Black hole formation can be "gentle" without producing a supernova

Astronomers have stumbled upon something truly remarkable: a black hole that’s not just part of a binary system, but part of a trio.

This unusual system includes a black hole and two stars — one orbiting very close and the other much farther away.

It’s the first time scientists have observed such a configuration, and it’s turning some long-held theories on their heads.

Kevin Burdge, a Pappalardo Fellow in the MIT Department of Physics, led the team that made this surprising discovery. His work is opening up new questions about how black holes form and evolve.

The research suggests that black holes might not always form the way we thought they did. Instead of being born from violent explosions, some might emerge more quietly, without the dramatic fireworks of a supernova.

Black hole in a triple system

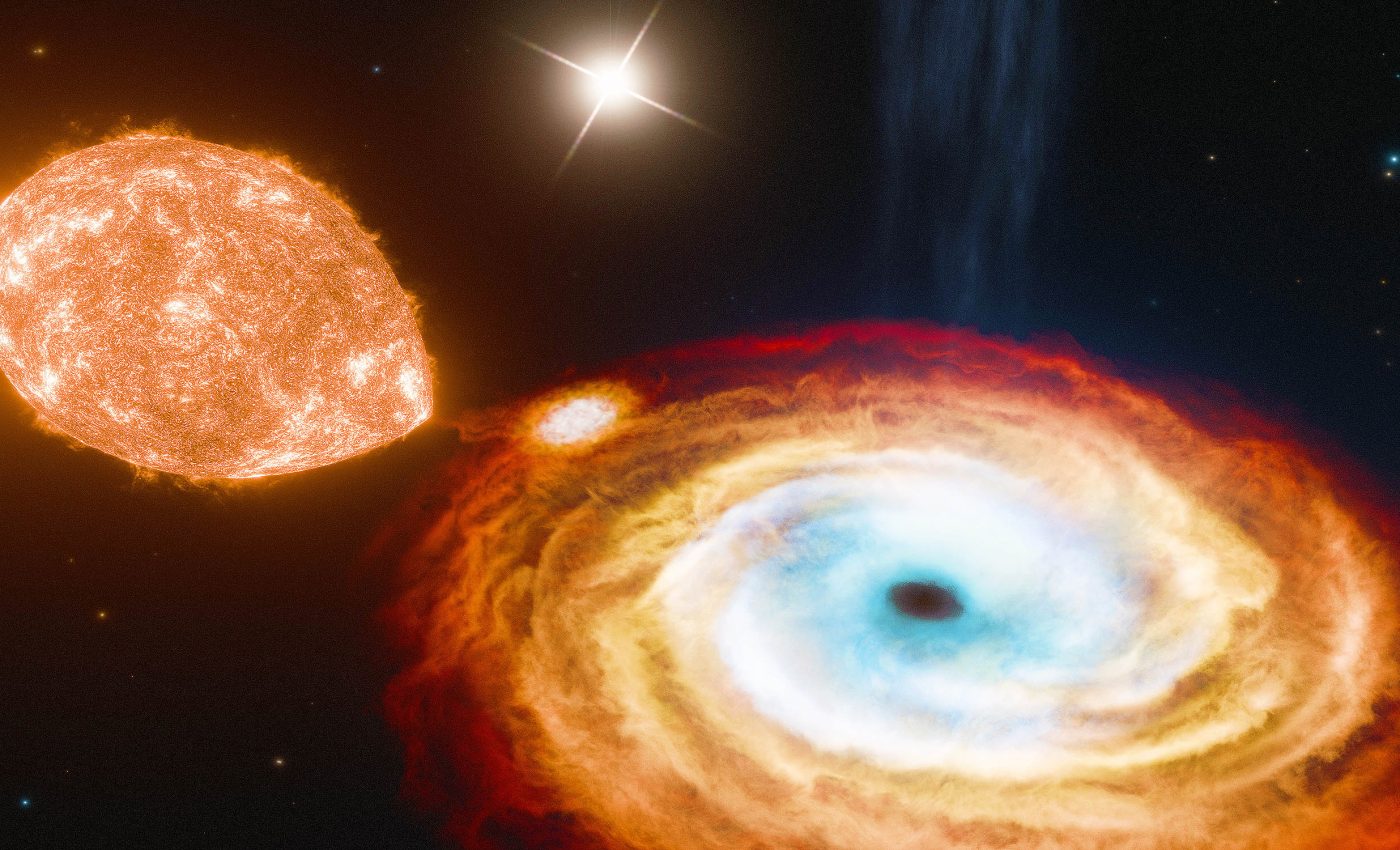

In most cases, black holes are found in binary systems. That means they have a companion — usually a star or another black hole — that they orbit closely due to their immense gravity. But this new system is different.

