New dragonfish species reveals the fragility of the Antarctic ecosystem

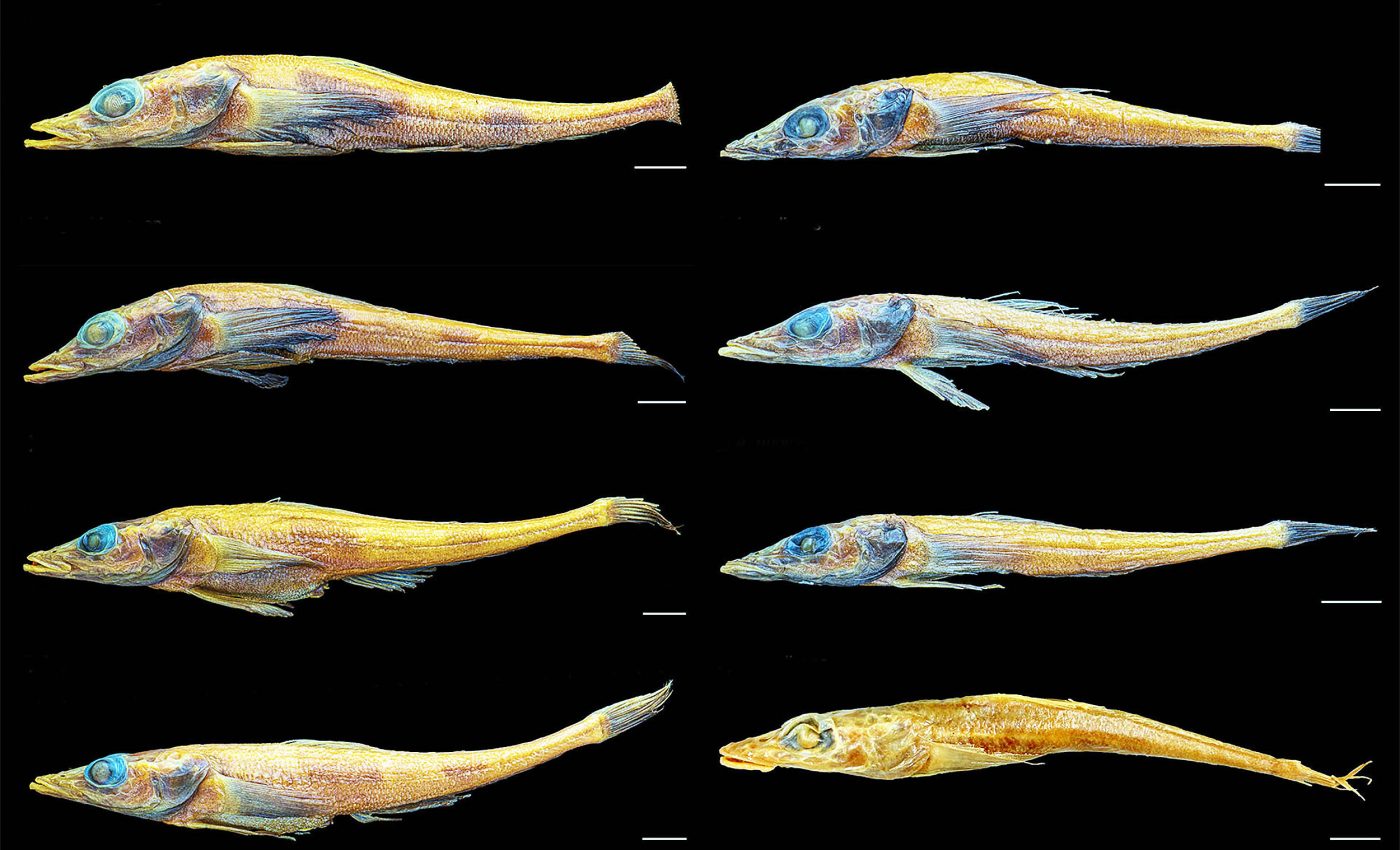

In the chilly waters off the western Antarctic Peninsula, scientists have made a thrilling discovery: a new species of Antarctic dragonfish, Akarotaxis gouldae.

