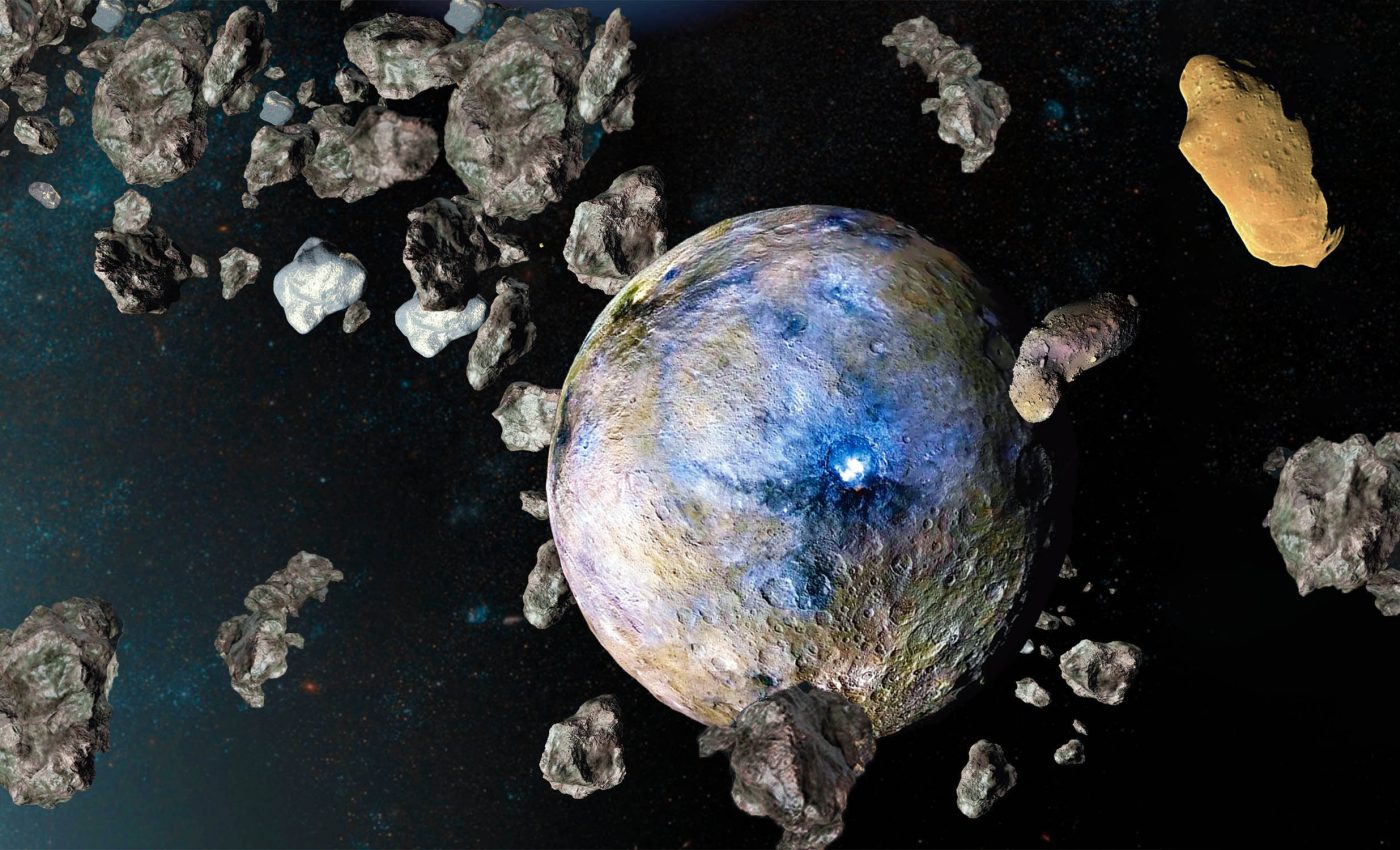

Largest asteroid in our solar system used to be an ocean planet

For over two centuries, Ceres has captivated astronomers as the largest asteroid in our solar system. Discovered in 1801 by Giuseppe Piazzi, this dwarf planet nestled in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter has long been a subject of intrigue and study.

Recent research, however, is shedding new light on Ceres, challenging our previous understanding of its composition and history.

The findings suggest that Ceres may harbor a substantial amount of water ice beneath its surface, painting a picture of an ancient ocean world.