There’s a black hole at the center, consuming a small star that orbits it every 6.5 days. That’s pretty typical. What’s not typical is the second star, which is also orbiting the black hole but at a much greater distance. This outer star takes about 70,000 years to complete one orbit.

To put that into perspective, the outer star is about 3,500 astronomical units (AU) away from the black hole. One AU is the distance between the Earth and the Sun, so this star is 3,500 times that distance away. That’s also about 100 times the distance between Pluto and the Sun.

Challenging the supernova theory

The big question is, how can a black hole keep hold of a star that’s so far away?

According to our current understanding, black holes form from the violent explosion of a dying star — a supernova.

Such an explosion would release so much energy that any loosely bound objects nearby would be kicked away. So, the outer star shouldn’t still be hanging around.

“We think most black holes form from violent explosions of stars, but this discovery helps call that into question,” says Burdge.

“This system is super exciting for black hole evolution, and it also raises questions of whether there are more triples out there.”

Direct collapse theory

The team believes that the black hole in this system may have formed through a more peaceful process known as direct collapse.

In this scenario, a massive star simply caves in on itself, forming a black hole without the dramatic explosion. This gentle collapse wouldn’t disturb any distant companions, allowing the outer star to remain in orbit.

Direct collapse is a concept that’s been discussed in theoretical astrophysics, but observational evidence has been hard to come by.

If this black hole indeed formed through direct collapse, it could be the first concrete example supporting this theory.

How did astronomers find it?

Interestingly, the discovery happened almost by chance. Burdge and his colleagues were looking through Aladin Lite, an online tool that compiles astronomical images from various telescopes.

They were searching for new black holes within our galaxy when they took a closer look at V404 Cygni, a black hole about 8,000 light-years from Earth.

V404 Cygni was one of the first confirmed black holes, identified back in 1992. It’s been studied extensively, with over 1,300 scientific papers discussing it. Yet, no one had noticed the third component in its system until now.

When Burdge examined optical images of V404 Cygni, he noticed two blobs of light close together. The first was the known black hole and its closely orbiting star.

The second blob was something else — a far-off star that hadn’t been associated with the system before.

Connecting the dots in this black hole system

To determine if the outer star was truly part of the system, the team analyzed data from Gaia, a satellite that tracks the motions of stars.

They found that the inner and outer stars moved in perfect sync over the last 10 years. The odds of this happening by chance are about one in 10 million.

“It’s almost certainly not a coincidence or accident,” Burdge says. “We’re seeing two stars that are following each other because they’re attached by this weak string of gravity. So this has to be a triple system.”

To test their ideas, Burdge ran tens of thousands of simulations. He tried different scenarios, like a supernova explosion and a direct collapse, to see how the system could have formed without losing the outer star. The results pointed strongly toward the direct collapse theory.

Old star, new tricks

The outer star is in the process of becoming a red giant, a phase that occurs late in a star’s life. This helped the team estimate that the system is about 4 billion years old.

Knowing the age gives scientists valuable insights into the lifecycle of black holes and their companions.

“Now we know V404 Cygni is part of a triple, it could have formed from direct collapse, and it formed about 4 billion years ago, thanks to this discovery,” Burdge says.

What do black hole systems matter?

To sum it all up, this discovery is turning our understanding of black holes on its head. Finding a black hole with such an unusual trio makes scientists rethink how these cosmic giants come into being.

If some black holes form quietly through direct collapse, there might be more of them out there than we ever imagined.

If direct collapse is more common than we thought, it might change how we search for and study black holes in the future. It also opens up the possibility that there are more triple systems out there waiting to be found.

The full study was published in the journal Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–