The discovery of this “Banded Dragonfish” highlights both the hidden depths of biodiversity and the fragile state of the Antarctic ecosystem. The species was identified by researchers at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) at William & Mary.

Akarotaxis gouldae

The discovery of Akarotaxis gouldae began when larval specimens, initially assumed to be Akarotaxis nudiceps, were collected during zooplankton trawling missions off the Antarctic coast.

Upon comparing their DNA with Akarotaxis nudiceps specimens from collections at institutions like VIMS, Yale University, and the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in Paris, significant genetic differences became apparent.

The experts were able to confirm that these specimens belonged to a previously unrecognized species.

Study lead author Andrew Corso conducted the research during his PhD studies at VIMS under the guidance of advisors Eric Hilton and Deborah Steinberg. Corso emphasized the importance of genetic testing in modern taxonomy.

“In the world of fish taxonomy, it’s becoming common to distinguish species with genetics alone. Genetic testing is an extremely valuable tool, but our discovery highlights the importance of early life stage morphology and natural history collections like those at VIMS and other institutions,” said Corso.

Subsequent morphological analysis of adult Akarotaxis gouldae samples from ichthyology collections worldwide confirmed these genetic findings.

“There are two distinct bands on the sides of adult Akarotaxis gouldae that are not present on Akarotaxis nudiceps, so we were surprised that the species already existed in collections but had been previously overlooked,” noted Corso.

Empowering insights from genetic testing

Through time-calibrated phylogeny, Corso and his colleague Thomas Desvignes from the University of Oregon’s Institute of Neuroscience estimated that Akarotaxis gouldae diverged as a separate species approximately 780,000 years ago, when the Southern Ocean was predominantly covered in glaciers.

“We hypothesize that a population of dragonfishes may have become isolated within deep trenches under glaciers, surviving on food pushed in by the moving ice,” Corso explained.

Once the glaciers retreated, this subpopulation had become distinct enough to be reproductively incompatible with Akarotaxis nudiceps.”

Ecology of Antarctic dragonfish

Despite their crucial ecological role, much remains unknown about Antarctic dragonfish. These species, including Akarotaxis gouldae, inhabit the deep, remote waters of the Southern Ocean.

The dragonfish species exhibit unique behaviors like nest guarding in shallower coastal waters, and their offspring remain closer to the surface during the larval stage.

Examination of female dragonfish ovaries has shown limited reproductive capacity, and larval sampling suggests that Akarotaxis gouldae is confined to the waters around the western Antarctic Peninsula.

“Akarotaxis gouldae appear to have one of the smallest ranges of any fish endemic to the Southern Ocean,” said Corso.

“This limited range combined with their low reproductive capacity and the presence of early life stages in shallower waters suggest that this is a vulnerable species that could be impacted by the krill fishery.”

These dragonfish serve as a vital food source for many Antarctic species, including penguins, whose populations are already under threat from changing environmental conditions.

Akarotaxis gouldae honors a scientific legacy

The naming of Akarotaxis gouldae honors the legacy of the ARSV Laurence M. Gould, a vessel that significantly contributed to Antarctic research for over two decades.

The vessel’s decommissioning marked a shift in the U.S. Antarctic Program’s priorities, highlighting the ongoing need for support and resources to continue studying the region’s unique biodiversity.

“To me, the loss of the ARSV Laurence M. Gould marks a setback in the scientific study of the Antarctic region. Antarctica is warming faster than anywhere in the Southern Hemisphere, and there is untold biodiversity in the region that we’re only beginning to understand,” Corso concluded.

“By naming this fish after the ship, we hope to honor its scientific contributions while also bringing attention to the need for additional resources to study this unique ecosystem.”

This discovery emphasizes the urgent need to protect fragile ecosystems and the invaluable biodiversity they support.

The study is published in the journal Zootaxa.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–