Rewriting the story of asteroid Ceres

Traditionally, scientists believed that Ceres was relatively dry, estimating its ice content to be less than 30%. This assumption stemmed from the observation of numerous impact craters on its surface, which indicated a lack of significant ice.

Dr. Mike Sori, an assistant professor in Purdue’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, and Ian Pamerleau, a PhD student at Purdue, alongside Jennifer Scully from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL), are the brains behind these new insights into Ceres’ icy nature.

“People used to think that if Ceres was very icy, the craters would deform quickly over time, like glaciers flowing on Earth, or like gooey flowing honey,” explained Dr. Sori.

“However, we’ve shown through our simulations that ice can be much stronger in conditions on Ceres than previously predicted if you mix in just a little bit of solid rock.”

This revelation flips the script on decades-old theories. The research team utilized advanced computer simulations to model how Ceres’ craters have evolved over billions of years.

Their work suggests that the surface of Ceres is composed of a “dirty ice crust,” which is predominantly ice mixed with rocky material.

This mixture allows the ice to remain stable over extensive periods, preserving the crater structures that once led scientists to believe Ceres was mostly dry.

Surprising data from NASA’s Dawn mission

NASA’s Dawn mission, launched on September 27, 2007, played a crucial role in this discovery. As the first and only spacecraft to orbit two extraterrestrial bodies — Vesta and Ceres — Dawn provided invaluable data from 2015 to 2018.

“We used multiple observations made with Dawn data as motivation for finding an ice-rich crust that resisted crater relaxation on Ceres,” Pamerleau noted.

The spacecraft’s spectrographic data indicated the presence of ice beneath Ceres’ surface, and gravity measurements supported the idea of an impure ice composition.

The team’s simulations accounted for a new way that ice can flow when even a small amount of rocky material is present.

This finding reconciles the presence of numerous craters with the high ice content, suggesting that Ceres could indeed be an icy world without the surface ice rapidly flowing away.

“We tested different crustal structures in these simulations and found that a gradational crust with a high ice content near the surface that grades down to lower ice with depth was the best way to limit relaxation of Cerean craters,” Pamerleau added.

No ordinary asteroid

Ceres stands out not just for its size — about 940 kilometers (584 miles) in diameter making it the most massive object in the asteroid belt — but also for its complex geology.

“Ceres really looks more like a planet,” Dr. Sori remarked. Its nearly spherical shape, along with features like craters, volcanoes, and landslides, make it a fascinating subject for planetary scientists.

The idea that Ceres could have been an ocean world similar to Jupiter’s moon Europa opens up exciting possibilities.

“To me, the exciting part of all this, if we’re right, is that we have a frozen ocean world pretty close to Earth,” said Dr. Sori.

This makes Ceres an attractive target for future missions aiming to explore potential subsurface oceans and the conditions that might support life.

Window into the solar system’s past

Understanding Ceres’ composition and history offers valuable clues about the early solar system.

As the largest asteroid, Ceres holds a significant portion of the asteroid belt’s mass, making it a key player in theories about planetary formation and the distribution of water in our solar neighborhood.

“Ceres may be a valuable point of comparison for the ocean-hosting icy moons of the outer solar system,” Dr. Sori explained.

Moreover, the discovery of a dirty ice crust suggests that Ceres could have resources like water ice, which might be crucial for future space exploration endeavors.

This ice could potentially be used for life support or as a component for fuel, making Ceres not just an object of scientific interest but also a potential hub for human activity in space.

What comes next for asteroid Ceres?

With Ceres now identified as a likely icy world, the next steps for scientists involve more detailed exploration.

Future missions could aim to drill below the surface to directly sample the ice and rocky mixture, providing definitive evidence of Ceres’ oceanic past.

Additionally, studying Ceres helps scientists draw parallels with other icy bodies, enhancing our understanding of the conditions that lead to the formation of oceans and possibly life.

Dr. Sori and his team emphasize that Ceres is the most accessible icy world we know of, making it an ideal candidate for continued exploration.

“Some of the bright features we see at Ceres’ surface are the remnants of Ceres’ muddy ocean, now mostly or entirely frozen, erupted onto the surface,” Pamerleau said.

This presents a unique opportunity to collect samples from an ancient ocean without the extreme challenges posed by more distant icy moons.

Solar system mysteries

To sum it all up, the newfound understanding of Ceres as an icy giant reshapes our perspective on the asteroid belt and the broader dynamics of our solar system.

By confirming that Ceres has a significant ice component, researchers have answered longstanding questions while spawning new ones about the potential for life and the history of water in our celestial neighborhood.

The full study was published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–