater from the Greenland ice sheet and Canadian glaciers could be the missing piece of the puzzle.

Why should we care ocean water circulation?

“Our results show the Atlantic overturning circulation is likely to become a third weaker than it was 70 years ago at 2°C of global warming,” says the research team.

“This would bring big changes to the climate and ecosystems, including faster warming in the southern hemisphere, harsher winters in Europe, and weakening of the northern hemisphere’s tropical monsoons.”

Think about that for a second. A weaker ocean current could mean colder winters in Europe and shifts in rainfall patterns that affect millions of people. It’s not just about the ocean; it’s about our daily lives.

Meltwater and ocean circulation

The Earth has already warmed 1.5ºC since the industrial revolution, and the Arctic has been heating up nearly four times faster than the rest of the planet.

All that heat is melting Arctic sea ice, glaciers, and the Greenland ice sheet.

“Since 2002, Greenland lost 5,900 billion tons (gigatons) of ice,” notes the research team. “To put that into perspective, imagine if the entire state of Texas was covered in ice 26 feet thick.”

All this fresh meltwater flowing into the subarctic ocean is lighter than salty seawater, so it doesn’t sink as much.

That messes with the southward flow of deep, cold waters from the Atlantic and weakens the Gulf Stream — the same current that gives Britain its mild winters.

Ripple effects around the globe

So, what’s the big deal with the Gulf Stream slowing down? Well, for starters, Europe could face harsher winters.

Places like Britain might start feeling more like their chilly counterparts at the same latitude, such as parts of Canada.

“Our new research shows meltwater from the Greenland ice sheet and Arctic glaciers in Canada is the missing piece in the climate puzzle,” the researchers explain.

When they included this meltwater in their simulations, the slowing of the oceanic circulation made sense.

The study confirms that the Atlantic overturning circulation has been slowing down since the mid-20th century. It also gives us a sneak peek into what’s coming next.

Northern and Southern ocean circulation

“Our new research also shows the North and South Atlantic oceans are more connected than previously thought,” the team states.

Changes in one part of the ocean can quickly affect distant regions. When the oceanic circulation is strong, it transfers a lot of heat to the North Atlantic.

But when it weakens, the surface of the ocean south of Greenland doesn’t warm up as much, leading to what’s called a “warming hole.” Meanwhile, the South Atlantic ends up storing more heat and salt.

Time is not on our side

“Our simulations show changes in the far North Atlantic are felt in the South Atlantic Ocean in less than two decades,” the researchers reveal. This means the effects of the slowdown are spreading faster than we thought.

Climate projections have suggested the Atlantic overturning circulation will weaken by about 30% by 2060. But hold on — that’s without considering all that extra meltwater.

“The Greenland ice sheet will continue melting over the coming century, possibly raising global sea level by about 4 inches,” the study notes.

“If this additional meltwater is included in climate projections, the overturning circulation will weaken faster. It could be 30% weaker by 2040. That’s 20 years earlier than initially projected.”

What can we do?

Such a rapid decrease in the overturning circulation will shake things up.

Europe might see colder winters, the northern tropics could get drier, and places like the southern United States might experience warmer, wetter summers.

“Our climate has changed dramatically over the past 20 years,” the researchers warn. “More rapid melting of the ice sheets will accelerate further disruption of the climate system.”

So, what does this all mean for us? It means we have even less time to get our act together. Reducing emissions isn’t just a good idea — it’s crucial.

Our planet’s systems are interconnected in ways we’re only beginning to understand. If we want to keep things from getting worse, we need to act now. Every little bit counts, and the clock is ticking.

The full study was published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–